Focus on pain assessment over pain management linked to opioid crisis

Last month, UC Davis pain experts published a study analyzing pain-related questions on the United States Medical Licensing Examination, revealing significant gaps in how medical students are evaluated in their understandings of pain management.

The USMLE is a three-part test that all medical students must pass in order to practice medicine in the United States. According to its website, it “tests the ability to apply knowledge, concepts, and principles, and to demonstrate fundamental patient-centered skills.”

“This is the most important test of people’s careers,” said Dr. Scott Fishman, the chief of pain medicine at the UC Davis School of Medicine and the leader of the 2018 study, titled “Scope and Nature of Pain- and Analgesia-Related Content of the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE).”

“I’ve been in this field for 25 years and we’ve been looking to improve education around pain for some time but have been failing,” Fishman said. “The public would probably be surprised that pain isn’t taught well. Pain gets forgotten like an orphan. No one ever really established what we want with pain education, the outcomes regarding pain knowledge that we want for someone coming out of medical school.”

Since no official learning outcomes regarding pain management exist, Fishman also worked to publish a set of novel core competencies for pain management that were developed with other medical professionals at an interprofessional consensus summit in 2013.

“A while back, Dr. Fishman and I started looking at the idea of having competencies in pain,” said Heather Young, another senior author of the recent study, an associate vice chancellor for nursing and the dean of the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at UC Davis. “What do people need to know about pain to do a good job?”

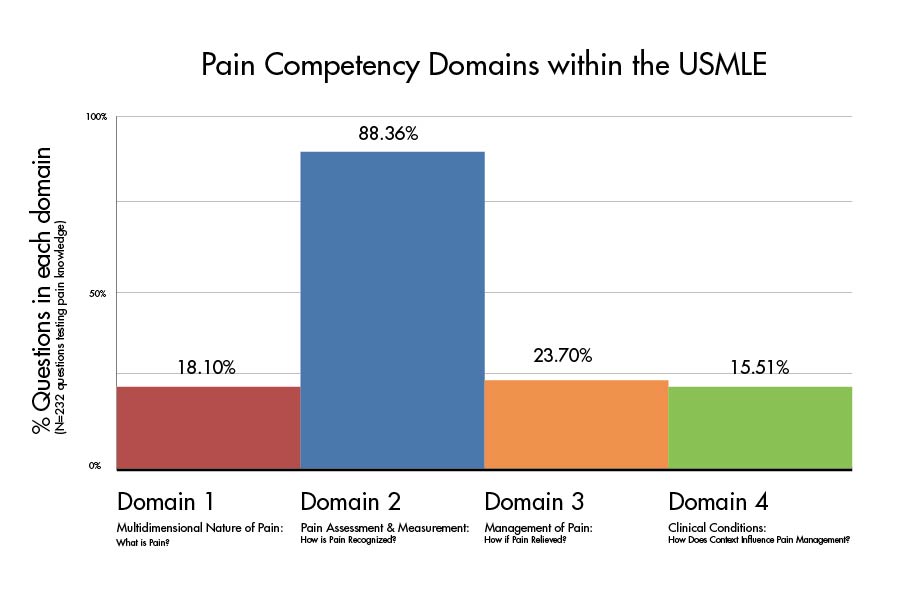

The method of organization they developed at the summit breaks down pain knowledge into four domains: Multidimensional Nature of Pain: What is Pain?; Pain Assessment and Measurement: How is Pain Recognized?; Management of Pain: How is Pain Relieved? and Clinical Conditions: How does context influence pain management? Each domain is then broken down into more specific competencies.

The 2018 analysis of pain-related questions on the USMLE used these core competencies to organize and keep track of where the exam’s questions were focused. After a group of raters in secure conditions reviewed 1,506 questions from four randomly selected exams, it was discovered that 28.7 percent of the questions included the word “pain.”

“At first I thought there would be fewer questions related to pain,” Young said. “For roughly a third of the questions to involve pain is quite significant. It was nice that pain was there, but what stunned me was the fact that almost 90 percent of the questions only focussed on assessing and recognizing pain rather than on managing it.”

The results showed that 88.4 percent of the pain-related questions fit into Domain 2, focusing on how pain is recognized, with only the remaining 11.6 percent of the questions focusing on the treatment, context and nature of pain.

“We discovered that pain was all over the test, but largely as a descriptor,” Fishman said. “The test reflects the bigger problem. We raised awareness about pain and taught doctors to recognize pain but not how to safely treat it.”

Both Fishman and Young said that that they were pleased to have been granted access to the usually confidential exam forms. Fishman added that he hopes the findings will help to catalyze tangible change in pain education, starting with changes to the USMLE.

“This study is really the first of its kind,” Fishman said. “The test has committee after committee looking at it and modifying it every year, but has never had an outside group. I’m sure that the USMLE will be revised based on our findings.”

The USMLE is produced by the National Board of Medical Examiners, based in Philadelphia. The NBME’s interim communications director Luise Moskowitz discussed the process of how the exam is written and annually reviewed in committees composed of hundreds of scientists, physicians and medical educators from across the globe.

“All ‘item writers,’ as they are called, receive item writing training by NBME before they do work as part of a committee,” Moskowitz said. “The questions are vetted again by an internal review committee, made up of content experts who are also among our most experienced item writers, before being finally approved for inclusion on the USMLE. Existing questions are also regularly reviewed to make sure they are still relevant and accurate.”

