Incoming assistant professor at UC Davis, Brenna Mockler, shares insights on her research on supermassive black holes

By EKATERINA MEDVEDEVA — science@theaggie.org

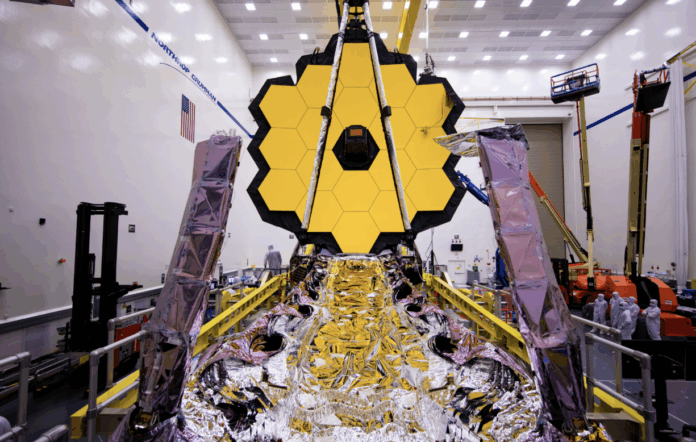

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) set out on its cosmic voyage on Dec. 25, 2021. The JWST is the largest and most powerful telescope built to date, featuring enhanced infrared vision that enables us to pierce through clouds of gas and interstellar dust to observe some of the first stars and galaxies that appeared after the Big Bang. The result is some of the most awe-inspiring and high-resolution photographs of the cosmos, including a very famous image of the Carina Nebula released by NASA in July 2022. However, just six months later, astronomers’ interest was piqued by a much subtler, but nevertheless mind-boggling detail that appeared in multiple JWST images of the early universe — little red dots (LRDs).

These very bright and extremely compact objects, which existed mostly during the first 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, feature characteristics that put them outside of known categories of celestial bodies; objects like these were never observed by other telescopes at lower redshifts (i.e., closer to our time).

The first two main theories that emerged attempted to explain their nature via extreme cases of processes that we are familiar with: one identifying LRDs with rapidly star-forming galaxies and the other with rapidly growing supermassive black holes (SMBHs).

“Since LRDs appear highly compact for how bright they are, it was first thought that they could be very, very rapidly star-forming galaxies with a lot of stellar mass in a very small volume,” CTAC Postdoctoral Fellow at Carnegie Observatories, Brenna Mockler said. “One indicator of this that people looked for and thought to have identified in some LRDs is the ‘Balmer break’, which is a drop in brightness on the spectrum associated with young stars that happens at the wavelength of around 3600 angstroms.”

Another problem with this theory is that it implies that these galaxies somehow grew extremely fast to very large scales, which is incompatible with what previous theories suggested about the mass budget available for star formation in the early universe.

Currently, a majority of astronomers lean towards the theory that LRDs are accreting SMBHs. In a recent analysis, “about 70% of the targets showed evidence for gas rapidly orbiting 2 million miles per hour (1,000 kilometers per second) — a sign of an accretion disk around a supermassive black hole,” according to a NASA article on this topic.

However, this theory does have its shortcomings. One of them is that LRDs have not been observed to have intense brightness in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, which is highly common in accreting black holes. While it may be due to a lack of information about the effect that extreme amounts of mass piled up on black holes produce, if further observations detect this high-energy emission, or the presence of jets, it could confirm that at least some LRDs are SMBHs. A discovery of gravitationally-lensed LRDs would be very useful, as it would allow observations with higher spatial resolution to put tighter constraints on the size of LRDs.

“We don’t really understand how the black holes that we see today got so large, especially the SMBHs that are at the centers of galaxies [also known as Active Galactic Nuclei (AGNs)],” Mockler said. “Even if you feed a stellar mass black hole formed by a supernova at what we think is its maximum accretion rate over the entire course of the universe, it still wouldn’t grow to the size of the largest black holes that we see today. One of the things that would help is if there were very rapid accretion episodes in the early universe to start building these black holes up at early times — people are excited about this theory because it has the potential to bridge the gap in black hole evolution.”

Mockler, who is part of the department of physics and astronomy, conducted most of her research on tidal disruption events (TDEs) — processes in which stars get eaten by black holes, producing massive amounts of energy. These events evolve in the matter of days and months, making them observable on a human timescale unlike many processes in space.

“I developed a model, a while ago now, for connecting the light curve evolution time scale to the black hole mass,” Mockler said. “The black holes that we notice involved in TDEs generally tend to be ones that didn’t have previously accreting gas around them, so they didn’t emit any light for us to be able to constrain their properties. But, when they do accrete a star, all of a sudden they light up and we can actually learn something about them, [for example] the mass of the system [they are in].”

Recently, Mockler has been involved in work concerning galaxy mergers, which open the possibility for the merging of the black holes in the center of those galaxies and result in gravitational waves that can be detected by the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) and later studied to better understand how galaxies evolved.

“Going forward, one of the exciting things about both LRDs and TDEs is if LRDs are accreting black holes, then what we’re seeing is black holes accreting near or above the Eddington limit, which is the point where the radiation pressure from the material that’s falling in gets so strong that it balances the gravitational pull into the black hole, so nothing more would be able to accrete,” Mockler said. “However, if you have jets, for example, so the geometry isn’t fully spherical, you certainly can break it. But how easy it is to break this limit is really important for understanding how quickly black holes are able to grow. TDEs regularly feed black holes above their Eddington limits. And LRDs, if they’re accreting black holes, are also probably near or above their Eddington limits. So it’s this particularly extreme regime that helps us understand the limits of black hole accretion.”

As new theories on LRDs such as black hole stars emerge, these mysterious celestial objects remain a well of potential knowledge about how our universe came to be.

Written by: Ekaterina Medvedeva — science@theaggie.org