Find out what makes this clip so ambiguous and why some hear one, the other, or both

Yanny vs. Laurel is the dress debate 2.0. A couple weeks ago, the internet nearly broke (again) with the controversial Laurel/Yanny debate.

The audio clip was discovered by a confounded high school student upon searching “laurel” on Vocabulary.com for a school assignment, according to Wired. The word means a “wreath worn on the head, usually as a symbol of victory.” However, when the student listened to the audio clip for the word, she heard something very different.

After hearing Yanny over and over, the bewildered student shared the clip on social media, which was later shared on Reddit and went viral. Thus the Laurel/Yanny squabble was born.

“It’s like one of those visual illusions, is it two faces or is it a vase?” said Santiago Barreda, an assistant professor in the Linguistics Department. “It’s like that, it’s just an ambiguous sound that you have to make a guess.”

Barereda’s research focuses on the roles of the listener and how language is perceived. Given the relevance of the Laurel/Yanny phenomenon, Barreda has made this a discussion topic in his phonetics class (LIN 112).

“It’s from a dictionary website, from a hired voice actor’s pronunciation. Whoever made the website considered this to be the canonical, perfect English,” Barreda said. “So obviously they thought it wasn’t ambiguous, the reproduction is ambiguous because of poor recording, basically.”

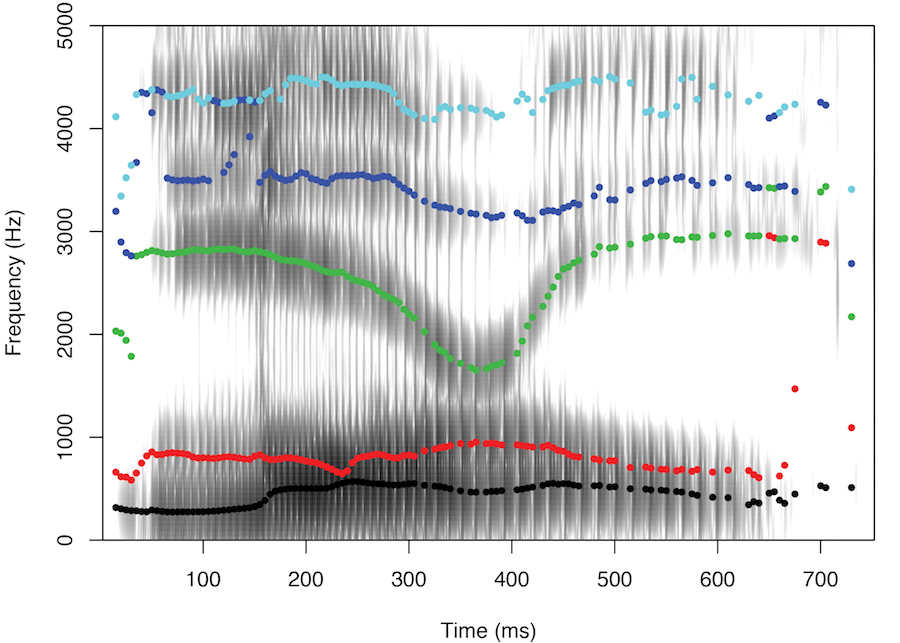

One of the predominant reasons for the controversy is the quality of the audio clip and the quality of the computer or phone speakers people are tuning in on, Barreda explained. When the clip was re-posted on various sites, the original clip was distorted, causing alterations in the sound frequencies.

“It’s like if you took a picture of somebody, and then if you took a picture of a picture, and then a picture of a picture of a picture,” Barreda said. “It’s a messed up recording. If you hear the original, there is no ambiguity. It’s from a dictionary website, the original is not remotely ambiguous.”

Another theory floating around the internet for this auditory paradox regards the hearing ability of the listener. Our hearing ability naturally deteriorates with age, and over time, we struggle to hear higher frequency sounds. However, our hearing can also be damaged by exposure to enduring, loud noises. Examples of this include planes, playing music through headphones at an elevated level and concerts.

