As Davis’ offensive line goes, so too goes the offense

The Aggies went on the road to Weber State and things did not go well. The following week they faced North Dakota at home and things suddenly went very well. What gives? Three words: offensive line play. Against Weber, sophomore quarterback Jake Maier was under frequent duress, and as a result had less time to find receivers down field for big plays. Similarly, the Aggie rushing attack was inhibited, with the Weber defensive backs frequently contacting Aggie runners behind the line of scrimmage, resulting in fewer yards per carry. Against North Dakota, the offensive line was far more successful. The result was a more efficient and explosive offense with a higher proportion of its plays resulting in greater average gains in yardage.

Digging In

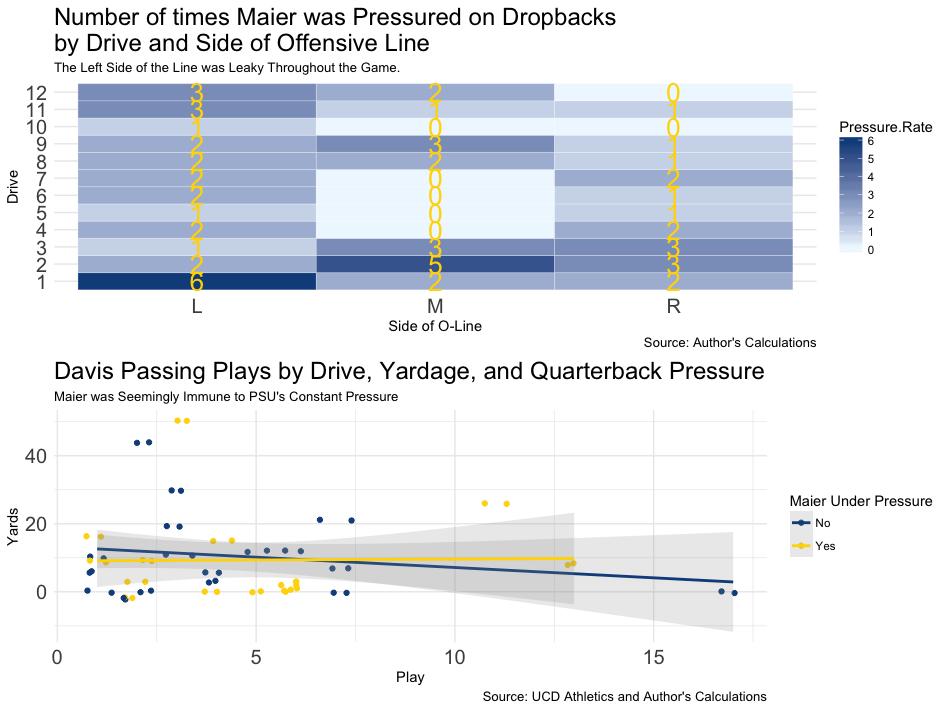

You may remember that during the Portland State game, the left side of the Aggies’ offensive line was somewhat porous. In that game, sophomore quarterback Jake Maier was under near constant duress from the left, but managed to scramble, buy time, and not allow the pressure to affect him. As a quick reminder, here’s two plots illustrating the point.

This was all fine during the Portland State game, because the blitzes weren’t getting home, and Portland State struggled to generate points by any means. Less so versus Weber State, which brought the pass rush early and often.

