Showcasing prestigious academia

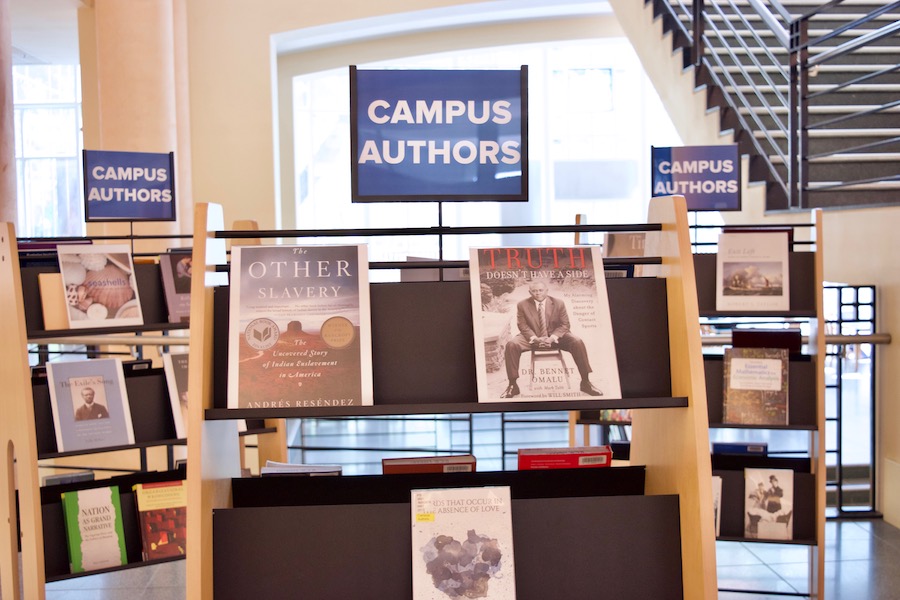

On the first floor of Shields Library, there is a small display of books written by UC Davis faculty. Hailing from disparate disciplines, many campus educators publish books in addition to their journal articles, research and teaching. Professors Julia Simon of the French and Italian Department, Andres Resendez of the History Department and Donald Palmer of the Graduate School of Management have each published more than one book thus far in their careers. They can each speak of the connections and transitions between publications, the challenge and satisfaction that is publishing, not to mention the work at hand.

Professor Simon narrows her research to the 18th century while broadening its scope through interdisciplinary work. One of Simon’s primary lenses is music, to which she has personal ties, having gigged in a jazz band for many years. Simon published a book entitled “Time in the Blues” and is currently working on her fifth book, “Debt and Redemption.”

“I got interested in the idea of teaching blues since I play it all the time,” Simon said. “First, I did a first-year seminar, freshman seminar, and that went really well. Then I developed a big humanities course on it, so I do kind of a cultural history of the blues. I gave a talk at an American Musicological Society conference and it went really well and I was like, ‘I could publish an article on this.’ So I wrote an article, and I published it and then I thought, I have an idea for a book, and I’m just going to do it.”

That creative spark became “Time in the Blues,” a book about the historical realities that gave particular form to the blues music of the era, the way that these realities impacted individuals experiences of time and how that time is expressed and felt in blues music. Simon makes these realities tangible.

“A lot of the argument in time in the blues is about how things like sharecropping, or long prison sentences and even convict lease […] how that might change your perception of time,” Simon said. “How you might not be connected to your past, how you might not be able to project into the future because things are foreclosed and why the music that you play might be so focused on the present.”

Furthermore, Simon considers how and where music is born in the first place, connected inextricably to the resonance it may have with present and future listeners.

“It really makes you think about how music comes to reflect the world around you,” Simon said. “I think about how blues came about in the 1890s when race relations were really at their worst in the United States. It’s when lynchings were at their peak, when Jim Crow laws were being put in place. I think one of the things that the book does do is make you think about those things, when you listen to a song, what exactly happened.”

While Simon’s familiarity with playing as well as studying music elevates the book as theory, she believes it can be relevant to the UC Davis community that appreciates music. “Time in the Blues” serves as fertile grounds upon which one can interrogate the kind of music with which they resonate.

“Maybe students would be interested to think more about what they like and why they like it and what gave rise to it,” Simon said. “At the end of the book, I talk about how you can go listen to people play blues and it can kind of sound, we call it phoned-in […] but those ones that really get you, I say in there, I think it’s because people really understand where it came from.”

Professor Andres Resendez is not new to publishing, much like Simon, and similarly finds that the research from one book project propels him into the next. His book displayed, “The Other Slavery,” informs readers of the history of Native American enslavement both by one another and by colonizing forces.

“Indian slavery, unlike African slavery, was forbidden early on,” Resendez said. “The Spanish crown prohibited the enslavement of Indians under all circumstances as early as 1542, so very early. But by that point European colonists essentially depended on coerced Indian labor for everything.”

