Algorithmic playlists mark a further evolution of art as a commodity

By THEO KAYSER — tfkayser@ucdavis.edu

When you open your phone in the year 2025, you instantly become the subject of a competition between every possible website, app and advertiser, all of whom are fighting tooth-and-nail for your attention.

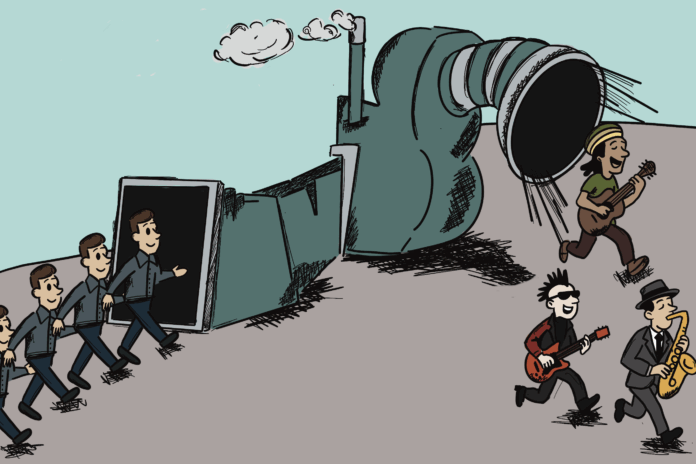

Unsurprisingly, this pattern applies to online musical consumption too. If you’ve spent any time perusing your music streaming platform of choice in the last several years, you’ve likely been suggested algorithmically-made playlists. Upon opening the homescreen of said app, you will likely be berated with playlists tailored to specific genres, such as “Indie Rock mix” or “Intimate Indie Rock mix.” This style of musical marketing is the newest strategy in a long history of evolving methods of musical consumption.

Music being commodified and sold is by no means a new tactic in our hyper-consumerist society. Historically, operas (Victorian England’s trendiest genre) were presented in extravagant theaters, the owners of which profited off tickets sold to allow entrance to the show.

In more recent memory, the discovery of vinyl pressing marked a huge change of the tide in musical consumption, allowing a much larger group of music fans to privately consume music. Decades later, the invention of the radio made music even simpler to consume.

The next landmark moment came with the Internet, which not only brought easily downloadable MP3s, but also online spaces to find new music without needing to go to the store to dig through physical media or having it fed to you by a DJ.

This brings us to 2025, where algorithms create seemingly endless collections of songs grouped together by genre tags, in conjunction with individual users’ listening habits.

The way I see it, the two apparent throughline trends in this evolution are convenience of consumption and the increased commodification of artists themselves.

Seeing as the primary goal of market-driven competition — in the music industry as well as all other private industries — is to maximize profits, record labels and streaming platforms are in a constant state of evolution to create the most appealing (or addictive) method of consumption.

Streaming in general is, in and of itself, a manifestation of this goal. After all, it’s much simpler to tap your phone a few times to access your favorite songs than it is to fiddle with the radio or handle physical media. Algorithm-based playlists are a microcosm of the same phenomenon; they further simplify the objective of finding music, as consumers no longer need to search up individual artists or albums to listen that way or to curate their own playlists. And while this all sounds great in theory — humans do enjoy convenience — it’s relevant to ask ourselves what we as listeners might lose in the process.

The act of putting intention and care behind the art you choose to consume forces you to, even if just slightly, make a personal connection with that piece of art. Consider the difference in how it feels to watch music performed live or choosing to buy a physical record, versus an algorithm quickly selecting a playlist based on what sounds might compliment your mood at that moment — the former encourages us to engage with each piece of music in a more focused and rewarding manner.

These curated playlists also depersonalize the artists themselves. Algorithm-based playlists are by no means the first attempt by record labels to put artists into a box; the use of genres to label artists as one thing or another has existed since the era of record stores and genre-associated stations on the radio. However, the way that playlists lump artists together is distinct in how flippantly they do so.

In record stores, individual albums were grouped together with those thought to be of a similar sound. However, the sale of a record still encouraged listeners to engage with the work as a whole, which often featured songs of very different genre influences, exposing listeners to a variety of sounds. In a playlist, which is often treated like one long album (and presented using the same interface), artists and songs are grouped together based on a surface level comparison of vibe or sound.

To illustrate this, consider that an “alternative rock mix” may present a song by Imagine Dragons along with a song by Nirvana. These two bands certainly share things in common: instrumentals composed of electric guitar, bass and drums, with loud vocals and lyrics. But using these criteria to create playlists reduces each artist’s individual expression to its most superficial collection of descriptors — a dystopian way to consider art. In other words, individuality — through lyrical content or sonic innovation — is at risk of being marginalized in favor of a fixation on characteristics that can be used to package and label art as just another item to be purchased off the shelf.

It is important to consider how this trains us to consume music. If our inhuman curators are grouping music together based on the vibe or genre it’s rigidly placed into, are we as consumers then influenced to consider music using that same shallow criteria ourselves? This method of consumption may deepen existing habits of engaging with art that are both superficial and arbitrary.

Written by: Theo Kayser — tfkayser@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.