Two Steps Away from the County Line

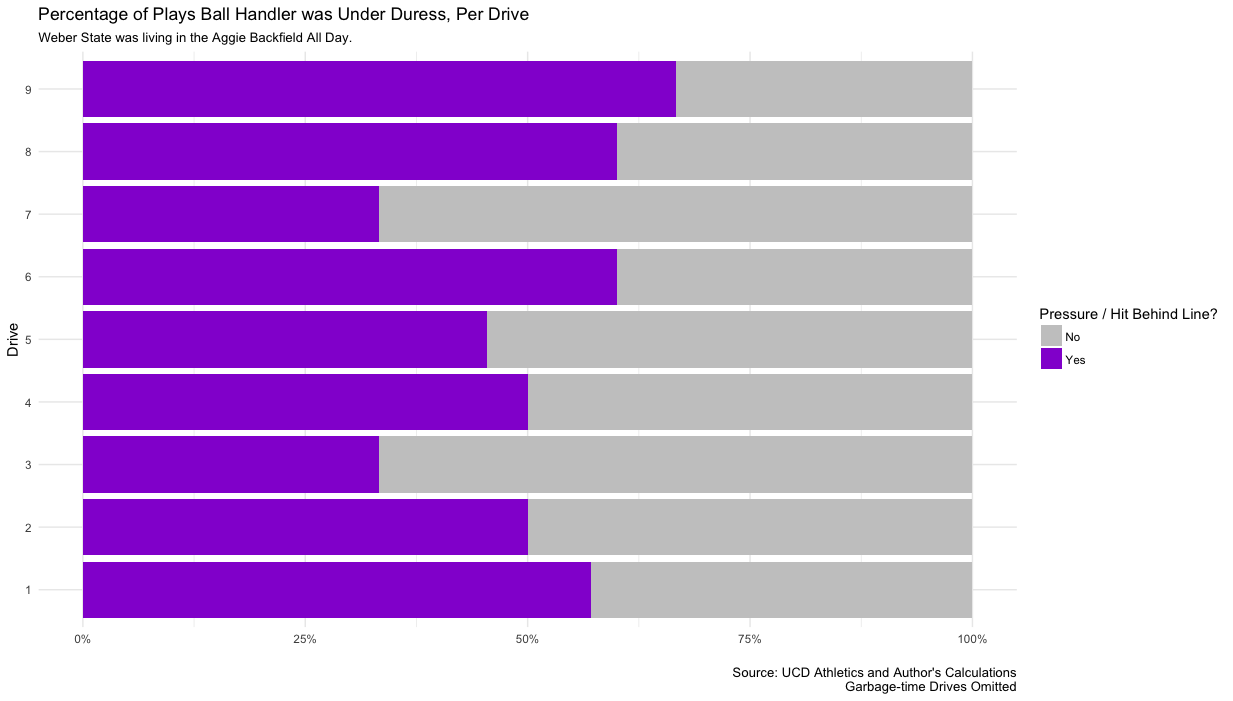

Here’s a bald statement that doesn’t get said enough: offensive line play matters. Columnists don’t typically discuss line play because audiences don’t typically pay attention to it. Why? Likely because most audiences are watching the ball, and guess who rarely touches the ball? You got it, the big fellas up front. Instead, we talk about running backs who accumulate absurd yardage totals, or a quarterback’s stunning efficiency . It’s much harder to appreciate the right guard’s ability to pull to the left side, seal the B-gap, and generate a nice running lane for his H-Back. Nevertheless, offensive line play matters, and it mattered against Weber. Here’s two plots that encapsulate why the Aggies got blown out in Utah.

Yikes. That’s not what you want to see. During the Aggies’ nine, non-garbage time offensive drives, the quarterback was pressured or the running back was hit behind the offensive line 48.1 percent of the time. Okay, no matter, maybe lightning struck twice and it was like the Portland State game, where Maier navigated the pocket so well the pressure didn’t affect him?

