Whether you are a butterfly enthusiast or bee fanatic, the Bohart Museum of Entomology just might be the place for you. About every month, the public has the opportunity to attend a bug-themed open house and observe the vast collection of insects at the museum.

Due to the demand for a December event, the museum will be holding a special weekend event from noon to 3 p.m. on Saturday Dec. 7. Additionally, the previously scheduled January “Snuggle Bugs” open house will take place as planned on Jan. 12.

Home to over seven million insect species, the museum holds one of the largest insect collections in North America.

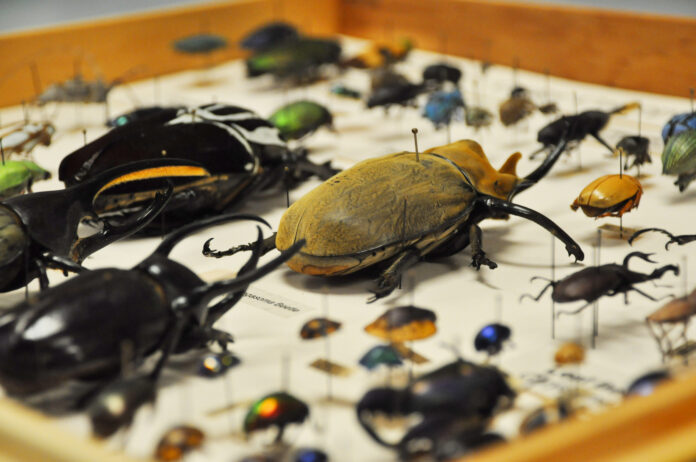

“This month we decided to focus on beetles,” Tabatha Yang, the education coordinator of the museum, said. “Beetles are the most extraordinarily diverse group and we have a really large beetle collection.”

On Nov. 23, the museum held “Beauty & Beetles,” its second open house of the academic year. Due to the massive crowds on Picnic Day, Yang decided to plan specialized open houses throughout the year.

According to Yang, typically 80 to 100 people from all over the county come to explore the museum.

“We have people coming in from Sacramento, Yuba City, Elk Grove, just to name a few,” Yang said.

Lynn Kimsey, the director of the Bohart Museum and professor of entomology has found that the weekend open houses are more accessible and less crowded in general.

“It’s hard for families to come in on weekdays,” Kimsey said. “Sometimes it’s pandemonium with 200 people coming in.”

After its founding in 1946 by UC Davis professor of entomology Richard M. Bohart, the collection gradually grew as a result of the collaborative effort of scientists, hobbyists, retired professors and graduate students.

“This [collection] is a lifetime’s work and has been built by everyone’s efforts, growing since UC Davis was established,” Yang said as she pointed to jewelry composed of beetle wings.

The jewelry included a beetle-beaded necklace and earrings that were donated by a woman who purchased the items while traveling to various locations in South America.

Once individuals donate resources to the museum, staff and volunteers meticulously organize the specimens by species, date, location and collectors.

Jeff Smith, an entomologist who worked in the pesticide control industry, has been volunteering at the museum for 26 years.

Due to his passion for insects and love of nature at a young age, Smith helps to organize and maintain the collections.

“It combines my love for bugs, neatness and organization and I enjoy helping to educate people about bugs,” Smith said.

Smith believes that education is imperative in order for the general public to truly understand the importance of insects.

“People tend to forget about bugs,” Smith said. “Or most people will just kill them — if there’s a bug in the house, kill it.”

Along with unawareness, insect endangerment and extinction is often left unrecognized as well.

Greg Kareofelas, a volunteer at the museum and open house, explained that several unique species from nations such as Ecuador and Costa Rica are slowly decreasing over the years.

“These [bugs] will come and go and no one will even notice,” Kareofelas said.

Like Smith, Kareofelas began volunteering at the museum because of his love for insects. His eyes lit up as he pulled out a case of Morpho butterflies which are predominantly located in South America.

After explaining how difficult it is to find one of these stunningly shiny, blue butterflies, a young girl asked him whether it was worth it to go to South America for the butterflies, despite the other harmful insects that are usually found in the area.

“This is worth whatever or how miserable you may be to see this in your life,” Kareofelas said. “To see one of these in the sun would blow your mind.”

Many of the volunteers and staff are clearly excited to share these insects with the public. As Yang showed a collection of dung beetles, she specified the apparent differences in size among the beetle population.

While pointing to a round, brown ball of elephant feces that was found in the Republic of South Africa in 1987, Yang talked about the way in which the beetles work to form this precise symmetry.

“It would be fairly easy for us humans to roll this dung into a round ball. But imagine a little beetle rolling around and creating this,” Yang said. “We would have a disgusting, poopy world.”

In order for scientists to study evolutionary relationships and analyze species like these dung beetles, the museum organizes everything taxonomically. Additionally, the specimens include more specific information such as collection date, location and who it was collected by.

“A collection can help you determine patterns in nature and the world,” Yang said. “Through collections, scientists can compare the specimens and observe the changes over time.”

Although Yang finds that evolution is not necessarily a nice or neat process in that it is not always easy to interpret, she believes that the museum’s lifetime of work continues to drive significant research and findings.

In addition to the abundant resources that the museum provides for ongoing projects and research, Yang intends for it to be accessible to everyone.

“Anyone can walk through our door and we will do our best to welcome them and fuel their passion or interest,” Yang said. “The museum is a mecca for people who love bugs.”