Du Bois’s social theory weaves itself in and out of Peele’s sophomore film

Spoiler alert: This article discusses “Us” and therefore reveals information you may not want to know if you haven’t watched the movie.

Jordan Peele’s “Us” is internationally applauded as an uncanny horror film that deals as much with identity dissociation as it does with America’s disturbing past. In his sophomore release to the film “Get Out,” Peele once again proves to be a master of the genre — inadvertently breaking the mold of horror and setting a precedent for future filmmakers.

Coming in at a 94 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, thereby certifiably “fresh,” it’s obvious that those who disliked the film may not have understood it. From the high-quality performances by its actors to its bone-chilling score, there is so much to marvel at within the reel. More so, there is much to be learned from the film by way of its blatant metaphors and social allegories. Specifically, but not limited to, the embodied social theory from the first African-American doctortorate recipient: W.E.B Du Bois.

There have been numerous articles written on the subject of Peele’s “Us” and Du Bois’s theories; many of them go much deeper than simply analyzing the facts that marry the two together, and instead highlight Peele’s entire career as a filmmaker and social activist. But it is imperative to focus in on the idiosyncratic details that go into Peele’s latest film. They not only highlight Du Bois’s theories, but bring audience members to craft their own theories about the satirical movie they live in— the United States of America: where a political climate can still exist that seemingly functions through racial colorblindness.

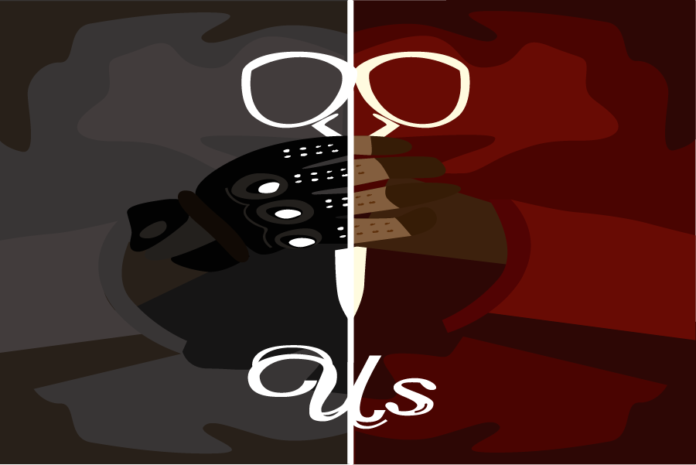

Even before the start of the film, movie-goers will know that “Us” deals with double consciousness, even if they can’t say exactly what double consciousness is. The movie poster that features Lupita Nyong’o holding a smiling mask of her face halfway off of her actual, petrified face offers a brief look at the duality that subsists within the film.

Before starting to pick apart key details of the film and splaying them out amidst the backdrop of Du Bois’s theory, it’s vital to first hear a quote from his most famous works, “The Souls of Black Folks.”

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Though I tread lightly in explaining Du Bois for fear of botching this immortal-omniscient philosophy, the theory of “the double” goes something like this. The double consciousness is the phenomenon of having one’s consciousness divided into several parts, making it impossible to have one unified identity. Du Bois primed this theory within the context of race relations in the United States. Since black Americans have lived in a society that has historically oppressed and devalued bodies of color, it is difficult for them to unify their black identity with their American identity. Therefore, “the double” asserts that the black community is forced to cultivate their own unique perspectives — their African heritage — while also having to visualize themselves through a lens of how they might be perceived from the outside world (i.e., America). This creates a psychological struggle to reconcile their identity as a person of color and as an American citizen — “two warring ideals in one dark body.”

Now, look to Peele’s film and see the endless symbolism that embodies Du Bois’s theory. Look deeper at the poster, besides the obvious duality of the mask. Nyong’o’s character, Adelaide Wilson holds a pair of scissors: two knives conjoined together by one thin metal peg.

Then there is the Michael Jackson glove on Wilson’s right hand, which Peele, himself, mentions as a tribute to his influence. Later in the movie, the audience will see another shout-out to Jackson by way of Adelaide’s “Thriller” shirt in an ‘80s flashback, which is certainly not a coincidence.

“Everything in this movie is deliberate, that is one thing I can guarantee you.” Peele said in an interview, “Michael Jackson is probably the patron saint of duality […] the duality with which I experienced him [Jackson] in that time was both as the guy that presented this outward positivity, but also the ‘Thriller’ video, which scared me to death”

Evidently, there is more to the duality of Jackson that expands beyond the context with which Peele explains— one that exemplifies the racial backdrop of Du Bois’s theory.

Further into the heart of the film, the audience meets the antagonists: a group of doppelgangers who are required to live beneath the earth’s surface in hidden tunnels. The “Tethered,” as they are called, claim to be shadows of the bodies that function in the light of the American dream. Adelaide’s family, a group of middle class Americans enjoying a family vacation at the Santa Cruz Boardwalk, are psychologically tortured by their shadows and are forced to fight for their lives as the murderous Tethered attempt to replace them above ground.

This all seems to be evidence enough of Peele’s desire to highlight the themes of duality in his film, but the story takes a turn somewhere in the middle that would surely leave sociologists enthralled by the on-screen magic that ensues. When the Tethered corner Adelaide’s family in their summer home, they sit them down and explain who they are— “We are Americans” as Red, Adelaide’s doppelganger, says through a guttural voice. From there, Red forces Adelaide into handcuffs for the rest of the movie, causing her to fight off hordes of Tethered bodies while being partially handicapped.

Here we have it: Americans attempting to stamp out Adelaide’s family through the agency of a Tethered revolution that Red herself insighted in the shadow army. But the twists do not end there. Turns out that Red is actually Adelaide, and when the two first met each as children in a carnival attraction, The House of Mirrors, Red forced Adelaide into her shoes and into the tunnels where she spent the majority of her life while Red grew up in the comfort of Adelaide’s home. Therefore, who are the Americans and who are the oppressed? Which form of Adelaide started the revolution to retake the above ground? Is it the Americans who are attempting to stamp out the other, or the other attempting to take back what’s been stolen from them by the Americans?

Such answers can only be found by watching, and rewatching the film. Catching up on Du Bois’s theories will only help the viewer crack the code of Peele’s complex genius. As Adelaide still persists despite her oppressed stature by breaking free from the chains placed on her by Red and overcoming the American onslaught, she is forced into a position where she can only function through the confines in which “America” has placed her. Although she overcomes this bloody nightmare, she will never be the same. She can never forget the nightmare she was forced to endure.

Peele’s film is layered throughout. Even the title has a layer— is it only about the oppressed, or does “Us” include the oppressor? One thing is for certain, the statements made in this film will influence legions of moviegoers to think beyond the moving images on-screen. And with Peele becoming more active as a writer and director, all we have to do now is remain in the dark until he decides to once again shine a light.

Written By: Clay Allen Rogers — arts@theaggie.org