UC Davis researchers explore the role of metal in biological processes.

Metals like copper, zinc and iron are necessary for many biological processes. Oftentimes, however, when biologists study those processes, metals are controlled for or ignored because they are present only in trace amounts. For most research, this approach is warranted due to an inability to study everything. Yet the Heffern Lab in the department of Chemistry at UC Davis believes that thinking about the roles metals play in the body might be a useful framework to approach some difficult biological mysteries.

One such mystery involves the usefulness of a strange string of amino acids called c-peptide. The molecule is essential for the production of insulin, a key regulatory protein that controls how glucose is absorbed in the body. For a long time, researchers believed that c-peptide’s only role was to help with the production of insulin, but further research suggests that c-peptide plays other roles in the body.

“There is a bit of controversy over what c-peptide does,” said Marie Heffern, an associate professor in the Department of Chemistry and leader of the Heffern lab. “One of our hypotheses, is that part of why there is confusion is that metals are essential to its activity, and we are not taking them into account.”

Biological agents like peptides rely on cofactors, or “helpers,” in the body to function properly. The Heffern lab thinks that metals might be co-factors that allow the c-peptide to function.

To test this idea, the research team conducted several experiments to probe the relationship between the metals and c-peptide.

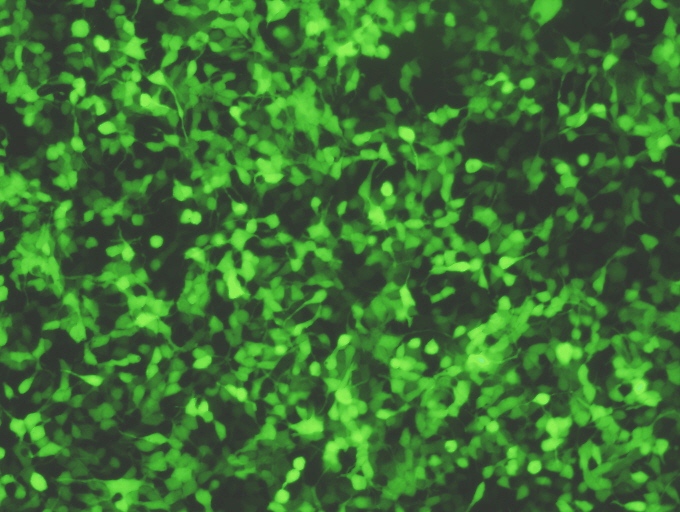

The team was curious to learn if the presence of metals would have any effect on the ability of c-peptide to enter cells through a process called internalization. They took different metals and combined them with c-peptide and then placed them around human embryonic kidney cells. They then measured how much of the c-peptide internalized and compared it with when there were no metals present. The researchers found that chromium and copper seemed to inhibit the ability of c-peptide to get into the cells.

“With chromium and with copper, there is a huge decrease [in internalized c-peptide] compared with apo [when the scientists just added the peptide without any metal],” said Michael Stevenson, postdoctoral researcher at the Heffern lab. “That is what led us to say let’s focus on copper and chromium.”

The team also used spectroscopy, another technique that involves shining light through the cell to find approximate stoichiometries, and explored possible inhibitory mechanisms using various other experimental techniques.

While the researchers were not able to definitively determine that metals are crucial co-factors for the action of c-peptides in the body, or explain the actual biological processes that peptides contribute to, they were able to determine that metals have some inhibitory influence on peptides. The new questions that have arisen with the information uncovered could be crucial.

“The study we have done is one of the few that actually tries to make a link between a biological effect and a binding interaction that is happening at a molecular level,” Heffern said.

Written by: Peter Smith — science@theaggie.org