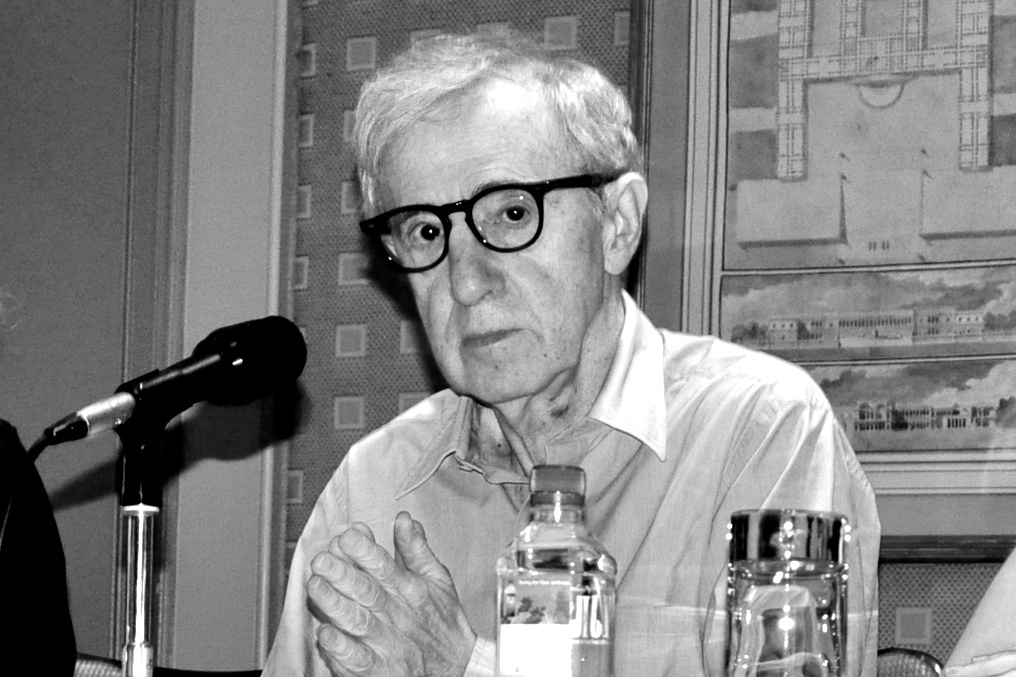

It’s been over 20 years since Woody Allen was accused by Dylan Farrow, his then-seven-year-old adopted daughter, of sexual abuse. Although Allen was never charged and has vehemently rejected the notion that he molested her, Farrow, now 32, has penned several op-eds throughout the past few years reaffirming her initial claims.

It’s been over 20 years since Woody Allen was accused by Dylan Farrow, his then-seven-year-old adopted daughter, of sexual abuse. Although Allen was never charged and has vehemently rejected the notion that he molested her, Farrow, now 32, has penned several op-eds throughout the past few years reaffirming her initial claims.

Allen has made at least one movie almost every year since the allegations came out in 1992 — many of which have either been nominated for or won numerous awards. The Golden Globes, where countless actors denounced the suppression of female voices and mistreatment of women last month, handed him the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012.

It’s becoming increasingly apparent, however, that Allen will not emerge from the #MeToo movement unscathed. Over the past few weeks, individuals in Hollywood have begun distancing themselves from the director; actors have expressed regret over working with him and Goodspeed Musicals, a theater in Connecticut, announced that, “in light of the current dialogue on sexual harassment and misconduct,” it’s cutting ties with his musical “Bullets over Broadway.”

Until now, the “Annie Hall” director had spent his career thriving on the insistence by actors, audiences and critics on “separating the art from the artist” — on letting each work of art stand independent of an artist’s personal life, isolated from the knowledge of his or her actions. To factor in this outside information would be disrespectful, unfair and obstructive to the impact and value of art.

But art springs from the inner thoughts and questions plaguing a creator’s mind. And in the case of Woody Allen, there’s no question that his personal life leaks into his scripts, regardless of Farrow’s allegations. His work displays a decades-long pattern of misogyny and uncomfortable meditations on male-female relationships, according to writer Richard Morgan, who pored over 56 boxes of Allen’s notes from the past 50 years. Characters pursue romantic interests despite striking age discrepancies — always a much-older man with a much-younger woman, often a teenager. And most recently, his overwhelmingly panned “Wonder Wheel” includes a love triangle between a stepmother and daughter, to whom the father “has an unnatural attachment.” This closely mimics Allen’s own very public, very controversial marriage with his ex-girlfriend’s adopted daughter Soon-Yi Previn, who was 19 when the director, 54 at the time, initiated the affair. As film critic A.O. Scott notes, “The principal subject of Woody Allen’s work has always been Woody Allen.”

Yet there’s still an illusion that art belongs to a sacred realm that dare not be touched by our thoughts on the artist’s real life — an air of transcendence that further gets extended to the creators themselves. After all, they’re artists — geniuses, even. They have an understanding of the world that only a select few can access. There’s an otherworldly quality to their artistry that makes up for, obscures or simply annuls their moral responsibilities.

But art is necessarily, irrevocably human. It’s sculpted, penned and played by human hands, formulated by human minds, directed through human lenses. Works of art might reflect something higher, something intrinsically beautiful, but they’re manmade reflections nonetheless. And though art is extraordinarily important to humanity and culture, it should never become so conflated that we allow its creators to slide by without facing their wrongdoings.

We don’t have to cut Woody Allen out of the history of cinema, just as we don’t have to deny the significance of Bill Cosby to comedy or Richard Wagner to opera. But we shouldn’t turn a blind eye to the messy, sometimes heartbreaking connection between art and artists, either.

When a transgressor is actively churning out works, the ethical solution is simple: stop supporting their art to inhibit future abuses. The repercussions should be stern and tangible, as with artists like Louis C.K. and Kevin Spacey. But what’s the right way to interact with art from the past that has been deemed irreplaceable yet controversial?

There’s no underlying rule that says we must constantly deify certain artists because their contributions have been pivotal to their fields. Ceasing to impulsively glorify Allen’s movies does not erase their influence; it merely signifies that our appreciation of art also takes into account the highly flawed mind behind the work. When viewed in this light, Allen’s films can be dissected with a conscious eye for the ways in which they’re unethical. And through this — because none of his films are “sacred” — critics and audiences might find that other filmmakers, those with purer voices and more respectable stories to tell, are more worthy of study and praise.

The era of #MeToo is one of ripping up the floorboards and revealing the sins of those who have frequently shaped our thinking — not to publicly castigate wrongdoers but to rebuild a more equal environment for creative expression. Artists, especially men, have been allowed to operate and maintain their legacies under the defense that they’re artistic geniuses whose art is too important to be marred by their transgressions — a flimsy excuse that no longer suffices.

Written by: Taryn DeOilers — tldeoilers@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.