How foreigners interpret the friendliness that Americans show strangers

Pierre Noro, a French international student, felt like an idiot. He must accidently have given the girl the wrong number. A week had gone by, and she still hadn’t called him.

He had met the dark-haired American girl in front of Dutton Hall which she was drawing for a landscape architecture course. He gave her some advice, and they ended up talking for three hours. When they parted, the girl asked for his number.

Pierre worried she thought he was one of those persons who just gives a fake number in order to escape further action and decided to find her contact information through the university directory.

“I only knew her first name so I bothered a few people with my emails before I found the right person,” Noro says. “We texted, and I asked her if she wanted to go out for a drink. There was an awkward text silence – the amount of time where you know it is impossible that the person has not checked her phone – and in the end she texted me and said she wanted to be my friend.”

Friendliness v. the intention to be friends

Like many other international students, Noro had encountered a friendly American who at the end of the conversation asked for his number; and like many other international students, Noro was surprised to learn that Americans don’t expect a conversation with a stranger to lead anywhere – that Americans ask for strangers’ numbers without the intention of contacting them.

“Americans exchange numbers and Facebook and never hear back from each other. It’s puzzling but they do it to show openness,” says Moira Delgado, the Outreach Specialist for Services for International Students and Scholars. “For Americans, when they ask for your number, they are expressing a possibility of a friendship, more than a promise to be in contact.”

Delgado is used to dealing with the different culture clashes that occur when international students arrive in Davis, and she recognizes Noro’s confusion. In America, there is a paradox because an American showing friendliness does not necessarily mean that he/she has the intention to become friends. Meanwhile many internationals assume that the exchange of phone numbers will lead to some kind of follow through.

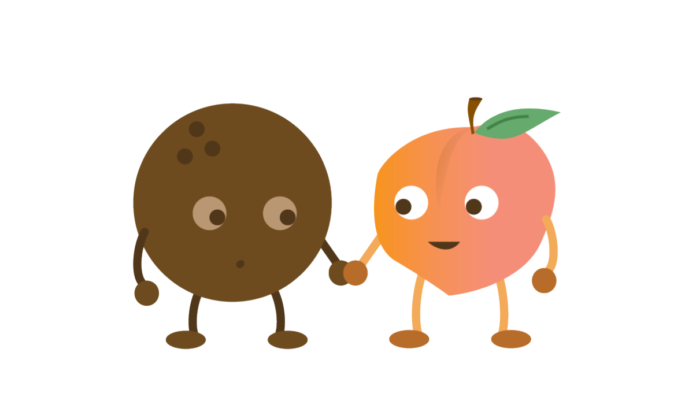

Peaches and coconuts

An analogy that has struck a chord with many exchange students is the comparison of Americans to peaches and many other nationalities to coconuts. A colleague of Delgado once described how Americans are peaches – they are soft on the outside, easy to approach, but the pit is harder – it’s harder to get to know an American really well and to create a real friendship. In contrast, many other nationals will be like coconuts. It is hard to get inside, but once you are there, it is pleasant and you are real friends when you have gotten through the tough exterior.

Jeehye Choi, a 20-year-old chemistry major from South Korea, agrees with the peach analogy. She wants to build close relationships, but she doesn’t feel she can do that with Americans. They are peaches to her. It is too hard to get close to them. She also thinks that the analogy describes Koreans:

“It fits a 100 percent. Koreans are definitely coconuts. If a Korean stranger smiled at you in the streets of Seoul, you’d think he was really weird.”

Choi prefers that people are genuine, and that they only smile if they mean it. In America, people smile at strangers, but it is often not genuine:

“Americans are nice, they smile, and they try to help. They pretend to be friendly,“ Choi says. “They have an obsession with being nice to everyone, but I can see if it is a fake smile. I’m not stupid. When Americans ask me how I am and I answer, they have a certain smile. It’s big, but it’s bored if my answer is too long or if the answer is not great.”

The origin of friendliness

Many foreigners are surprised to discover how friendly Americans are when they arrive in America. Strangers talk to each other, the cashier at the supermarket asks how your day has been, and you strike up conversations with people who are standing in line with you. For Europeans, who tend to keep a certain distance from strangers, this at first is a welcome change, but when they realize that “how are you?” only means “hi,” they often see it as a lack of genuineness from Americans.

