Janet Fulton’s nine-year legal ordeal exposes human subject research without legal compliance

When Janet Fulton, a former registered nurse at the UC Davis Medical Center, first filed a report concerning a joint research program conducted by the university, it took up to seven years for any of her concerns to be legally validated.

Fulton filed a lawsuit on Sept. 18, 2009 claiming that she had been a victim of whistleblower retaliation, which is when the University of California (UC) illegally retaliates against an employee for “blowing the whistle” on legal violations or other gross practices performed by the UC, despite being protected under the university system’s Whistleblower Protection Program.

For Fulton’s case, the backlash followed after she reported improper research practices being exercised in a study conducted by UC Davis’ Healthcare Policy and Research (HPR). For legal reasons, Fulton was unable to comment on the case but was able to provide information regarding her situation, so all questions were diverted to her lawyer.

In November 2015, the UC Board of Regents granted a $730,000 check to Fulton after a jury ruled in favor of Fulton’s case. Out of the $730,000, $330,000 was awarded for lost earnings, while the remaining $400,000 was for noneconomic damages. These damages include the social, emotional and mental consequences Fulton experienced during and after the trial.

While Fulton’s settlement was officially granted on April 23, 2014, it took a total of seven years for the settlement to be reached from the time she first filed the lawsuit.

Fulton began working for HPR in April 1998 as an administrative nurse. By 2006, she was both a part-time employee and part-time UC Davis student in the process of obtaining a postdoctorate in human development.

By December 2006, HPR assigned Fulton to be a part-time nurse researcher to the Community Oriented Pain-Management Exchange (COPE). COPE was a $5.5 million federally-funded effort sponsored by the California Department of Correction, the Correctional Medicine Network at UC San Francisco and HPR. The study’s primary interest dealt with pain management for inmates primarily held in the San Quentin State Prison.

Four months into her employment, Fulton noticed that the program had been improperly collecting prisoners’ medical histories, including their sexual history and HIV/AIDS status, without asking for their consent.

After sharing her concerns with her research manager to no avail, Fulton left COPE in June 2007. Days after leaving, Fulton anonymously reported COPE to UC Davis’ Institutional Review Board (IRB). IRB, a subsection of UC Davis’ Office of Research, was created to ensure that all UC Davis research involving human subjects align with federal, state and university policies.

Between June 12 and Sept. 10, 2007, IRB launched an in-depth investigation on COPE. On June 13, 2007 IRB ordered COPE to suspend all research until the end of the investigation. During the investigation, which included a hearing, IRB asked Fulton asked to testify against COPE, promising to grant Fulton whistleblower protection in return.

IRB discovered Fulton’s claims to be true, that COPE had been conducting research on human subjects without proper approval, going against university policy.

In response to these findings, IRB made several suspensions to COPE’s principal investigators and required further training for the rest of the research staff. IRB also urged UCSF to drop their support of COPE. Following IRB’s findings, COPE was terminated.

After COPE’s disbandment, Fulton began to notice instances of whistleblower retaliation. On a personal level, Fulton’s former husband Ken Keyzer was fired from his position as an IT analyst under COPE. After filing an internal grievance, UC Davis offered Fulton the position “Analyst VII” under the Battelle Memorial Institute. According to Fulton, this project-based position was a demotion from her former jobs, and was planned to end within 30 to 80 days.

In an attempt to compensate for the demotion, Fulton was later informed that the position would be granted to her with no need to apply. Fulton had turned down the position and was terminated from UC Davis in December 2007.