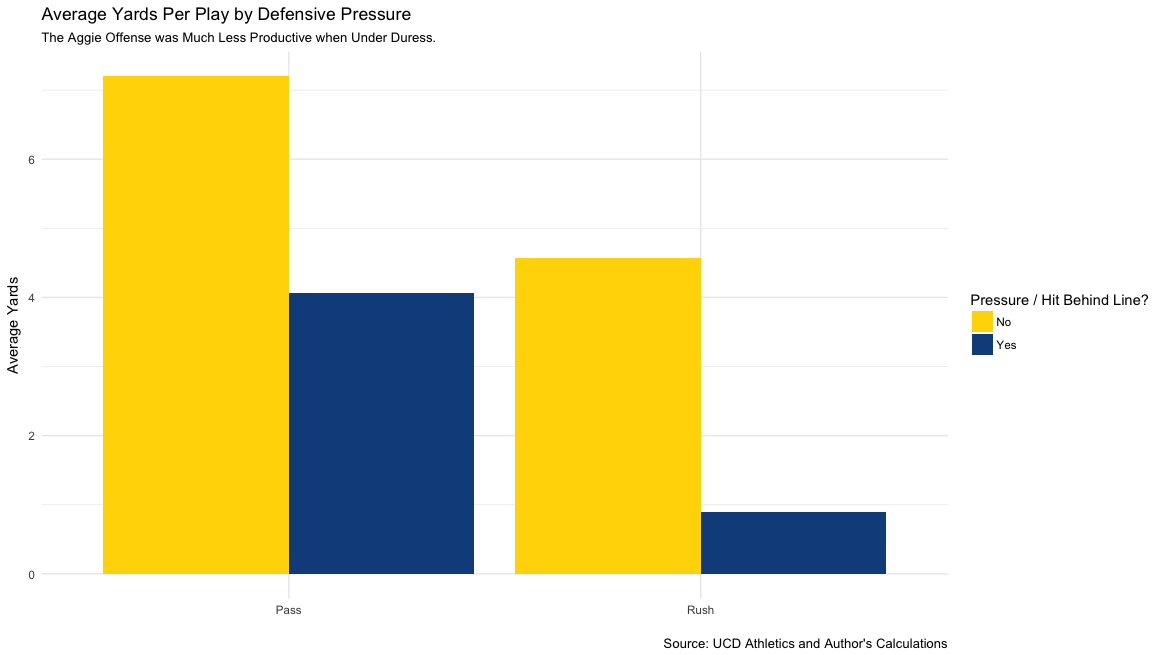

No, that didn’t work out quite so well in this contest. As one would expect, Maier threw for fewer yards on plays in which he was forced to elude the Weber front seven, and the two primary ball carriers in this game — running backs Namane Modise and Tehran Thomas — were far less successful on plays they were hit before making it back to the line of scrimmage. Contrast these outcomes with the rebounding win over North Dakota where the protection was much better and everyone on the Aggie offense got to live their best life.

Deja vu! Maier to Doss for a 65-yard completion and another AGGIE TOUCHDOWN. @UCDfootball leads 14-7 with 12:03 left in the 1st. #GoAgs pic.twitter.com/rzRZilOxTy

— UC Davis Football (@UCDfootball) October 1, 2017

Watch Maier’s eyes and footwork on this play. Shortly after taking the snap, he drops back and glances right as he sees a North Dakota defender bearing down on him, likely triggering flashbacks in Maier of what had befallen him the week before. However, upon seeing the running back and right tackle upend the defender with a combo-block, Maier calmly plants his feet, strides forward in the pocket and delivers a tight spiral to all-conference superhero junior wide receiver Keelan Doss.

Similarly, let’s see what life was like for the rushing attack in this game.

TOUCHDOWN AGGIES! C.J. Spencer takes it to the house with a 5 yard run. We’re 1:59 min in and the Aggies are on the board 7-0! #GoAgs pic.twitter.com/2eRUwY03wB

— UC Davis Football (@UCDfootball) October 1, 2017

That’s some good, clean living for junior running back CJ Spencer, who isn’t touched by a defender until he’s inches from the goal line. Senior right guard Julian Bertero does a fine job pulling from the right side of the formation to the left and blocking the safety who steps up to try and make the emergency tackle at the goal line, to no avail. The result is Spencer cruising to the goal line, letting his momentum carry him the rest of the way. Life is good when you can hold the line.

Just how much better is it?

