Study shows that gelatin strengthens tendons, ligaments, bones

Kale, acai, quinoa… and now Jell-O? After conducting research on how to strengthen connective tissues like tendons, cartilage, bones and ligaments, Keith Baar, a UC Davis professor in the Department of Physiology and Membrane Biology, found that when it came to impacting tendon strength, gelatin outranked every other food.

Because almost 70 percent of sports injuries are musculoskeletal, it’s important to think about connective tissue. These injuries could impact long-term exercise abilities. With so much attention being given to muscular strength, it’s easy to forget how important the connective tissue can be, especially considering that connective tissue used to be considered static.

If the tendon doesn’t work well, the muscle will fail. But for many years, tendons were thought to be static, undergoing little to no change. However, Baar found that tendons are actually quite dynamic and regenerate quickly.

“They turn over as quickly as our muscle does — a tendon you load a lot like the ACL would turn over in about 60 days,” Baar said. “Same thing with the muscle, it turns over every 60 days. Even the protein in the brain turns over every 60 days. Look at your right arm. In three months, every cell in your right arm will be different. It’s still your right arm, but all of the proteins within it have been turned over.”

To figure out how Jell-O fits into all of this, you have to understand how ligaments work. Baar engineered ligaments to understand how to make them stronger.

“When we first started making [the ligaments], they were really weak,” Baar said. “So we looked to see what we could do to kind of make them better. The protein that makes up the backbone, the collagen, what’s in your tendons, cartilage, bones and ligaments, is a repeating amino acid sequence of glycine, any amino acid and then usually a proline. So every third amino acid is either a glycine or a proline.”

The ligaments Baar engineered already had a lot of glycine but had limited amounts of proline. Proline is an essential amino acid, which means that the only way to obtain it is through diet. And it turns out that the food with the highest amounts of proline is gelatin, by a landslide.

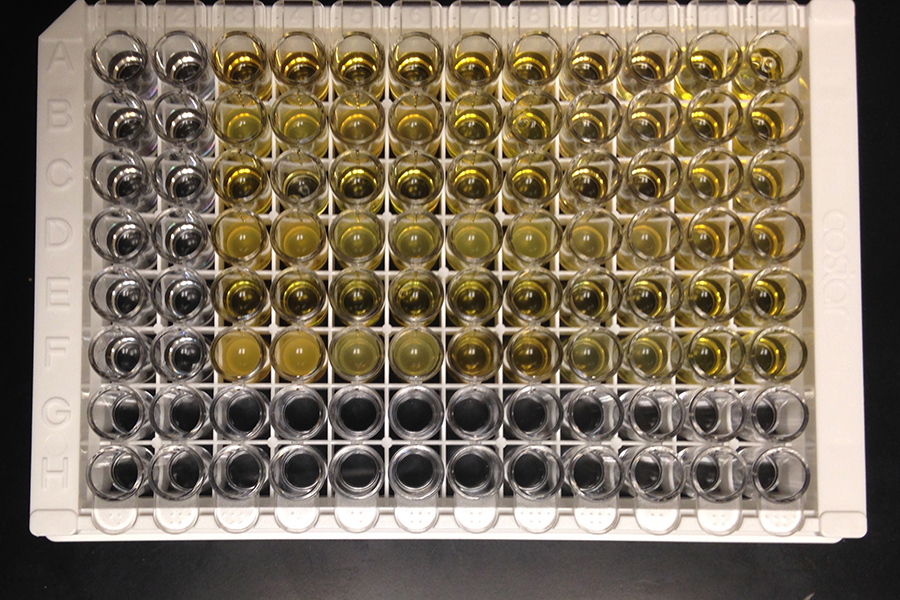

To further study the effects of gelatin in humans, professor Baar worked with the Australian Institute of Sports to conduct a double-blind trial. Greg Shaw, the head nutritionist for Australia’s olympic swimming program, recruited eight people, primarily swimmers, and had them jump rope. For the swimmers, this was essentially an unaccustomed exercise with the landing. Their bones would go through a dramatic response, which would increase the production of collagen.

“What we did is we gave them either a placebo or 5 grams or 15 grams of gelatin,” Baar said. “The goal was to make sure they didn’t know which one they were taking, and all of them did every trial.”

The trial found that when the swimmers jumped rope, collagen production increased. 5 grams of gelatin showed no significant results, but 15 grams led to a further increase in collagen synthesis.

“What that told us is you get an increase in collagen synthesis as a result of the loading,” Baar said. “When you’re jumping up and down, that’s going to provide a stimulus to give you more collagen synthesis.”

Adding 15 grams of gelatin an hour before exercise doubles collagen synthesis. This impacts muscle strength, speed and general health. The quicker and better you turn over collagen, the healthier your body is going to be.

However, not everyone agrees with the idea of gelatin being a superfood. Part of the reason for this could be that there just hasn’t been a lot of research done through randomized control trials.

“Well, I’d like to think that the touted benefits will eventually be supported [by] well designed, human-based RCTs,” said Dana Marie Lis, a postdoctoral researcher in the UC Davis Department of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior and a high-performance sports nutritionist who worked with Baar on this research. “So far, work on engineered ligaments seems promising — but that is only one part of the picture and we still don’t have enough evidence to conclusively determine the best dose and whether all athletes would see benefits in terms of increased collagen synthesis in connective tissue. In sport nutrition we’ve jumped all over this, but I am keen to see if we can replicate and also see if collagen rather than gelatin would have the same effect. Collagen is way more palatable. That is exactly what we are trying to prove.”

La Trobe University professor Jill Cook does not believe that gelatin is really going to make a big difference in tendon strength.

“There is plenty of collagen in tendon pathology,” Cook said. “It is just not structured properly, so adding more is not going to make a difference.”

While Baar believes that increased intake of gelatin paired with exercise could really make a difference, Cook maintains that it doesn’t change the abnormal structure at all.

“Professor Cook doesn’t think that giving cells more amino acid is going to make [the damage] any better and I agree with her,” Baar said. “The difference is what we do together with the gelatin is we give enough of a load to get load in the right direction of those cells.”

Unfortunately, this doesn’t mean that Jell-O has now moved to the top of the healthy food pyramid. Nor does it mean that consuming gelatin is enough. But pairing an increased intake of gelatin with the right kind of isometric exercise may lead to stronger, healthier tendons.

Written by: Kriti Varghese — science@theaggie.org