Davis community members discuss struggles they have encountered as queer Muslims

By UMAIMA EJAZ — features@theaggie.org

Content warning: This article contains discussions of homophobia and trnsphobia that some readers might find disturbing.

Disclaimer: Some sources have chosen to remain anonymous for their safety. Saeed Zaheer and Sumaira Khan are pseudonyms for these sources’ identities.

“Allah, can I please not cry once a month, when I’m not dressed as a woman?” Saeed Zaheer, a fifth-year Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior (NPB) major, said.

Zaheer, whose name has been changed, has lived as a brown cis male for 23 years. There were days when he wore khaki pants and a brown hoodie while he played his favorite instrument, a bass guitar. He said that it wasn’t until September 2021 that he recognized that there was more to his identity than he had previously thought.

Nowadays he still wears khakis and a hoodie, but on others, he wears his black midi-length cotton dress, black eyeliner and favorite sneakers. Zaheer now identifies as a bisexual, bigender Muslim — bisexual meaning that he is attracted to more than one gender and bigender meaning that he identifies as a man and a woman simultaneously.

It has only been a week since Zaheer made the decision to publicly share his identities, but he said that as a Muslim queer person, this means his problems “don’t add up — they multiply.”

Although Zaheer grew up in a Muslim household, he said that it wasn’t until college that he truly embraced the religion. He said his family has been one of his biggest support systems, especially his father, who has always instructed him in the art of humility and acceptance, which he believes Islam teaches.

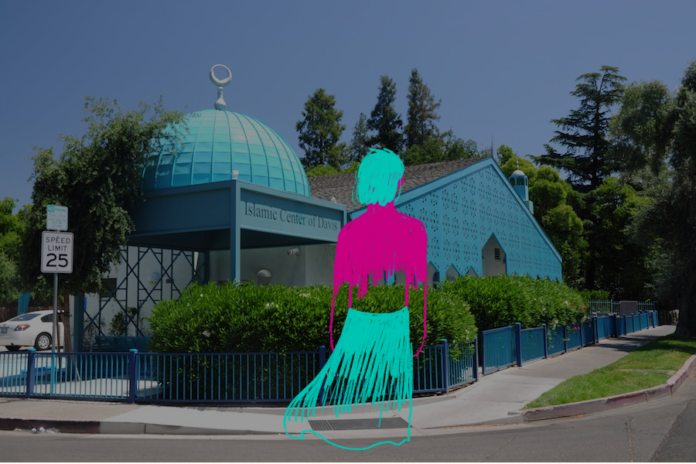

Zaheer said that he has struggled to find a place within the community — especially at the mosque — and he often does not want to go at all because he feels like he does not fit in.

“The Quran says the male is not like the female, but I’m not going to force anyone to be in those boxes,” Zaheer said. “I get tossed back and forth between these two boxes as a bigender person.”

Zaheer sees emulating his religion’s central figure, the Prophet Muhammad, as the ideal way to lead one’s life. He believes that the Prophet Muhammad would always address someone the way they wished to be addressed, as it is a Prophetic characteristic to be respectful to people, to speak to people gently and to call people what they wish to be called, especially if doing otherwise would cause them psychological distress.

“Even the Quran commands us to go observe the natural world,” Zaheer said. “There are researchers at the [American Pyschological Association (APA)] who believe biological factors such as genetic influences and prenatal hormone levels, early experiences and experiences later in adolescence or adulthood may all contribute to the development of transgender identities. The psychological evidence that this doesn’t go away is convincing.”

For Zaheer, the conflict that comes with having both of these identities has proven to be a threat to his faith, community and happiness. While Zaheer is trying to balance his life with his family’s help, he said that not all can.

Sumaira Khan, another student whose name has been changed, identifies as a bisexual second-generation Pakistani-American. She said that she spent most of her Sundays with her friends studying the Quran and eating the food her mother made in their home in Roseville. This home was far away from her roots, but she said that in these moments, she felt complete. She had found everything — her identity and community — in her hometown.

When she began to go through puberty, Khan recalls finding that she was attracted to girls, and how that changed this Sunday tradition for her.

“I still remember how and when my favorite Sundays started feeling suffocated,” Khan said. “I felt like an imposter around my friends. They would make homophobic jokes, and I would stop and think, ’Oh my God, nobody in this room knows that I’m attracted to girls,’ and I feel like if they did, they would all be very uncomfortable with the fact that I was here.”

Khan wondered if perhaps, despite her friends’ close-mindedness, her parents would accept her true self if she were to reveal it to them. But that was not the case, she said.

“I told my mom and my dad, and they freaked out,” Khan said. “Like with many other Muslim parents, it was a blame game. It’s your mom’s fault, or it’s your dad’s fault. ‘What did we do while raising you?’ After that moment, I think they’ve decided that I just never said that. They’re choosing to pretend like I didn’t say it. Every now and then, they say, ‘Thank God you’re not attracted to girls anymore.’”

Both Khan and Zaheer shared experiences of feeling that the Muslim community had generally been hostile toward the queer community.

Imam Azeez, a senior imam (leader of prayer) and cofounder of the Tarbiya Institute, an Islamic organization, has been open about his apprehension towards the LGBTQIA+ community.

According to Azeez, Islam doesn’t define people by a particular identity but teaches that God advises that there is a healthy way to live and that being queer is “not a healthy lifestyle.”

“LGBTQ is a way of life that is not conducive to happiness,” Azeez said. “Islam doesn’t require me to impose anything on them or force anything on them. Islam requires me to maintain a cordial relationship, to maintain a mutual respect.”

He nonetheless acknowledged that judging other people can indeed be harmful and emphasized the notion that everyone should be welcome at places of worship.

The Aggie reached out to the Muslim Student Association (MSA) for a comment but didn’t hear back from them.

Many young queer muslims still often feel unsafe in their communities, but some are working to improve their situations. Zaheer wants to study clinical psychology because he believes that there needs to be more people of color in the mental health field.

“Some people’s view of gender is not something that can be applied to queer Muslims,” Zaheer said. “Telling a Muslim kid struggling with their gender that ‘gender is all made up; it’s just society,’ is not going to help. There needs to be more Muslim therapists.”

Written by: Umaima Ejaz — features@theaggie.org