Pathogens can attach to microplastics and affect sea life

By MONICA MANMADKAR — science@theaggie.org

Microplastics can carry pathogens from land to sea, which can affect wildlife and overall human health, according to a study conducted by UC Davis researchers. Published in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers found that microplastics make it easier for disease-causing pathogens to cluster around plastic-filled areas of the ocean and impact wildlife.

In a previous study, the team had investigated how land-based pathogens can enter the marine food web through natural oceanographic processes such as marine snow and biofilm entrapment. However, with an increase in attention and research devoted to plastic pollution in the environment, researchers started asking themselves whether similar processes of ‘trapping’ pathogens can occur through these man-made pollutants.

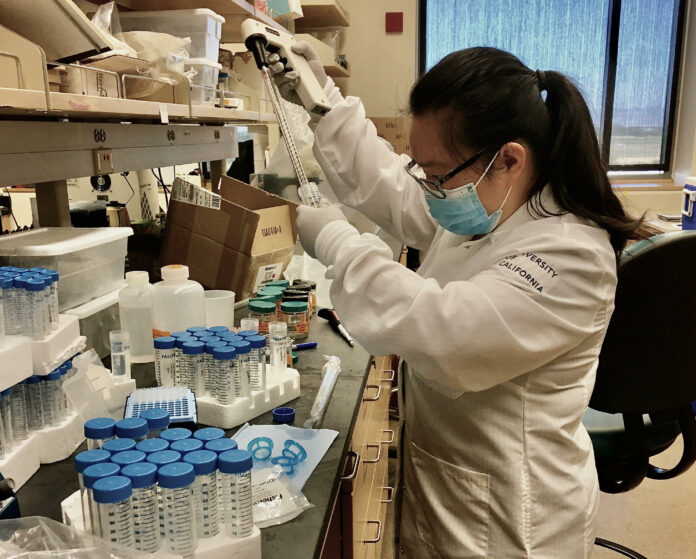

“Once they reach different water bodies, plastics start forming a sticky biofilm layer just like many other materials in the sea, and we were interested in figuring out whether there could be some interaction between these two different types of pollutants: pathogens and plastics that both end up in the coastal ocean,” said Emma Zhang, a doctoral candidate at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, via email.

There have been very few studies investigating the interaction between pathogens and plastics. The researchers investigated zoonotic protozoan pathogens that are widespread and have variable effects on human health and animals. Examples include Giardia and Crypto, which cause gastrointestinal disease such as diarrhea and can prove deadly in very young children as well as those who are immunocompromised. The parasite Toxoplasma mostly causes asymptomatic infections in animals and people but can also be deadly for certain groups.

“We are specifically concerned about pregnant women who become exposed for the first time to Toxo, where the parasite can infect the developing baby and cause miscarriage, abortions, or life long illness (if the baby survives) with a disease called congenital toxoplasmosis,” Zhang said.

The main driver of these issues is plastic pollution, which is caused by society’s dependence on everyday products made from synthetic polymers that do not readily degrade in the environment. These polymers include synthetic textiles like polyester clothing and cosmetics containing microbeads. The researchers also considered the industrial use of plastics and the use of fishing nets throughout the ocean, which eventually break down into microfibers.

“There is no one solution, rather we really need an integrated approach that shapes policy and human decision making to help reduce our dependence on plastic products and their eventual pollution in aquatic systems,” said Dr. Karen Shapiro, a professor in the department of pathology, microbiology and immunology at the school of veterinary medicine, via email. “Everyday actions that we all should and can take are reducing or even better eliminating use of single-use plastics (plastic bags, disposable plastic dishes, etc.), choosing natural fiber clothing when possible, line drying clothings instead of using the dryer (which release plastic fibers from our synthetic clothes) and also integrating use of microfiber filters on washers and dryers at home.”

Shapiro noted that their results showed for the first time that land-derived zoonotic pathogens, germs that can infect both animals and people, can stick to the surfaces of plastics that end up in the sea.

This association between pathogens and microplastics could impact disease transmission in two important ways. One, shellfish can ingest plastics and any particles that hitchhike along, including parasites. Two, researchers now know that plastics can disperse very far from the original source of pollution.

Plastics can reach the deep ocean and remote locations far from where humans live, including arctic regions. Zhang said that their findings imply that microplastics may act as important mechanisms for pathogen transport in the ocean.

On the other hand, microplastics that sink may concentrate these pathogens in the benthos where filter feeding marine invertebrates such as oysters, clams and other shellfish live, thereby increasing the likelihood of their ingestion and leading to the contamination of marine food webs.

Looking to future work, Zhang and the other researchers would like to perform experiments in live oysters to determine if they are able to become infected with these pathogens when placed in seawater contaminated with microplastics that have pathogens associated on their surfaces.

However, in general, Zhang asserted that their study highlights the importance of the One Health approach, which recognizes that the health of humans, animals, plants and the shared environment are deeply connected. Collaboration across human, animal and environmental disciplines will be required to address a challenging problem affecting the shared marine environment, as everyone is dependent on the ocean.

Written by: Monica Manmadkar — science@theaggie.org