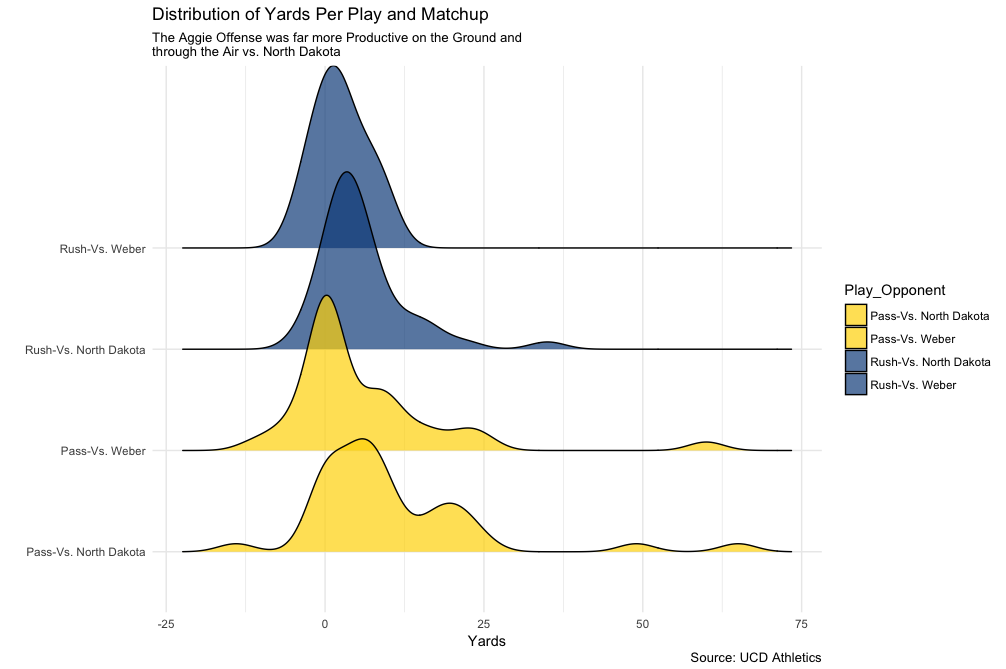

Yeah, it’s a lot better. Notice those distributions from the Weber game are both clustered at or around zero. That’s because the Aggies averaged 2.5 yards per rush against Weber, and 5.8 yards per pass. In contrast, against North Dakota, the offense averaged 5.9 yards per carry and a whopping 10.3 yards per pass. Those differences should speak for themselves, but to reinforce the point, recall an efficient first down play is one that generates 50 percent or more of the needed yardage, meaning an average of 2.5 yards per rush is grossly inefficient, while 5.9 yards per rush will keep your offense humming and on schedule.

Red Light, Green Light

College football stats heads will likely know that there are five factors closely correlated with winning football games. The fifth of these factors is the notion of finishing drives, or what some call “Green Zone Offense.”

Most regular consumers of football are familiar with the “Red Zone”—i.e. when the offense is within 20 yards of the opponent’s goal line. Expanding the “Red Zone” gives us the “Green Zone,” or any time the offense is within 40 yards of the opponent’s goal. This may seem generous, but think about it: if you cross the 40, you’ve either put together a drive that’s worked for at least a few plays, or you’ve inherited excellent starting field position. This means if you have a drive that’s worked so far, it would be a shame to waste it and come away with no points. Couple that with the importance of explosive plays (it’s hard to string together a bunch of little plays), and the impressive range of some kickers, and you can see why the ability to finish drives is a strong predictor of who wins the ball game.

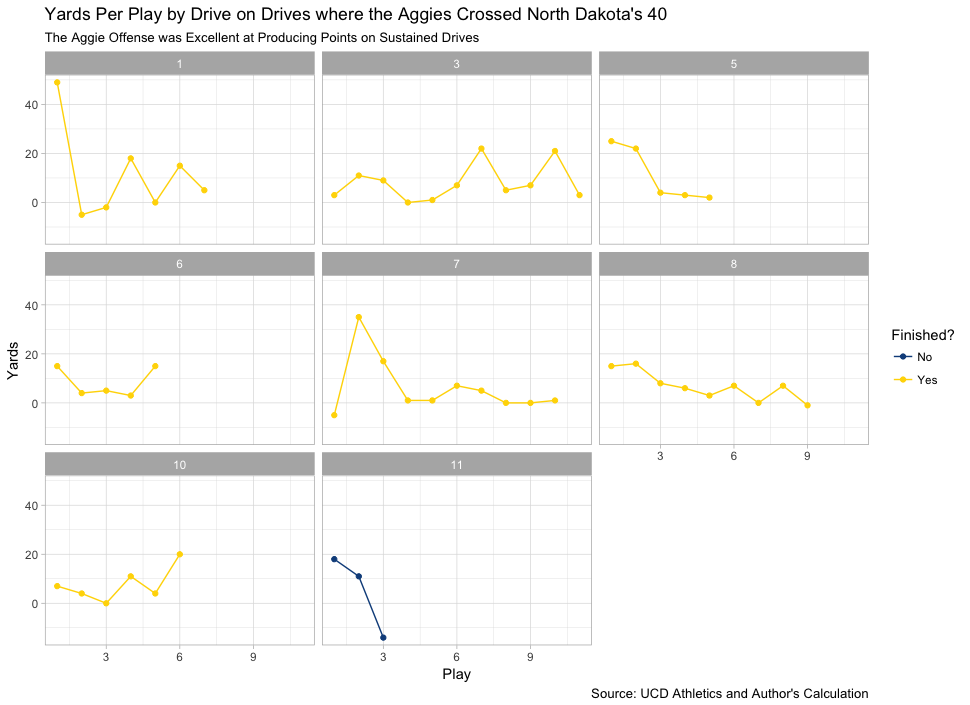

How did the Aggies do at finishing drives against Weber? Well, they only scored three points, so I’ll spare you having to look on that visualization. Let’s jump to the game against North Dakota instead.