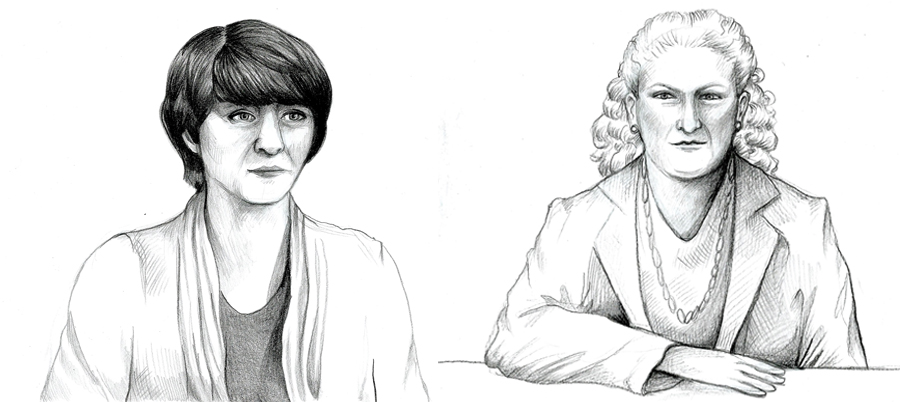

The university’s failure to offer a similar position to Fulton led her to file a lawsuit against the UC Board of Regents. Represented by attorney Mary-Alice Coleman, Fulton claimed that the university had retaliated against her on the basis of her whistleblowing.

Between 2009 to 2014, Fulton had to oppose six counts and file four motions. According to Coleman, she was unable to represent Fulton because the UC claimed that Coleman was a witness. Second, the Regents failed to supply 1600 pages of court-ordered legal documents until days before the trial. Known as a “document dump,” this tactic would make it difficult for Coleman and Fulton to build a stronger case against the Regents by holding critical evidence.

During the trial, the Regents claimed that there was no form of retaliation present because they had given her the same benefits as her previous employment. Additionally, the Regents invited two key witnesses to testify, Dr. Klea Bertakis and Dr. Patrick Romano, both who claimed that COPE was not a human research project and did not need approval from the IRB.

According to Chapter 240 of UC Davis’ Policy and Procedure Manual, “human subjects research” is defined as “any research project that obtains data about the subjects of the research through intervention or interaction with them; identifiable private information about the subjects of the research; or the informed consent of human subjects for the research.”

For Fulton, the act of collecting medical records was a form of collecting prisoners’ private information. Thus, Fulton believed that COPE was technically conducting an experiment using human research and did need approval.

Fulton and her legal team discovered several documents, including an e-mail published by the Davis Vanguard, that supported Fulton’s claims of whistleblower retaliation.

“I think it will be best to put [Janet] back to work, then lay her off in the usual manner, rather than under the current peculiar [and perhaps questionable] circumstances,” Romero said in the e-mail.

With a 9-3 vote, the jury determined the UC Regents’ argument to be lacking sufficient evidence, validating Fulton’s claims that she was a victim of whistleblower retaliation.

“The University of California investigates all claims of violations of laws and policies thoroughly, and that was true in this case as well,” said Andy Fell, associate director of news and media at UC Davis. “The university took time to review carefully its options in this matter as well as its internal complaint procedures.”

Fulton’s failure to be protected under UC’s Whistleblower Protection Program, prompted the attention of former California Senator Leland Yee. Yee’s Senate Bill 219, which passed in February 2009, would revise California’s existing Whistleblower Protection Law so that it offered the same level of protections for UC employees as it did to other federal employees. In a quote published by the Davis Vanguard, Chief Justice Kathryn Mickle Werdegar emphasized the bill’s importance.

“The court’s reading of the act, making the university the judge of its own civil liability and leaving its employees vulnerable to retaliation for reporting abuses, thwarts the demonstrated legislative intent to protect those employees and thereby encourage candid reporting,” Werdegar said. “If the same government organization that has tried to silence the reporting employee also sits in final judgment of the employee’s retaliation claim, the law’s protection against retaliation is illusory.”

For Coleman, Fulton’s story should not be representative of the university’s nature, because every system is imperfect and legal representation needs to be in place for those who want to help correct issues within the system.

“Most people do [follow the rules]. Most people try [to follow the rules] and the system tries to steer right,” Coleman said. “But It is important for people to feel enough integrity and internal fortitude to be able to push it back when it starts getting out of line.”

Written by: KATRINA MANRIQUE – campus@theaggie.org