Distinguishable from the enslavement of African Americans in the United States by its illegality, Resendez finds a number of differences that obscure the realities of Native American slavery over the course of history. He believes these factors are at least partially responsible for the ignorance of many to this story.

“I think one of the reasons why we have a hard time coming to terms with this other slavery, as I call it is because A) it goes by very different names, B) it was supposedly was not supposed to exist and there are other reasons. For example, African slavery involved the wholesale transfer of millions of people across the ocean, and therefore we have a lot of these port records. Indian slaves in contrast were both procured and consumed in locally or regionally and so […] it’s very hard to come to terms with hard evidence by way of numbers, for example.”

In addition to formulating an estimate of the number of Native Americans impacted by a period of slavery between Columbus and the 1900s, Resendez also wants to step away from an ideology of victims and victimizers, with the hopes of inspiring debate and scholarship among researchers.

“One of the things that I tried to do in my book […] is to point out that this is not a history about victims and victimizers,” Resendez said. “Everybody who was in a position to do it, did it. There are a few groups that, because of their particular conditions, did not benefit from the enslavement of other Native Americans, but everybody who was in a position to benefit from this did it. This is not a history about pointing fingers at some people or others but it’s more about human nature.”

By human nature, according to Professor Palmer of the Graduate School of Management, we also live within organizations. This is the focus of Palmer’s research: abuse and alternative value systems generated by organizational cultures. Palmer wrote “Normal Organizational Wrongdoing,” which inspired the Royal Commission of Australia to seek him out to conduct a report on abuse within the country’s institutions.

“My book is called ‘Normal Organizational Wrongdoing’ and the most basic argument in the book is that misconduct is common,” Palmer said. “The other thing about my book is that the reason it’s prevalent is that every structure that makes organizations what they are […] can both make them efficient and effective but can also, if they’re misaligned, lead to misconduct. Insofar, as we all spend lots of time in organizations in our lives, it’s good to understand […] how organizations can cause people to engage in misconduct, even if they are ethical, law abiding rule following order obeying people. We’re all at risk of that. The consequences can be really severe.”

Palmer explained how ‘normal’ people become party to misconduct as part of organizations that require or teach alternative knowledges of them.

“Organizations are many things,” Palmer said. “They are administrative systems, they have rules and protocols, they are power structures […] but one of the things they are, in addition to those things, is cultures. They have a set of assumptions about the nature of the world, and values and beliefs, about what’s good and what’s bad and norms about what to do. In some cases those cultures have a lot in common with the, what you might call a societal culture […] and in other cases they’re really very different. Some of it has to do with the kinds of people who are recruited, some of it has to do with how people are socialized once they enter the organization. There are multiple things going on.”

Palmer applies his research expertise to the case of abuse in Olympic gymnastics.

“In the Olympic sports domain, the assumption is that the children are just small humans,” Palmer said. “One way that’s manifested is they’re referred to as athletes. Once you have a universe where these twelve-year-olds are just considered smaller versions of adults, you can understand why coaches would end up in inappropriate relationships with these kids, because they don’t see them as children.”

Given the commonality of misconduct, Palmer felt that more writing needed to be published on the phenomenon within organizations. As a teacher of management courses, the absence of materials was palpable.

“The book was something like an itch that I wanted to scratch,” Palmer said. “I had taught a course, ethics, social responsibility and misconduct at UC Davis for the graduate school of management, and I just couldn’t find anything which seemed to accord with what I was reading in the Wall Street Journal or the Washington Post. I kept on thinking, there’s a really obvious way to approach the subject, but I haven’t seen anybody who’s done that. So I did write a journal article, and I would give talks, and I kept on expecting somebody somewhere to say, ‘you know somebody’s already done this.’”

According to Palmer, that ‘somebody’ never arrived, and he took up the project. Since “Normal Organizational Wrongdoing” he has also published “Organizational Wrongdoing: Key Perspectives and New Directions” and “Comprehending the Incomprehensible: Child Sexual Abuse in Organizations, An Organization Theory Perspective” alongside Valerie Feldman.

Palmer, Resendez and Simon each seem to relish the experience of crafting a book as a necessary output of their research interests. However, the privilege of spending three or four years with one project may not be accessible to junior, or adjunct, faculty.

Simon noted that the publishing process requires the writer to essentially finish the book without a commitment from the publisher that they will accept it, leading to a prolonged period of crafting and revision.

“Publishing books is a tough thing, it’s a really tough business. You essentially have to finish the book before you even go out and find out if there’s a publisher. Books get rejected and then you start all over again, it’s just crazy. It’s a slow and difficult process, but obviously we love it or else we wouldn’t be doing it.”

Written by: Stella Sappington — features@theaggie.org