Barry Jenkins’ film is subtle, gorgeous — and urgent

It can seem flippant, even callous, to write a movie review at a time like this. In the wake of shock and horror, as the nation and the world reel from the realization that it can happen here, as we come to terms with dark and difficult times ahead — aren’t there more important things to talk about than movies, than art?

At the moment, I can’t think of anything more important to talk about than art. Especially when the art in question is as extraordinary as Moonlight, director Barry Jenkins’ critically-acclaimed film about a young black man struggling to understand his sexuality in a rough neighborhood of Miami at the height of the War on Drugs.

Moonlight is told in three acts, titled “Little,” “Chiron” and “Black,” vignettes of Chiron’s childhood, adolescence and adulthood. As a child, played by Alex Hibbert, he is full of wide-eyed innocence yet cagey and taciturn, a too-old-for-his-years product of rough streets and a rough home. He is discovered hiding from schoolyard bullies in a crack house by Juan, played by the incredible Mahershala Ali, who takes him home; Juan’s neat, quiet house becomes a refuge for Chiron — clean sheets, warm meals, a father figure, none of which he has at home.

But this life is a fantasy, a facade, and Chiron has questions that Juan can’t answer. “My mama does drugs?” he asks Juan, over dinner, putting the pieces together. “And you sell drugs?”

Another question, over another dinner: “What’s a faggot?” Juan stumbles for an answer, and Chiron presses him: “Am I a faggot?” It’s the way he asks these questions, his voice flat and his gaze unblinking, that tears your heart out.

Finding the sweet spot between specificity and universality is one of the eternal problems of art: too specific, and you alienate the majority of the audience; too general, and good stories turn into fabular cliches. Moonlight is one of those rare films that walks the line between the two, and although it touches on universal issues, it would be only half-true to call it a coming-of-age film about love, identity and family. This is a film about a queer, Black life.

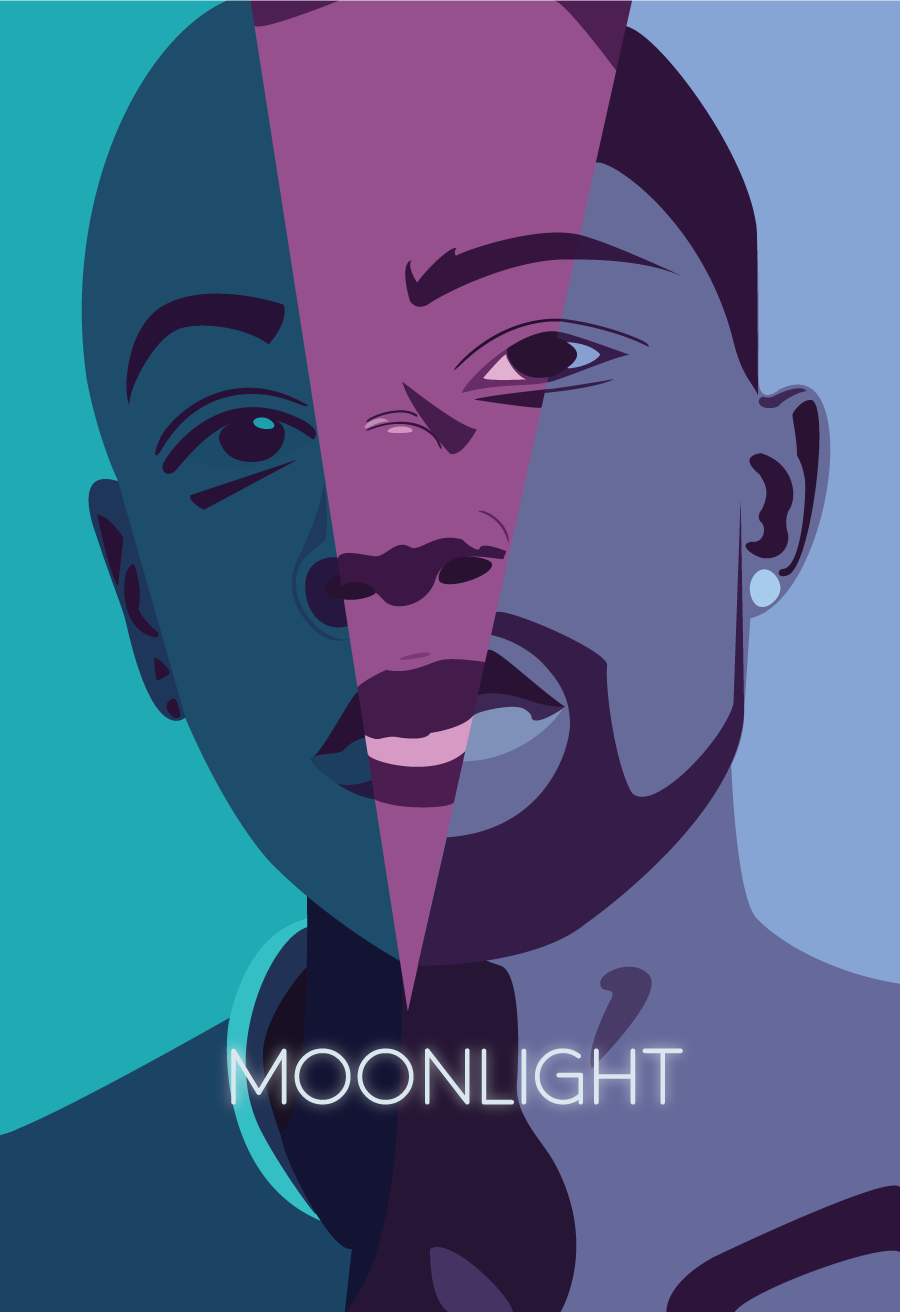

Moonlight may be one of the best films of the year, but it’s also one of the most beautiful. Film and TV are getting darker — “peak TV” has brought us a bevy of prestige dramas so low-lit and shadowy that they’re almost impossible to watch — but Moonlight is shot in Miami’s sun-bleached pastels and rich neons. The scenes at night are especially striking; rather than the usual black and gray, Chiron’s nights play out in shades of lush indigo, violet and gold. The soundtrack is an eclectic mix of 60’s Motown and soul, 90’s hip-hop and composer Nick Britell’s spare, haunting orchestral score, which fit together with surprising ease.

Coming-of-age films often fall into the same stock narrative, but Jenkins sidesteps the tropes of the genre: in the third act, Chiron is grown, but he’s back at the beginning of the circle, selling drugs in a do-rag like Juan, still adrift and unsure of himself. An out-of-the blue phone call from Kevin yanks him back to Miami — Kevin, a high school friend who kissed and loved Chiron before falling prey to the hunt-or-be-hunted law of high school and beating him bloody after class, and who Chiron says is still the only man who’s ever touched him. Affection between men is rare in film, and between men of color it’s even rarer, but Kevin holding Chiron’s head, stroking his hair, is gentle and tender, a fleeting moment of genuine love in a lonely world.

Barry Jenkins has created a masterpiece — Moonlight is subtle, sublime and as close to perfect filmmaking as you can get — and it couldn’t have come at a more perfect time. In a country bitterly divided against itself, Moonlight accomplishes what all the campaign outreach teams and calls for unity and understanding couldn’t. It’s why we read books and watch movies at all: to feel and know a life and an experience other than our own. Right now, that might be the most important thing in the world.

Written by: Emily Stack — copy@theaggie.org