Kim Keever incorporates engineering education into otherworldly photographs

Kim Keever incorporates engineering education into otherworldly photographs

Well, Aggies, the dreaded finals week has finally arrived. I only remind you in case you forgot, even for the slightest second, about your soaring levels of stress, plummeting amount of sleep and flatlining social life. You’re welcome.

Finals week also signals my end as your guide through the magical land of the humanities and sciences. Tragic, right? It’s been a blast analyzing just a small fraction of the ways in which the arts and sciences intersect, and I’ll certainly miss all five of my readers. That said, I can think of no better send-off than delving into the photography of one of my favorite artists, Kim Keever.

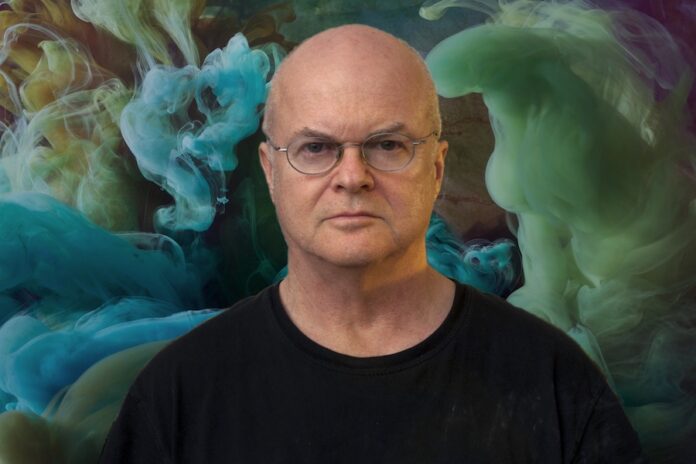

Before the New York City-based artist turned his professional attention towards photography, Keever studied engineering at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va. and interned for NASA in the summers.

“I actually went through almost six years of engineering school — which is a tremendously tough schedule — without any serious interest in being an engineer,” Keever said via e-mail. “I know that sounds crazy, but my grand plan was to make a lot of money as an engineer and eventually retire and become an artist full-time after that. I reached a point in my life where I realized I only had one life that I knew of, and it made perfect sense to just give up on engineering — by now I was already finishing graduate school — and follow my true love, which was making art.”

Although Keever decided against a career in engineering, his scientific background shines through his art, resulting in pieces that seem possible only from an individual with one half of his brain in the artistic world and the other half in the scientific.

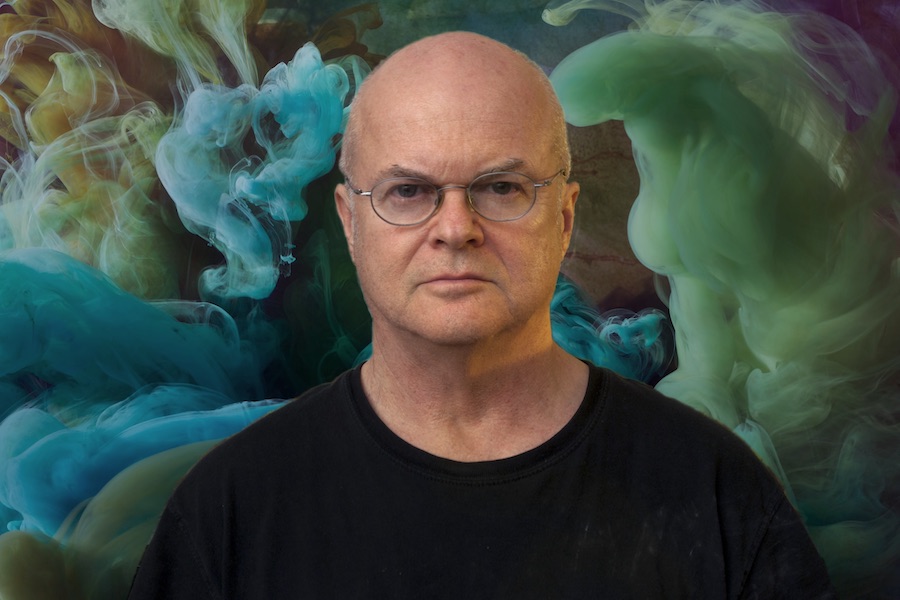

Keever’s work feels timeless, bottomless, infinite — yet the whole process takes place in a 200-gallon fish tank. The engineer-turned-artist assembles his own microcosms, often ethereal depictions of nature, that he then submerges in the water-filled tank.

