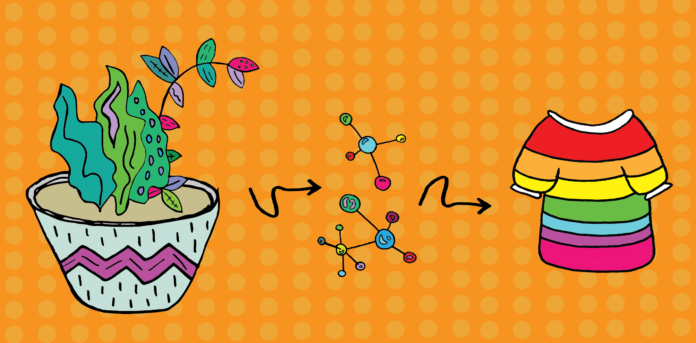

Synthetic dyes derived from plant material could encourage sustainability in the fashion industry

When thinking about sustainability and carbon footprints, it is important to consider society’s most polluting industry: fashion. The industry is responsible for over 10% of carbon emissions, more than air and sea travel combined, and is the second largest consumer of water. In addition, the use of petroleum-based synthetic dyes not only indirectly supports the continued mining of petroleum but also releases microplastics into the ocean. Inevitably, in taking steps toward sustainability, the issue of pollutive dying processes must be considered.

Professor at the UC Davis Department of Chemistry and head of the Mascal Research Group Mark Mascal and his team developed a method to derive synthetic dyes from plant-based materials while studying papers from the early 20th century that used a platform molecule called 5-chloromethyl-furfural (CMF).

“You can turn [CMF] into many value-added products. That’s the research the Mascal group has been focussed on in the past, probably at least a decade” said Jon Saska, a postdoctoral researcher at UC Davis and member of the Mascal Research Group.

The group has been studying CMF and its properties for a long period of time. It is their “trademark molecule” and they have demonstrated successfully that it can be used to make biofuels, monomers and specialized chemicals with pharmaceutical and agrochemical usages. The dye is a result of redoing experiments from the 1910s that the original authors never managed to truly characterize.

“We were able to reverse engineer what had happened,” Mascal said. “The compounds that were produced were deeply colored and that’s where we got the idea that, ‘Hey, these could be effective dyes!’”

Currently, the dyes are effective on synthetic materials and wool but not cotton, although potentially they could be altered to fix that. Originally the team only had three dyes, but currently there are five dyes within a red to yellow color range. The experiment they borrowed from only created a single compound of canary yellow crystals, so there is potential that with further research, a larger part of the color spectrum can be included in these dyes.

The dyes are still fully synthetic in nature. What separates them from the dyes in industrial use today is that they are bio-based and therefore carbon neutral, which means they remove as much carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they release, making them more sustainable.

“Just the fact that there’s awareness about it and that they’re trying to cut down one part of the problem in the dying industry, that’s great,” said Mathilda Silverstein, a fourth-year gender, sexuality and women’s studies major.

As of today, the dyes have not been put into commercial use, but there is potential. CMF is being produced at an industrial scale, which means a material essential in the production of the dye is readily available.

“We designed the reaction with [commercialization] in mind,” Sasak said. “Everything that is being used is relatively cheap, accessible, and effectively everything from the process is recoverable and reusable.”

Of course, theoretically, just about anything is completely recoverable and reusable. The molecule used to manufacture plastic bottles and polyesters, PET, could be 100% recycled if not for the fact that the process is expensive and requires a lot of effort. Although that specific benefit of these new dyes is debatable, it is still environmentally healthy in that it is produced from biomass. When dyes decompose, as all things do, and release carbon dioxide that will end up in the atmosphere, it is important that these dyes originate from a biological source.

“You have got to remember that it started out as natural carbon and it will end up as natural carbon,” Mascal said. “Those millions of tons of dyes will decompose to carbon, what matters is the source. Is it natural? Then it’s in a cycle. Is it petroleum? Then it isn’t. The problem with the use of petroleum is that you’re using carbon from ancient biological cycles. Everything should be used in its own cycle.”

By providing plant-based alternatives to the synthetic dying process, the Mascal Research Group is taking part in the initiative to reduce our carbon footprint and decrease reliance on petroleum.

If fashion is to remain essential to the modern lifestyle, it is important to take steps toward making it a sustainable industry.

“Synthetic dyes are relatively new, so using organic powder dyes could be an option, but the shelf life is shorter,” Silverstein said. “The best thing they can do is just keep trying to make better technology for this and keeping it more organic and plant-based. A lot of the companies that are using these harmful dyes are in Southeast Asia and South Asia and exploit their workers, and that’s unsustainable for the whole industry. If we’re focusing on sustainability as a whole, obviously we want safer dyes but we also want safer working conditions for workers and better factory practices.”

Written by: Husn Kharabanda — hkhara@ucdavis.edu