How design might help the opioid crisis

Depression. Migraines. Broken bones. Pain can take many different forms. When one considers the ways in which age, gender and culture can affect the perception of an individual’s pain, it can be very difficult to communicate effectively what they are feeling. This is especially true for those who suffer from chronic pain. Often without a cure, their primary recourse is to manage their condition with painkillers, such as opioids. Just last year, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services declared a public health emergency about the widespread misuse of opioids.

If there’s an epidemic of opioid misuse stemming from pain, the question that arises is: how do we effectively talk about the crisis when we struggle to communicate about the pain we are feeling to begin with? This is the question that drove the team at the UC Davis Center for Design in the Public Interest to create “the pain project”. Using what they call “democratic design,” a process akin to dialectical problem solving, the interdisciplinary team of designers, computer scientists and writers work in concert with doctors and clinics to address medical needs through clear information design.

“We begin with really trying to get to what is the coordinate, like what is the issue and what is the need?” said Susan Verba, an associate design professor at UC Davis and lead designer behind DiPi. “Working with the doctors in a number of meetings, we try to ask a lot of questions and think together. We then propose some possible solutions, hear their responses and then further evolve the idea.”

The physicians at Hill County Health and Wellness Center began this process by designing a product that would effectively present alternative treatments to opioids for patients’ consideration. One product the team settled on was a poster that, in plain text and simple ideograms, presented 16 possible paths a patient could take. But this was just one form the idea took.

“We take content, like the poster, and we play with the form, because every patient is different, and different things work for different patients,” said Zoe Martin, a design student and DiPi member. “We turned the poster into cards, and there’s a video that they can watch if that communicates better with them.”

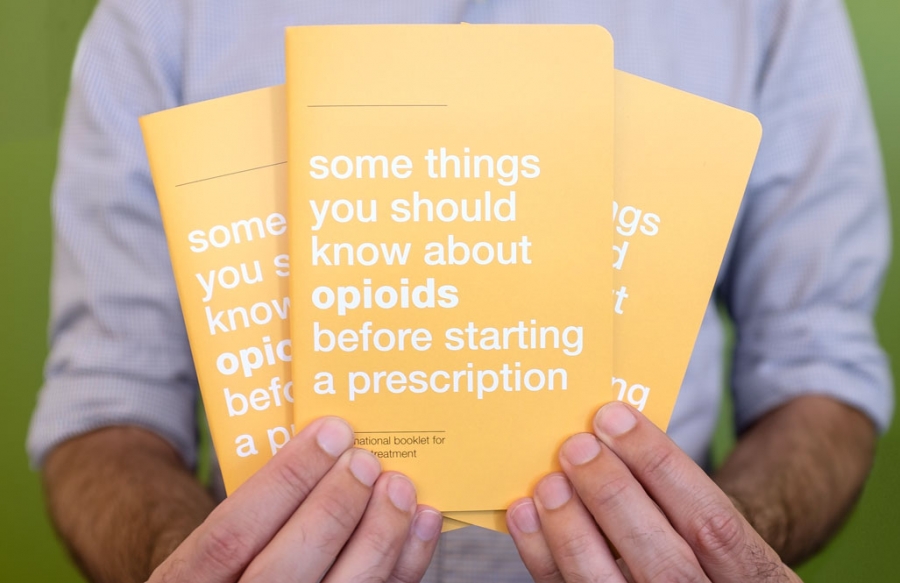

In simple language and images, the video informs viewers of the various pros and cons of individual opioid treatments. A booklet was made to accompany the video, in case patients have limited access to the internet. Another booklet helps patients taper off opioids or other painkillers if they are addicted. The newest booklet is about properly addressing a situation in which someone has overdosed on painkillers.

Accessibility in any form might be the defining element of DiPi’s design philosophy. It is not surprising, then, that they have addressed the complicated language of medical forms that might make it intimidating or challenging to visit the doctor. More than simplifying and making the language clear, the documents are made to be more visually engaging. A good example of this is their redesign of the pain-treatment folder from the Hill County Health and Wellness Center to an easy-to-read comic strip.

Translation is also a huge issue in receiving accessible and proper medical care, especially in California, where Spanish is spoken by nearly 40 percent of the state’s population.

“Whenever I look at medical literature, it’s never translated for the average person, nor is it ever translated for Spanish speakers, which is like such a common language in California, and it frustrates me,” said Hannah Hill, a student in the Textiles and Clothing Department and a project support intern for DiPi. “So I thought it would be great to get involved with DiPi and help make their material even more approachable for even more populations.”

DiPi is currently working on translating its designs into as many languages as possible. It will continue working with medical professionals to create more accessible and effective modes of communication between doctor and patient.

“Usually designers are at the tail end of the process and they’re asked to come in and give form to other people’s content,” Verba said. “You can’t have the kind of impact you’d like to have [as a designer] and you can’t learn as much as you’d like to learn by loading up other people’s problems. So that’s what we really try to do here is flip that inside out and say ‘Hey, yes, we’re not doctors, but we have something to bring to the table.’”

While DiPi does not provide answers to the opioid crisis, it is offering useful and creative means to help mitigate the severity of it by making medical treatment more accessible and clear to larger populations.

Written by: Matt Marcure — science@theaggie.org