The latest Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum exhibition considers the importance of connections across time, space and species

By JULIE HUANG — arts@theaggie.org

Open from Aug. 7 to Nov. 29, “Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice” is one of two exhibitions available to the public at the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum this fall quarter. The project originated as a traveling exhibition that was guest-curated by conceptual artist Glenn Kaino and independent curator Mika Yoshitake at UCLA’s Hammer Museum. The Manetti Shrem is its last stop.

Kaino and Yoshitake first began to conceptualize this exhibition in February 2020, gaining new clarity on the message of their work with the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased awareness of police brutality amid the Black Lives Matter movement.

Manetti Shrem Curatorial Assistant Grace Xiao explained that the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement left foundational and lasting influences on the show’s intended themes.

“They remind us that breath is precarious,” Xiao said. “The curators were really gesturing towards the idea that because of its precariousness, breath can be a point of resistance. Breath is survival, and survival for marginalized communities is resistance in and of itself.”

The theme of environmental consciousness permeates the gallery, also taking the form of a collection of paintings by Brandon Ballengée, an artist, educator and biology professor based in Louisiana. These works depict fish in the Gulf of Mexico, which have recently disappeared — likely due to oil spills in the area.

“These Ballengée works have been a student and staff favorite,” Xiao said. “The five paintings displayed are all made from oil that came from oil spills.”

Ballengée’s unconventional usage of this material, which is typically considered harmful, to create delicate artwork, highlights the often-ignored reality that the adverse effects of human activity on vulnerable environments like the Gulf of Mexico are regrettable, but not inevitable: that the negative relationship between people and the environment can be changed.

Another series of works, by Cannupa Hanska Luger, an enrolled member of the three affiliated tribes of Fort Berthold who is of Lakota descent, further examines the necessity of responding to climate change in ways that break away from prevailing attitudes. One such attitude is anthropocentrism, or the idea that everything in the world exists in relation to human beings. Through this worldview, natural landscapes and other living things are defined and valued only by how well they serve as resources to further human goals.

Combating this human-centric view of nature, Luger’s works, and “Breath(e)” as a whole, present an anti-anthropocentric and non-Western view of the world. Sculptures of people in futuristic suits, which are a part of Luger’s “Sovereign Series,” are made of a variety of materials including ceramic, steel, felt paper, cork, wood, synthetic hair, glass and detritus.

“Anti-anthropocentrism is about what happens when we understand other things around us as sovereign,” Xiao said. “Cannupa’s work imagines the land as sovereign. For example, the boots [of these statues] are made up of clay from the local area. He’s really thinking about how all these things around us are sovereign.”

Like Ballengée’s fish, Luger incorporates a range of materials into his work that are not always associated with art in the public imagination. Another piece of his on display, titled “Red Rover,” refashions outdoor furniture and discarded materials, granting them new purpose in the form of artwork.

“[Luger] is thinking a lot about Indigenous futurity, which is the idea that there are a lot of indigenous knowledge structures that we can learn from, in order to better face the climate changes that we have today,” Xiao said. “Indigenous peoples had been living on this land rather sustainably for centuries before settler-colonialism came into the country.”

Luger’s work centers the perspective that in nature, there is a place for everything. Rooted in Indigenous American culture, this view reveals that humanity’s environmental future might be preserved through connections to the past.

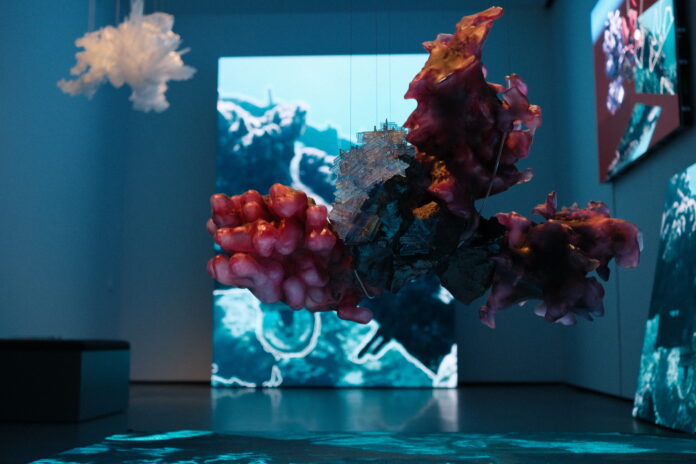

The anti-anthropocentric perspective that is diffused throughout the gallery space takes on a unique manifestation in Michael Joo’s 3D-printed coral sculptures and “Noospheres (Composition OG:CR),” a multichannel live AI-edited video installation.

“Michael is thinking a lot about how we might use AI to help the environment, and how artificial coral structures might benefit marine life if scientists find a way to use them appropriately,” Xiao said.

