Emerald Fennell’s debut feature disappoints

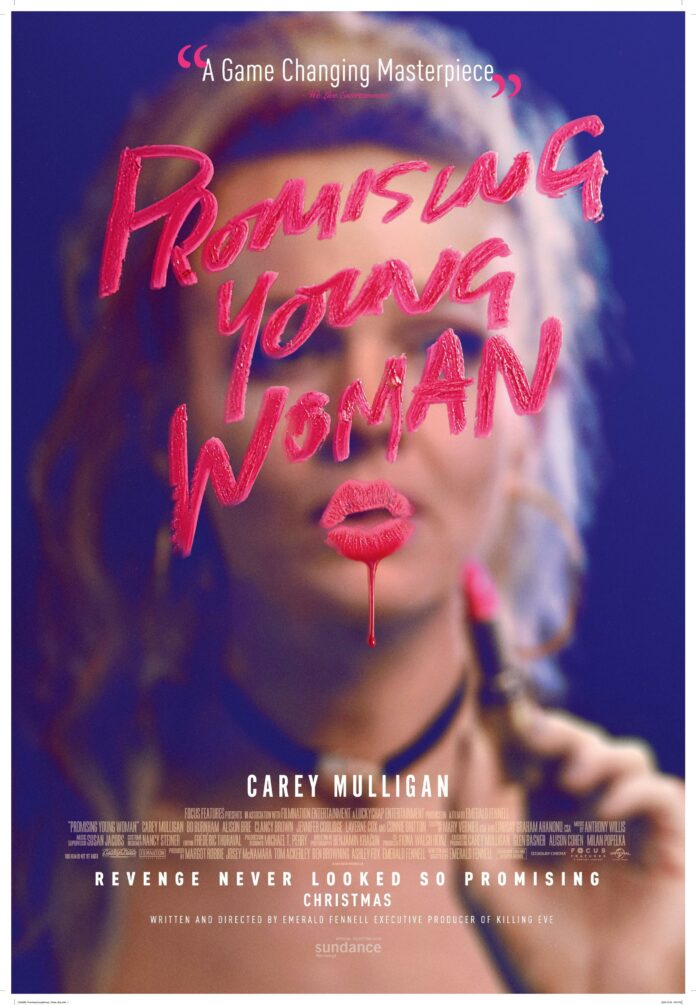

“Promising Young Woman” came out on Jan. 25, 2020—more than a year ago. In that time, it’s earned at least $15.2 million and sits at a cool 90% on Rotten Tomatoes, which as the website says, denotes “universal acclaim.”

Is $15.2 million a lot of money? For an indie film, absolutely. For a blockbuster, absolutely not. But with a budget reported to be under $10 million, the film probably broke even at least. When we put all these facts together, it would appear that “Promising Young Woman” was a completely reasonable success across the board, especially when you take into account that the film came out in one of the worst years for the film industry in the last century, missing the formal beginnings of lockdown in America by a few short weeks.

What I’m saying is that the average viewer would have no reason to think “Promising Young Woman” to be anything but a modern, competent, revenge thriller—respite from the flashy corporate repetition of superhero movies, maybe even something with some art in it. This is a tall order to ask of American film, especially since the 2008 recession, which shook the industry to its core and all but killed the gambler’s spirit in financiers that had driven occasional innovation since the dawn of the motion picture.

So many movies today have what might be called “USC Gloss”—a spirit of smooth, flowchart-like polish that feels more like an alien’s imitation of a movie than anything originating in an artistic process. The “USC” part of that term originated in the rich-kid fueled film programs at universities across the nation, whose task appears to be to pump out as many coddled trust-fund alumni as possible. This saturates the industry with people who have the unconditional monetary support necessary to pursue a career as risky as filmmaking, but have no original thought or life experience beyond getting blackout drunk at frat parties five times a week and watching every David Lynch movie.

So then, knowing that director (and “Killing Eve” showrunner) Emerald Fennell read English at Oxford before becoming a highly successful actress straight out of school, that all her characters are higher educated, stressless psychopaths with unexplained and seemingly unlimited pools of money, that such a thing is not just, in her eyes, the base state of the world—one in which everyone is a handsome, studious medical school graduate—but it is so unquestionably that it doesn’t even need to be acknowledged, does “Promising Young Woman” have said gloss?

With a film that attempts to examine a certain type of real-world evil so common and despicable as to be ubiquitous among its characters yet simultaneously appears to be ignorant of its (apparently class-based) biases, it’s only a matter of time until the viewer begins to question Fennell’s authority and dissociate from her cruel, sterile world of affluent adult-babies.

The core of “Promising Young Woman” is, unfortunately, allegorical. Details of character and visual experience are afterthoughts, conduits designed to aid the spread of a moral message, and as a result have no life of their own. Characters who repeat stock dialogue suddenly burst into the perspective and arguments of the writer, and the stylish, neon pop crust surrounding the movie—complete with gratuitous chapter title cards—is unmistakably purposeless. It feels like a fake movie, like someone has copied down the practices of popular modern filmmakers without examining the why of each, and used them to construct a shabby shell around an existent point that really, really should have just been an essay.

What is gained by making a didactic, sermonizing movie like this? If the characters don’t matter and the filmmaking doesn’t matter, why should this exist at all? The answer appears to be that Fennell made this film for the express purpose of teaching the audience. There’s no room for exploration or examination of the central ideas, and nobody learns anything by the time the credits roll—it’s about getting one brief idea from the director’s head into the world. There is no love for the process of making movies here and apparently no value in any of its possibilities beyond the most utilitarian and cynical. All of this is meant to say that “Promising Young Woman” is, on some level, insulting. Using film as a stepping-stone to such a simple and inappropriate goal tramples the potential inherent to the medium—an unthinkable opportunity cost.

Quentin Tarantino, who American filmmakers (including Fennell, if this movie is anything to go by) worship today perhaps more than when he was at his peak, was a high school dropout who worked at a video store for half a decade. As cartoonish and hokey as his movies are, Tarantino is not ignorant of the world he lives in. His decision to retreat into the universe of exploitation films and Fellini and the French New Wave is an informed one. It’s difficult to say the same of Fennell.

“Promising Young Woman” won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay this year. Is this really it? The best screenwriting that we have to offer? An experiment in sheep-herding in which the director had to create “mood boards” mid-production to establish that her protagonist had depth because the script didn’t? If so, maybe we should just call it here, wrap it up. End of the show, folks, go home.

One of the most bizarre things I’ve heard people say about “Promising Young Woman” is that because it addresses such a horrible, so-often-ignored issue in society, it shouldn’t be treated the same as other films. To which the most reasonable response is: wouldn’t such a terrible thing be best handled by, like, a good movie? Carey Mulligan puts forth noticeable talent in her performance, teasing emotion out of a protagonist that seems to have none, and the events come one after another in a sensible enough way, but none of it is enough to recover anything from the film’s shallow conceit. Everyone, but especially those who have actually suffered, deserve something better.

Written by: Jacob Anderson — arts@theaggie.org