“It’s just a normal process of aging that we lose higher frequency resolution as we get older, so we can describe it as a physiological property of the cochlea,” said Georgia Zellou, an assistant professor in the Linguistics Department. “The cochlea is the membrane in our inner ear and due to the way it is anatomically, the part of the cochlea that has really high frequency, resolution above 6,000 or 7,000 or 8,000 hertz, naturally loses its ability to function as well as we get older.”

The contested idea is that the level hearing damage one has endured could determine whether they hear Laurel or Yanny. But this is not true according to Barreda. Although frequency is a factor in whether one hears Laurel or Yanny, high frequency hearing loss or damage will not affect the listener’s interpretation of this internet sensation.

“High frequency hearing loss is real, but it’s above the 10,000-plus hertz region, which is a very high frequency,” Barreda said. “I’ve never heard of anyone having significant hearing loss or high frequency damage below 5,000 hertz, and this audio clip is below 1,000 hertz. High frequency hearing loss can’t explain this at all.”

The role that frequency plays in this paradox is not the cochlea’s ability to detect it, but whether the individual listener pays attention to higher or lower frequency sound. The New York Times published an interactive tool which amplifies both the higher and lower frequencies from the original audio clip.

“Here is what’s really interesting about it, if we look at all the sounds sequentially, starting with ‘L(uh)’ and ‘Y(uh)’, in English those are really distinct, discrete sounds,” Zellou said. “Even acoustically, if we look at the phonetic signature of the two sounds, they are very distinct.”

By dragging the scale back and forth on the interactive tool, the alteration of the frequency makes certain sounds more prominent.

“[Luh and Yuh] are still similar, for both our mouths are somewhat open. They are sonorant sounds where we are creating louder sounds than other types of sounds we might make,” Zellou said. “So ‘L(uh)’ and ‘Y(uh)’ have certain similar properties articulatorily and thus acoustically.”

However, the act of hearing is not just a physical process. To ascribe meaning to language, we must use cognition.

“We use speech to communicate language, but speech is ambiguous,” Zellou said. “Everytime I produce a word, you don’t know if that was the exact message I intended in my head. This process of trying to translate this acoustic message is always going to be probabilistic. It’s always going to be a guess to some extent.”

This introduces a cognitive dimension. In play is not only the physical frequencies of the sound and the physical nature of our ears but the way our brain draws connections between sound and meaning.

“But language exists as these discrete categories in our mind, categories of sounds, a ‘Y(uh)’ versus a ‘L(uh)’, categories of words that exist because we have heard them,” Zellou said. “One thing that could be biasing people towards Laurel in certain situations is maybe the fact that Laurel is an actual, true word that exists in American English. Whereas Yanny is not, it’s what we call a nonword, it’s not a word that we use in American English at this point.”

The evidence that this is not purely a physical phenomenon, such as hearing ability and speaker quality, is that some individuals can hear both Laurel and Yanny from the same recording.

“It can’t be purely about the anatomy and or the properties of someone’s hearing resolution, I think there is also a really strong cognitive factor involved,” Zellou siad. “I have heard of these anecdotes of people who are listening to it on repeat and getting the different precepts within a single sitting. So for me that is evidence that it can’t be purely physical.”

Wafaa Yazdani, a third-year economics major, and Sonia Aamer, a second-year biochemistry major, had similar experiences.

“First I hear Yanny and then I heard Laurel, and then I heard Yanny again,” Yazdani said.

Most who heard the clip were polarized, hearing one or the other and creating an uproar on social media, much like the dress debate in 2015. But the fact that some individuals can hear both is evidence that it is a combination of several physical and cognitive factors.

“I heard Laurel first and then later on in the day I told my friends about it and I played it again, and I heard Yanny,” Aamer said. “It really tripped me out, I felt like something was wrong with me.”

The ambiguous nature of this audio clip and the many factors at play caused this sensation, possibly resurfacing unresolved feelings from team black and blue or white and gold.

“I don’t think it would’ve been as big of a deal if people were only hearing one, since you hear both at different times, I think that is what got more hype,” Yazdani said. “I still can’t tell which one it is, it’s different every time for me.”

So, which one did you hear?

Written by: Grace Simmons — features@theaggie.org