A recent study lead by scientists at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory reveals the seriousness of climate change and its impacts

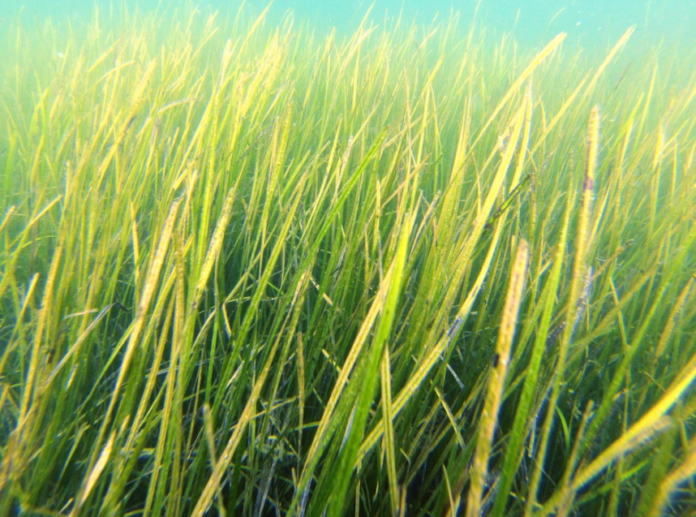

A UC Davis study has provided evidence that seagrass meadows can do more than create homes for active ecosystems; they can buffer ocean acidification. The study, led by Aurora Ricart, included seven seagrass meadows from approximately 1000 km of the U.S. West Coast over a time period of six years.

Ricart, the lead author of the paper published in the journal Global Change Biology, was involved in the project when she was a postdoctoral scholar at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory. Ricart is currently working at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences located in East Boothbay, Maine.

The driving force for Ricart and other researchers was to find a solution for reducing ocean acidification, a phenomenon caused by anthropogenic effects. Since climate change is happening now and will continue to worsen, the best thing to do is slow it down and mitigate its effects, according to Ricart.

The study was started by UC Davis researchers including Tessa Hill, a UC Davis professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. When it was proposed that seagrasses were a way to buffer ocean acidification, Hill and other researchers collected part of the data and tested the methodology. Ricart was recruited three years later in 2017 to analyze and interpret the data because of her expertise in seagrass ecology.

The main implications of the study focus on management and policy, according to Ricart.

“I really hope this work opens the door to ask questions on conservation and restoration on seagrass ecosystems and natural ecosystems that can really help us to deal with climate change effects,” Ricart said.

This is the largest study done on seagrass meadows, according to Hill. Researchers documented the seagrass’ ability to modify the local environment and noticed that over time, ocean acidification around these beds had significantly been reduced.

“It has the power of millions of data points that show these trends that seagrass beds improve the environment within and around them when it comes to carbon and climate change,” Hill said.

Now, the state of California and conservation groups that are interested in protecting seagrass meadows have even more evidence that these areas need to be preserved. Prior to the study, most evidence that seagrass benefited its local ecosystem centered around how the plant provides a good habitat for young organisms, such as dungeness crab, and acts as a filter to remove pollutants. Through this study, it has been determined that seagrass removes carbon dioxide from the water through photosynthesis and protects the aquatic community from ocean acidification, according to Hill.

Melissa Ward, a UC Davis graduate student researcher at the time of the study and currently a postdoctoral researcher at San Diego State University, assisted in the field operations of the project. This consisted of preparing the equipment, gathering a team of divers, coordinating with whoever was at the site and showing up with all the equipment. It also included deploying water chemistry sensors into the seagrass meadow and pulling them out, driving back to the lab, cleaning them up and pulling the data from the sensors, according to Ward.

The deployment process of the sensors was about a month long. This meant several weeks of preparation at the lab to prime the sensors and get them ready.

“[The sensors] are the most needy pieces of equipment. I felt like I was babysitting,” Ward said.

The sensors had to get accustomed to the seawater they were going to be in and were put in tanks while being transported to keep them wet on the way to the field site. Float-bags were attached to the heavy sensors so the divers would have an easier time placing them in the seagrass meadow. Divers would deflate the bag to lower the sensors carefully into the water. The sensors are held by anchors screwed to the sediment of the seafloor.

“The whole process was exhausting but super fun,” Ward said.

Priya Shukla, a Ph.D. candidate at UC Davis, participated in the study when she was a lab manager for the Bodega Ocean Acidification Research Group. Along with being a co-author on the published paper, Shukla helped collect water samples and processed them to get an accurate reading of seawater chemistry.

“The two things I was specifically doing was measuring pH and alkalinity,” Shukla said.

Shukla was interested in how the presence of seagrass beds in the proximity of oyster farms and reefs could actually help the oysters build their shells. Restoring the seagrass beds and other ocean ecosystems could have strong benefits for coastal communities and economies, according to Shukla.

“Restoring ocean ecosystems isn’t just a conservation goal; it could actually be a humanitarian goal because it can make a difference for humans across the planet because the ocean certainly has a strong role in the planetary climate,” Shukla said.

Written by: Francheska Torres —science@theaggie.org