Delgado points out that there is a historical reason why Americans are friendly towards strangers. Americans are a mobile people. Historically, they have had to move around a lot, and they have needed to make connections quickly, but also to be able to let go of those connections. It also has to do with their deep sense of being independent and not relying on other people because once you have a deeper relationship, you also become dependent on that person.

The ability to let go easily is not something that goes unnoticed by international students.

“People are very nice and I like them but I know the relationships won’t go any further. Americans don’t care after you split up,” says Tina Rodriguez, a 23-year-old law student from Switzerland. “Americans appreciate the moment, and when they are there, they are there. They listen to you, but the next day they have forgotten your name.”

The definition of friendship

An important factor is also how Americans and internationals define friendship. Americans call other people their friend very easily. It is a term used loosely – perhaps because the English language does not offer any viable alternatives. According to Delgado, “acquaintance” sounds too cold and too remote. Especially among college students.

Evelyn Alper, a 21-year-old American national and food science major, somewhat agrees. Her definition of a friend is someone who loves you for who you are, who would help you in any situation, and someone you have fun with, but she realizes that she probably uses the term differently because most Americans use it for both intimate friends and for acquaintances.

“Americans use the word ‘friend’ for someone they would say hi to and have a casual conversation with,” Alper says. “Generally, Americans would call somebody a friend even if they know the person is not somebody who would be there in situations where a real friend is needed.”

At first, many international students feel happy that they so quickly become “friends” with Americans, but the enthusiasm fades when they get to observe Americans for a longer period of time and see how easily Americans deem somebody their friend. Quickly, the feeling of inclusiveness loses value.

“Sometimes I’m confused,” Choi says. “Americans are always being nice so I don’t know if we’re close or if there’s still a distance between us. I prefer that people say honest things. If there’s something they don’t like about me, I wish they would just say so. Americans are obsessed with being nice.”

What to do?

How do Americans and internationals tackle culture clashes in the best way? One thing Delgado points out is that a good idea is for both sides to consider how they phrase their questions when they ask questions about other cultures. Asking “how” questions and not “why” questions allow conversations about any culture – like asking “How do you show friendship in your country?” while “why” questions limit the conversations and often sound accusatory even if they were not meant to – like Why do you say I’m your friend when you don’t mean it?”

Delgado points out that you also have to think in the framework of a particular culture. It might be true that asking a stranger “how are you?” in a supermarket in France would be superficial because nobody cares about the answer, but in America it would be considered rude if you didn’t say hi. Instead of feeling affronted, people should realize that the characteristic they are looking for, for example friendliness, might be missing in a person in a particular situation, but that it is often possible to find that characteristic in the same person but in another situation.

“If Americans analyze the French from their American cultural reference, it is true that the French appear cold and snobby, that they don’t engage in conversation in public,” Delgado says. “If you go back to America, it is true that somebody with that behavior is rude, but in France it is not necessarily so. Beware of what framework you are judging from.”

According to Delgado both Americans and foreigners can learn from each other. Foreigners have to realize that they have to take the initiative. If an American says “we should go to a movie sometime,” the foreigner should follow up and be specific. The foreigner should ask which movie and which day. Otherwise, it likely will not happen.

At the same time, Americans should learn not to be afraid of taking part in deeper conversations which they often refrain from because they don’t want to cause conflict. In some cultures, it is okay to discuss politics but Americans tend to be more guarded.

“Internationals complain that Americans only want to talk about sports and the weather, and it’s not because they’re superficial, Americans just don’t want to upset the balance,” Delgado says. “It’s okay for some people to talk about politics.”

For Noro, who was rather disappointed by the outcome of what he saw as a profound conversation, his perception of Americans is somewhat pessimistic:

“I think Americans feel sociable by talking and asking for a phone number. They are satisfied with that. They connect over banalities that don’t lead anywhere, and it becomes boring.”

Not all internationals are deterred by Americans and their easy-going friendliness. Tina Rodriguez is in America for the third time and has realized that Americans rarely keep in contact, but she has accepted that and now quite likes their behavior:

“I think I prefer the American way even though it is fake. I like to see everybody smiling and happy even though I know it is not possible that everybody is.”

KRISTINE NØDGAARD-NIELSEN is a contributing writer for The Centennial Magazine.

Graphic by Jennifer Wu.