Moskowitz also noted that she thinks the UC Davis study will cause some changes to be made in how the test deals with pain.

“As for the [Fishman 2018] pain management study specifically, recommendations were generally favorably received and most of the topics they recommended will be incorporated into future item writing assignments,” Moskowitz said.

Despite the thorough and rigorous USMLE question writing and review process, outside researchers were able to make discoveries about the content of the test of which the NBME was not previously aware.

Fishman’s 2018 study operates under the premise that identifying areas in which the competency level demanded of medical students is lacking is an effective way to tackle the opioid crisis. Young said that she is surprised at how frequently people are quick to simply identify opioids themselves as the biggest part of the problem without looking further “upstream” at other factors, like how medical students are conditioned to conceptualize, recognize and manage pain.

Young acknowledged that even with reforming pain curricula to better reflect the core competencies, there are still additional challenges that can make it difficult to solve the opioid epidemic.

“Big pharma has had a lot of power over the years with so much marketing to doctors and patients,” Young said. “I think people deserve to have knowledge about possible medications, but I think it’s an industry that clearly needs to be looked at every step of the way.”

Young also explained that not every patient’s pain is best treated with pharmaceuticals.

“Sometimes people will think that medications are the only things that can help them, but we are now seeing the benefits of other forms of treatment, like biofeedback therapy,” Young said. “Pain gets in the way of people being able to do their daily life. Often, people who are in a lot of pain are also quite depressed and [pain and depression] can feed each other, so it can be difficult to know which one to target.”

From speaking with her coworkers, Young has learned that it can be difficult for physicians to properly identify and treat patients.

“I know from colleagues that it is very frustrating when you see someone in pain and you don’t have the tools to help them,” Young said. “Pain tends to slip through the cracks. Knowing how to deal with people who are in pain is so important because almost half of the people who come to a hospital emergency room are there because of pain.”

Young discussed some of the solutions that she hopes will help tackle the problems associated with poor pain education.

“We’ve been developing learning activities to practice working with a team and doing assessments and develop a strategy to manage the pain,” Young said. “For example, there are situations when patient’s pain may be better addressed if the issue is also brought to a psychologist.”

Young also explained how consulting with specialists in other areas has had many benefits in the process of developing better guidelines for teaching pain competency.

“We have had help from people from the vet school to better understand non-verbal communication,” Young said. “This can be crucial with patients who have trouble communicating the nature of their pain, like with people with dementia.”

Allowing medical professionals with different areas of specialization has been an effective way to address existing knowledge gaps. Dr. David Copenhaver, the director of cancer pain management at UC Davis, facilitates Project ECHO (Extension for Community Health Care Outcomes). For a little over four years, this program has been conducting video mentoring sessions every week, connecting with about 30 clinics across northern California.

“Project ECHO is a program originally out of University of New Mexico,” Copenhaver said. “A physician who was a liver specialist there essentially wanted to work himself out of a job, so he developed a telementoring program to teach others what he knows.”

The idea of “working oneself out of a job” reflects the goal of the program, which is to increase the number of people with specific competencies.

“This study on the USMLE validates the idea that there is awareness of pain, but that we never taught anybody how to treat it,” Copenhaver said. “Most medical schools currently devote little time to pain medicine in early years of medical school. This changes the landscape because you can offer better access and more care [and] teach other people to become pain experts.”

Copenhaver explained why he thinks it’s so important for people to be more knowledgeable about pain in order to avoid over-prescribing pain medications.

“In addressing the opioid crisis, one of the things frequently suggested is to just prescribe morphine products more responsibly, but this often translates to just not prescribing it at all, leaving patients without a solution for treating their pain,” Copenhaver said.

In order to avoid these situations and to ensure that the next generation of medical professionals becomes proficient in the core pain competencies, Fishman and Young think that there must be top-down rather than bottom-up change. They expressed their thoughts on driving change in pain education by co-writing a journal article on the topic in 2016.

“Testing competency in pain management is not part of the fundamental examinations required by state agencies for the licensure of health professionals,” Fishman and Young wrote.

Because of this fact, Fishman and Young argue that more educational institutions and medical bodies need to endorse and adopt their core competencies so that they can be enforced from the top down.

“If the external bodies that regulate and direct curricular requirements of professional health schools adopt these goals, then they will be integrated into the curriculum at each health science education institution,” Fishman and Young wrote.

They also argue that there must be some form of accountability to ensure that medical students meet the pain competencies.

“Schools must know that graduates without competency in pain management will struggle to pass their boards and become licensed professionals, as well as jeopardize accreditation for their program or institution,” Fishman and Young wrote. “Individual schools or programs will design their own educational content, training methodologies, and assessment methods as they strive for institutional accreditation, and individual certification and licensure of their graduates.”

Fishman, Young and Copenhaver all made it clear that they think pain is not a topic that can simply be taught thoroughly in a course or two; it needs to be taught alongside all other subject areas.

“It’s about making sure pain is spread across the curriculum,” Young said. “Pain presents different challenges in different contexts.”

Written by: Benjamin Porter — features@theaggie.org

There’s certainly a great deal to know about this subject.

I like all the points you have made.