That looks pretty good! On all but one drive where the Aggie offense entered the “Green Zone,” they successfully finished the drive and came away with points. More specifically, the offense generated 5.125 points per drive on drives crossing North Dakota’s 40 yard line. Per Football Study Hall over at SB Nation, a team averaging between five and five and a half points per drive on such drives, goes onto win the game 68.4 percent of the time. Couple this with the knowledge that the Aggie offense was also quite explosive, see:

That’s one way to start the game. Maier connects with Doss for a 49 yard pass on the first play of the game! #GoAgs pic.twitter.com/Ec4SuBnSdB

— UC Davis Football (@UCDfootball) October 1, 2017

and life starts to look pretty good.

Dispelling Myths

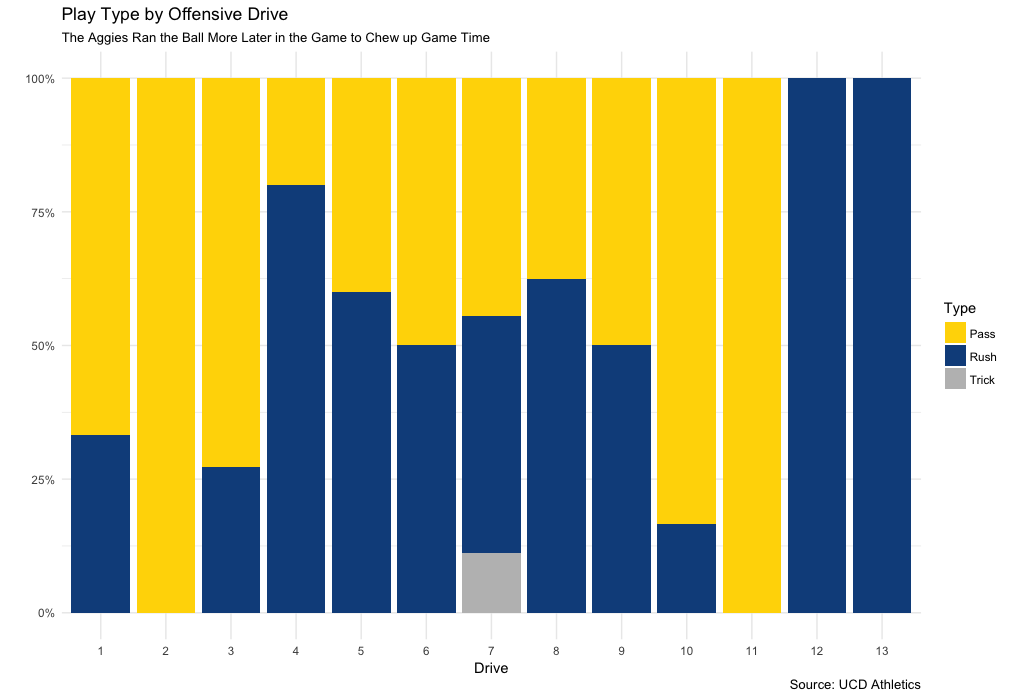

On a final ancillary note, I wanted to take the old adage that teams who run the ball more, win. The intuition behind this follows the thinking that a tough, gritty football team, willing to run the ball more, will inevitably tire out its opponent, and go on to win the game. In fact, it has long been shown this statement inverts cause and effect. In truth, teams who are winning run the ball more.

Here we see the distribution of passing and rushing plays by offensive drive. Note that earlier drives are composed of a little more than 50 percent passing plays. However, at the end of the game, the Aggies’ final two drives are 100 percent rushing plays. Why? Because running the ball does two things: it limits turnovers from interceptions, and it keeps the game clock moving by reducing the number of clock stoppages from incomplete passes.

Wrapping Up

Thanks for spending some time parsing the numbers and tape with me. Football is a challenging game to discuss rigorously because of the number of moving parts and sheer number of players associated with each play. The problem is compounded by the dearth of deeper statistics to work with. For example, in scrutinizing quarterback play, average air yards per attempt (how many yards the ball traveled through the air) is often a better indicator of a quarterback’s skill throwing the ball, than more familiar stats like yards per completion. Unfortunately, richer data is often hard to find for FCS programs, as they garner less media attention and generate less revenue.

Regardless, I hope you’ve found this statistical deep dive into the program helpful and enlightening.

Written By: Justin Goss — sports@theaggie.org

Disclaimer: The following content was a guest article written for The California Aggie by a class of 2014 UC Davis alum Justin Goss. For more access to articles written by Goss, visit his content here.