UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain launches The Cochlear Implant project, seeks advancement in auditory, linguistic communications

Two out of 1,000 children born in the United States every year have detectable hearing loss in one or both ears, according to the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). Researchers at the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain are collecting data for The Cochlear Implant Project to observe the development of the brain after children receive medical devices for auditory improvement.

The cochlear implant (CI), an electronic device that helps deaf or severely hearing-impaired persons to hear, uses electrical signals to directly trigger the auditory nerve. The inner-ear functions that relay sound pressures into electrical signals are often dysfunctional in deaf patients due to a wide variety of reasons, such as fusion of inner-ear bones or trauma.

CIs deviate the inner ear pathway, making them extremely helpful for patients who are hearing-impaired.

“Most children are implanted [with a CI] by 1 or 2 years of age,” said David Corina, professor of linguistics and psychology and researcher at the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain.

The Cochlear Implant Project at UC Davis researches the impact these medical devices have on the hearing and language development of deaf children.

“More and more children are getting CIs and the technology is getting better,” Corina said. “What is the role of sign language now with children with a CI? Is it beneficial or distracting?”

Parents of the study’s participants also ask this pressing question. Families are very engaged in this project and often look to the researchers to help them find the best strategies of communication treatment and development for their children.

“[Finding the best strategy for each participant] can be challenging, as many parents are quite busy and some travel significant distances to get quality services for their children,” said Laurie Lawyer, postdoctoral scholar in the Cognitive Neurolinguistics Laboratory at the Center for Mind and Brain.

The researchers work with families to obtain background knowledge of their children, including previous medical conditions, as well as their home and school situations.The researchers also orchestrate programs that support the transition of deaf and hearing-impaired children into mainstream schools. These programs help students succeed in communication and functional learning.

The young participants involved in this CI study come from multilingual backgrounds both at home and at school, with sign language as one of their fluencies.

Variations of sign languages exist depending on factors like geographic location.

“Britain has its own sign language, and so do other areas like Turkey and Hong Kong,” Corina said.

The CI project looks at linguistic competence by comparing the different types of languages; this includes both verbal and sign languages.

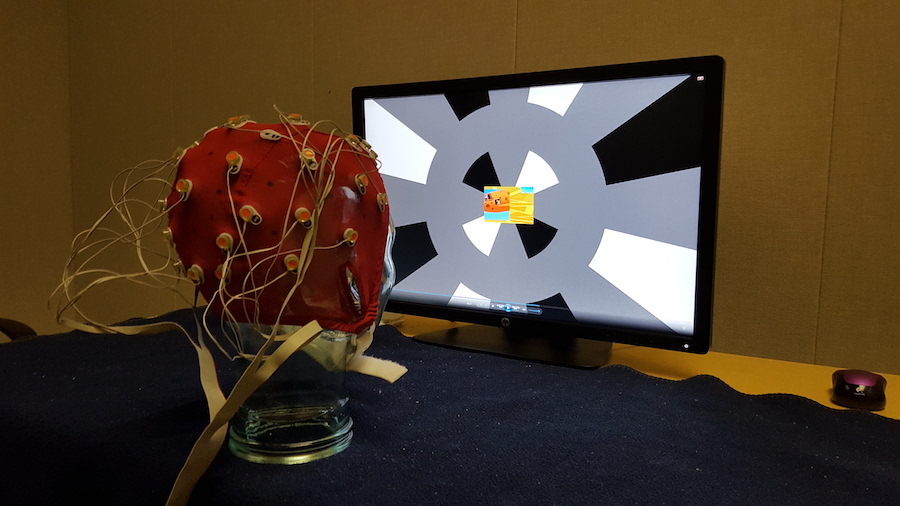

The technology used in this project includes electroencephalograms (EEG) to look at the electrical activity of the brain. Diagnostic exams involve eye-tracking tests, as well as standardized language and intelligence tests.

“In our lab we give children and parents a tour of the testing facilities and equipment prior to their participation,” Lawyer said.

The children grow accustomed to the environment at the research center.

“[We let parents] try on the EEG cap, see the electrodes and touch the electrode gel long before we attempt to put them on the children,” Lawyer said.

If at any time the child feels uncomfortable wearing the EEG cap, they are not forced to participate.

“The electrodes [on the EEG cap] record electrical activity created by the simultaneous firing of a group of neighboring cortical neurons,” said Andrew Kessler, a junior specialist researching CIs at the Center for Mind and Brain.

The researchers seek to have a better understanding of brain development after cochlear implantation.

“Our carefully-designed experiment provides a rapid and noninvasive neural metric of this population’s visual, auditory and linguistic processing,” Kessler said.

Participants from 1 to 2 years of age to about 8 years of age are recruited. It is important that data collected occurs from CI patients that are still developing their brain after the implantation of a CI.

“The goal of our current research is to characterize the relationship between visual and auditory processing in deaf children with cochlear implants, to track whether this relationship changes over time and to relate each child’s auditory and visual processing abilities to language and other behavioral outcomes,” Lawyer said.

The CI project is a five-year longitudinal study that encourages the families and participants to return for more data collection.

“In 5 years we should have collected enough data to make some conclusions about how the brain changes as a result of receiving a cochlear implant, and how that relates to clinical outcomes for these patients,” Kessler said.

The CI project is a unique study that gives participants and their families hope via better learning and developmental communication strategies necessary for the children to succeed.

“We’d eventually like to be able to develop a set of diagnostic tests which could be used prior to implantation to determine which kids may show the greatest benefits from a cochlear implant, and which kids may be better served by alternative means,” Lawyer said.

This project is paving the way for more effective and efficient treatments for children with auditory impairments.

“Getting to interact with the families reminds me of why we do this kind of work, because ultimately, we’re all trying to give these children the best possible chances for success,” Lawyer said.

Written by: Shivani Kamal – science@theaggie.org