Acknowledging the controversial, culturally-charged reputation of artificial intelligence (AI), Xiao noted that learning of the AI-usage in the making of Joo’s piece can evoke emotional reactions in visitors, which ultimately become a part of their viewing experience.

“I approached the piece by sitting with my frustration, and it helped me discover more about the work,” Xiao said.

Occasionally, text appears at the bottom of the display screens, based on a conversation that Michael had with his collaborators — including scientists, programmers and engineers — about the concept of flux.

“He ran it through AI and it morphed the text a bit, so now the language occasionally makes sense and occasionally is garbled,” Xiao said. “The usage of AI, even if unintentionally, helps reflect the ways that language morphs over time.”

The centrality of time in “Breath(e)” continues in Jin-me Yoon’s “Turning Time (Pacific Flyways),” an 18-channel video installation filmed at a bird sanctuary on Vancouver Island, Canada. It features a group of dancers, all Korean-Canadian young adults, performing a traditional Korean crane dance.

Yoon coined the term “vertical time” to describe her work, referring to the ways that the future and the past are represented in the present moment.

“ I really love that description, which I think underlies a lot of the work in ‘Breath(e),’” Xiao said. “The Korean dance is about longevity, and this piece feels like it’s honoring what came before and what’s coming in the future.”

Yoon’s installation reflects a greater theme threading together the collection of works displayed in the “Breath(e)” exhibit center: the connections that can be made across the boundaries of space and time.

“Each of these artists are thinking about this idea that, in order to face climate change, we have to come together globally,” Xiao said. “Even though it began with something that could be called tragic, this is more of a hopeful show than anything.”

The exhibition suggests that dominant notions of what constitutes culture and appropriate reactions to cultural issues must be re-evaluated. “Breath(e)” challenges what true growth looks like, as humans might have to consider resources and perspectives that were previously dismissed in order to reach an uncertain future.

The Manetti Shrem is committed to supporting the community-building themes displayed in “Breath(e)” with its own hands-on events. One of these programs is “Art Spark,” a weekly activity that invites the community to make their own artwork related to the exhibits currently on view.

Linda Alvarez, the Manetti Shrem’s coordinator for programs and student connection, explained that there have been three different free weekend art activities centered around the “Breath(e)” exhibition, including a bee-themed sculpture in the vein of Garnett Puett’s “Apisculpture Studies” and a gel plate printing activity inspired by Ballengée’s research with fish species.

“Art Spark serves a wide audience range, and you have elementary-age kids, college-age students and elders all processing information from the show and making their own connections,” Alvarez said.

Manetti Shrem’s Academic Liaison Qianjin Montoya stated that “Breath(e)” also inspired a course taught by Professor Margaret Kemp, titled “Major Voices in Black World Literature.”

“It’s an embodied experience, as students respond not only to texts in the form of books but also artwork and images,” Montoya said. “What Margaret is doing is aligning Black storytelling with non-Western narratives that don’t always follow a linear structure.”

Montoya finds that this unconventional approach to art also resonates with the central themes of “Breath(e),” as individual artist experiences come together to form a message of environmental consciousness and social justice, not the other way around.

“Almost every artist in ‘Breath(e)’ is making artwork in response to their work with another community, whether it be a community of bees or a community in Flint, Michigan,” Montoya said. “All of them are building bridges to wider issues like climate change and social justice through personal connections to another community.”

Xiao noted that visitors have been spending more time than usual in the gallery space that constitutes “Breath(e),” which she hopes reflects the strength of interests that visitors are able to form with the artwork.

“I feel like there’s something for everyone in this show,” Xiao said. “One of my colleagues told me that she has a friend who never goes to museums, but this time he went and saw the Tiffany Chung piece. He loved it, because he’s a data scientist.”

Montoya said that the variety of mediums and forms represented by the pieces in “Breath(e)” allows its message to resonate with a wide variety of people who might think in different ways, but are each connected by shared communities, global problems and ultimately, the act of breathing.

“These urgent situations and issues that we’re dealing with can’t be communicated on a single register,” Montoya said. “They need to come through multiple registers, whether that looks like data, visual art or dance.”

Xiao characterized her own experience with the gallery space of “Breath(e)” as one of slow contemplation, reflecting on how that experience slots into the weight of its message.

“Topics like climate change and social justice have an urgency to them,” Xiao said. “There’s this idea that we always have to think about the solution, but in this exhibition, I resonated with this idea of slowing down and taking the time to stand in front of a work of art and absorb it. What can we learn from our ancestors? What can we learn from the people who have stewarded this land for centuries?”

Written by: Julie Huang — arts@theaggie.org