Gene found in zebrafish may advance cancer research

A tiny fish is making a whale of a contribution toward cancer research at UC Davis. In a paper published in PLOS Genetics by Bruce Draper, a UC Davis associate professor, recent research may propel the discovery of a cause of ovarian cancer.

While it may seem strange to use a fish as a model system for a disease found in humans, zebrafish and mammals share many similarities. The fish, no larger than a fingernail, have a liver, brain and eyes, among other organs. Moreover, 84 percent of the genes related to ovarian cancer are present in zebrafish, making it an ideal model organism.

Within months, the species can procreate three generations. Embryos develop outside of the womb, so the mother is not harmed. The reproductive and ethical efficiency of using zebrafish makes for exemplary research methods.

“Reproduction to sexual maturity is only three months, which is much faster than a monkey or other primates,” said Sydney Wyatt, a graduate student researcher. “A pair of zebrafish can produce hundreds of offspring whereas mice can produce about ten at most.”

Certain researchers have also preferred zebrafish for similar reasons. However, the Draper Lab at UC Davis is unprecedently studying the gonads of this minnow.

Draper’s lab focuses on how the gene fgf24 affects production of another gene, etv4, as well as the signaling pathways in between. The gene etv4 is believed to be responsible for ovarian cancer. In the recent paper, the lab showed that a deletion of fgf24 resulted in an absence in etv4.

“Cancer is often times the reverse of what happens during normal development,” Draper said. “We’ve shown that if you take the gene away you can’t proliferate, but if you over activate it then that should potentially drive a proliferation.”

Though the gene fgf24 is not present in humans, proving that fgf24 relates to etv4 may lead to finding a protein in mammals which performs likewise. The next phase of research would move to studying mice in an effort to find a gene similar to fgf24. If found, this could drive finding a cure for ovarian cancer.

“Several fgfs, their receptors, and their downstream targets are linked to many cancers, including ovarian,” said Dena Leerberg, a UC Davis postdoctoral scholar.

“This particular gene [fgf24] is not in mammals, but genes very closely related to it are,” Draper said. “All the other components of the pathway are present.”

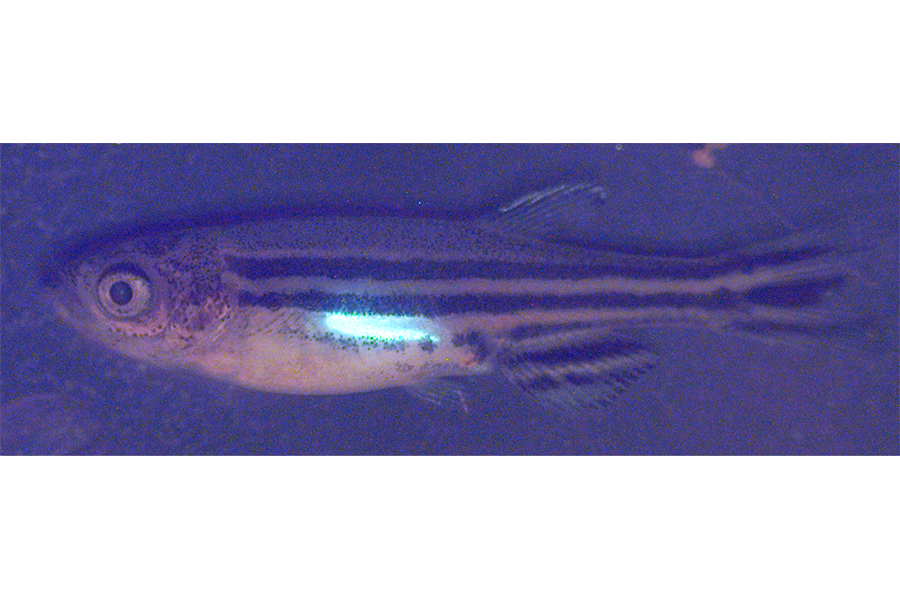

Researchers conquer the zebrafish’s size limitation by genetically engineering the fish to have florescent gonads. Under a microscope, the fish are studied with blue light, making the gonads radiate through the skin. This way, genes contained in the gonads can be studied with less of a headache.

Recent results from the lab may catapult a sea of advancements in cancer research.

Written by: Natalie Cowan — science@theaggie.org