Researchers have found a drug that can help prevent cancer from returning after chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a paradox. It kills cancer cells but once the treatment is completed, it makes it easier for tumors to re-grow. Researchers at Harvard and UC Davis demonstrated in a paper published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that the leftover cell debris from chemotherapy can encourage tumor growth. The good news is that a novel drug developed at UC Davis might help mitigate the pro-tumor environment and improve health outcomes for chemotherapy patients.

Today, doctors have many tools to kill tumors, but it is almost impossible to eliminate every single cancer cell. In 70 percent of ovarian cancer patients treated with chemotherapy, cancer returns after treatment. The researchers found that cancer cells can more easily regrow after chemotherapy by taking advantage of the body’s response to the increased cell debris.

“The chemotherapy will kill the ovarian cancer, which is good news, but the bad news is that the leftover dead cells can stimulate the leftover living cells.” said Dipak Paigraphy, a professor at Harvard University and an author of the paper.

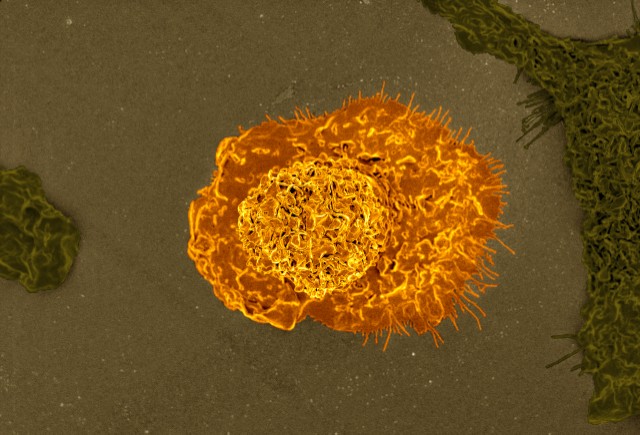

Special cells called macrophages clean up debris in the human body when cells die. After chemotherapy, there is so much debris that the macrophages call for help by releasing signaling molecules called cytokines. These cytokine signaling molecules initiate inflammation, a common biological response where increased immune system resources are sent to a damaged part of the body to help clean up and promote regrowth.

“The body says, ‘something is dreadfully wrong, I’m going to turn on a bunch of chemicals that I make in my body and try to survive the insult,’” said Bruce Hammock, a professor of Entomology and Nematology at UC Davis and an author of the paper.

In cancer patients, however, this inflammation can promote the re-growth of remaining cancer cells instead of normal cells.

The research team realized that if they could modulate or control the release of the signaling molecules that promote inflammation, they could reduce the chance of cancer returning after chemotherapy.

The researchers used drugs that block the creation of the signaling molecules. In the body, special proteins called enzymes facilitate chemical reactions. A special enzyme called Cyclooxygenase-2, also known as COX-2, is responsible for producing many of the components of the signaling molecules, including the cytokines that the researchers wanted to control. Many off-the-shelf drugs like aspirin and motrin work by inhibiting this enzyme. In this project the researchers turned to a novel drug called PTUPB, which was developed at UC Davis by Sung Hee Hwang.

According to Jun Yang, a researcher in the Hammock Lab at UC Davis, the PTUPB drug blocks the COX-2 enzyme as well as another enzyme called sEH that also produces the components of signal molecules.

“The PTUPB is blocking the COX-2 enzyme and the sHE enzyme,” Yang said. “It’s blocking the way to transfer from the substrate to the product for both enzymes.”

PTUPB is a molecule that physically interrupts both enzymes and prevents them from producing the lipids that are the building blocks of the cytokine signalling molecules. Without the signal molecules, there are no messengers to raise the alarm and cause the inflammation that promotes the growth of tumor cells after chemotherapy.

The research team, led by Alison Gartung at Harvard, studied the effects of PTUPB on mice in the laboratory. They found that mice with cancer that were given PTUPB before chemotherapy had substantially better outcomes than mice who were just treated with chemotherapy.

According to Bruce Hammock, the PTUPB treatment looks promising.

“Ovarian cancer is particularly difficult because it’s so hard to get rid of. So the data from these studies in mice look really good,” Hammock said.

The researchers plan to continue testing the drug and eventually bring the drug to the public to increase the effectiveness of chemotherapy.

Written by: Peter Smith – science@theaggie.org