“My engineering background has always allowed me to build sets that last long enough for my projects,” Keever said. “For example, I used a Christmas-tree rotator to rotate a lightweight circular platform I made, which held a pillow stuffing sky attached to a circular piece of translucent mylar. It rotated in back of the tank for a video project.”

After submerging a piece, Keever drops paint into the aquarium and photographs the ways in which the colors and light diffuse and mingle with one another. Even though he controls the lighting, sets and paint colors, Keever ultimately relies on the laws of fluid dynamics — the behavior of liquids and gases in motion — to create his otherworldly artwork.

“The fluid flow dynamics class was really one of my favorite classes in graduate school,” Keever recalls. “It was very visual and was made up of drawings of how a fluid would react when it flowed into a wall or a corner or other type of configuration. I certainly never realized it would come in handy with my art until recently.”

The mixture of descending paint drops and realistic landscapes allows Keever’s lifelike photographs to emulate scenes in nature. Some capture the beauty of splintered light pouring through clouds, mountains and trees; others mimic the moodiness of water spraying over powerful, stormy seas.

But Keever’s art isn’t just beautiful (although that’s certainly the first adjective that comes to my mind). His photographs consistently arouse complex and often paradoxical emotions in viewers. West 104k (2009) presents a mountainscape that immediately recalls tranquility, gratitude for nature and — luckily for Pinterest users — wanderlust. But the photo is equally unnerving, summoning an intimidating sense of seclusion in its endless stretches of uninhabited land.

Wildflowers 52i (2008), another personal favorite, depicts colorful mist dawning over a lush flower garden. The vibrant, mystical scene is both comforting and eerie, bright and haunting, joyful and apocalyptic. It’s the type of art whose magic is difficult to put into words but can be intuited by the audience.

Keever ultimately creates worlds that are distinctly recognizable yet different from anything else on the planet. His art pieces gnaw at one’s mind and call forth a string of disquieting questions. What lies beyond the misty haze? Do these scenes reflect a time before, during or after humankind? Do the landscapes even belong to Earth?

Keever has recently turned his attention away from landscapes towards more abstract art pieces. Although they lack the homemade dioramas, the photographs still invoke familiar natural phenomena like smoke ascending to the heavens in Abstract 5541 (2013), pastel mud-clouds being kicked up from the ocean floor in Abstract 1931b (2013) and waves tumbling onto a shore in Abstract 15443b (2015).

In The Balloon Series, his latest project, Keever employs balloons of various sizes and colors to add a bubbling texture and sense of limitlessness to his work.

“I found it very interesting the way the paint billows over the top of the balloon and hugs the side of the balloon until it reaches the midpoint,” Keever noted. “After that, it falls in a very interesting way — somewhat like a waterfall.”

The pictures call to mind a boundless collection of worlds floating together among draping confetti and whirling smoke.

“On a three-dimensional scale, I think of these spaces as containing endless universes becoming smaller and smaller,” explained the photographer on his website. “The same is true in the opposite direction. Our universe is contained by other universes, and those are contained by more universes ad infinitum.”

Although switching from engineering to art seems like a fatal choice to many college students, Keever maintains an unwavering confidence in his decision to pursue art.

“I can’t say it’s been easy, but I’m happy I went in that direction with my life,” Keever said.

The artist’s contentment with his decision is no wonder. Besides having his own New York exhibition, Kim Keever: Random Events, Keever’s art has been displayed in cities across America, including San Francisco, Chicago and Washington, D.C. In 2015, Keever snapped a shot of seaweed for a New Yorker article about the wonders of edible seaweed and worked alongside director Paul Thomas Anderson to create a music video for indie-folk musician Joanna Newsom’s song “Divers.”

The artist encourages students to similarly honor their natural passions — whether that includes science, art or something inbetween.

“It probably sounds corny, but it’s best to follow your heart,” Keever advised. “I often meet people who are very well educated but don’t seem to have any real love for what they are doing. Every once in awhile you meet someone who really is excited about the work they do.”

Aggies, I ask that y’all take Kim Keever’s words of wisdom as my parting gift. As the quarter draws to a close, I sincerely hope that my column presented a strong argument for students unabashedly studying the subjects that bring them joy, fulfillment and confidence.

And if I failed at accomplishing this — well, first of all, don’t break my gentle heart by telling me. But, if I failed, I still hope that, at the very least, visions of art and science will dance in your heads throughout the holiday break as you all settle your brains for a much needed, much deserved long winter’s nap.

Written by: Taryn DeOilers — tldeoilers@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.