Experiments focus on inhibitor of soluble epoxide TPPU, which reduces inflammation and neuropathic pain linked to depression

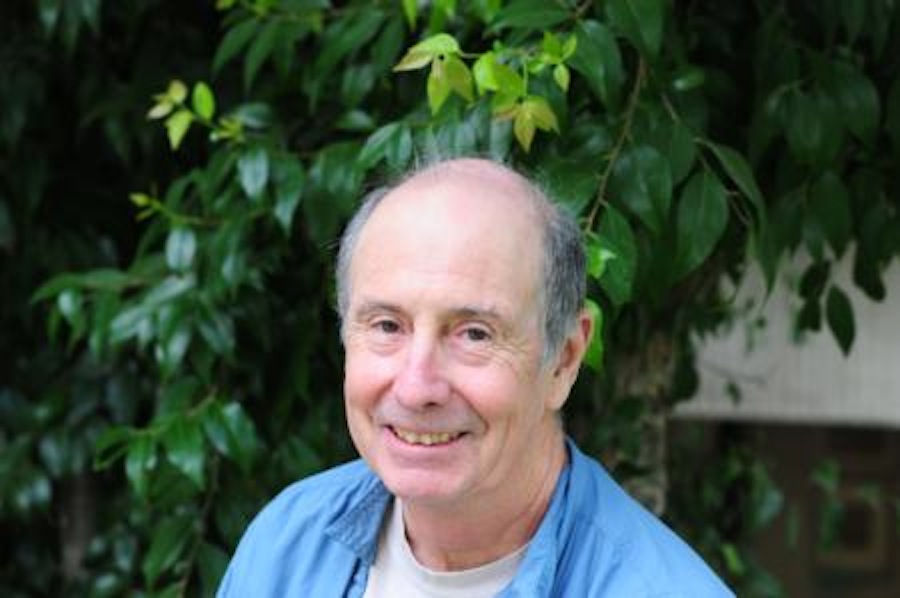

Bruce Hammock, a professor within the entomology department at the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center, recently discovered in his laboratory a chemical that can help control the chronic disease of depression.

The research was published on March 14 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and it involves the studies of an inhibitor of soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) in rodents. SEH is the chemical working as a therapeutic target acting on a number of inflammatory or inflammation-linked diseases.

“The research in animal models of depression suggests that sEH plays a key role in modulating inflammation, which is involved in depression,” Hammock said in an article for The Davis Enterprise. “Inhibitors of sEH protect natural lipids in the brain that reduce inflammation and neuropathic pain. Thus, these inhibitors could be potential therapeutic drugs for depression.”

Researchers from Hammock’s laboratory collaborated with depression expert Kenji Hashimoto and colleagues at the Chiba University Center for Forensic Mental Health in Japan, and together examined the role of the potent TPPU in a rodent model of depression classified under “social defeat.” The social defeat model caused the rodents social stress.

The researchers found that TPPU displayed rapid effects in both inflammation and social-defeat-stress models of depression and that expression of sEH protein was higher in key brain regions of chronically stressed mice than in control mice.

In the experiment, pre-treatment with TPPU prevented the onset of depression-like behaviors in mice after induced inflammation or repeated social-defeat stress. Mice lacking the sEH gene did not show depression-like behavior after repeated social-defeat-stress.

These are significant findings because researchers have discovered that postmortem brain samples of patients with psychiatric diseases such as bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia have shown a higher expression of sEH than in control groups.

Karen Wagner, a researcher at Dr. Hammock’s lab, believes these findings are important because of the chemical’s rapid effects on the experimental mice.

“These results were pretty quick,” Wagner said. “Current antidepressants take weeks to have full effects, but the sEH inhibitor was pretty rapid.”

Christopher Morisseau, another researcher who worked with Hammock in his lab, believes this new approach can be successful.

“It was a 1+1 solution,” Morisseau said. “Right now, when people take depression drugs, they expect neurons to talk to each other. Here we try a different approach. Because the current approach doesn’t work, we believe changing it can help.”

Researchers in Hammock’s lab plan to continue researching this discovery by performing more experiments and focusing on models of depression.

Written by: Demi Caceres – campus@theaggie.org