CCPA the first step in race to take back our data privacy

In 1890, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis called privacy “the right to be left alone.” But we live in a time where it is impossible to be left alone due to technology. Privacy in the digital age is difficult to even define.

Your degree of privacy depends largely on who you are. What may be private information for one person may not be private for another. For example, the home of former Vice President Dick Cheney does not show up on Google Maps — a privacy that most of us don’t have.

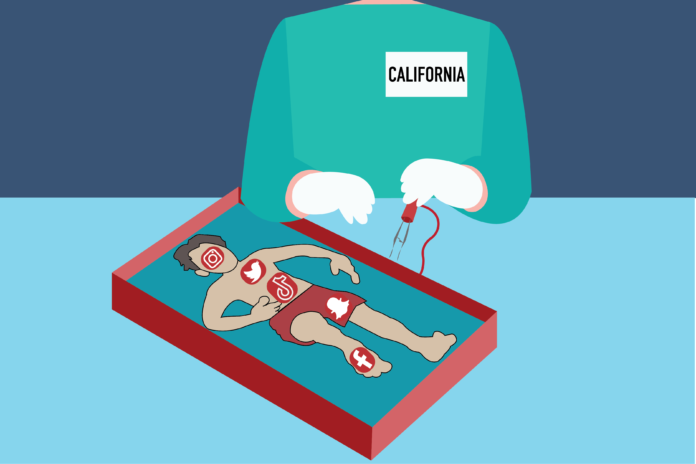

On Jan. 1, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) went into effect as the first major consumer privacy law in the United States. Its implications are yet to be seen, but it’s a crucial step toward figuring out what privacy is in this day and age and how we can get it back. The CCPA gives Californians the ability to own, control and secure their personal information that is collected by businesses and hold them accountable for the sale of users’ personal data.

Your data is worth millions of dollars to businesses, but exactly how much it is worth is unknown. Many of the companies buying and selling data still don’t know what to do with it yet, but we do know that our data (and metadata) can be used against us to change the way we think. Based on voters’ metadata, Cambridge Analytica claimed that they had developed psychological profiles of every American voter, allowing campaigns to target their ads directly to those most persuadable.

Our data is collected, assembled, analyzed and then weaponized to sell us products. Additionally, in trying to manipulate how we think, these products now include political candidates. This leads us to a question: How much of this manipulation do we want to allow in our society? In the other 49 states without a bill like the CCPA, theoretically, anything goes with user information — it can be sold and swapped to the highest bidder.

Our data is immensely valuable, and yet we don’t personally see any returns on its sale. The core economy of the online world is our data, and we don’t even understand its value. Luckily, there are those who would like to change that.

Senator Mark Warner (D-VA) introduced a bill this summer that will require social media companies to be transparent in how they are capitalizing on our data. Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) wants to implement a data tax that will punish companies that violate our privacy and sell our data. If companies are going to violate our privacy anyways, then we should at least be compensated.

Gov. Gavin Newsom agrees with this sentiment in the form of a data dividend. Given that almost all of us exist online in one way or another, a data dividend would act as a universal basic income, from which we could all stand to benefit. In the same way that Alaskan residents get a check each year for the extraction of oil from the Alaskan Permanent Fund, a data dividend could do the same for infinite digital resources.

An automated and tech-driven future that leaves humans behind is the fear of many, but a data dividend fund could ensure that those who will suffer the most in this future have a certain level of economic security.

California is leading privacy security in a way that the rest of our country needs to follow. As relentless users of social media, Americans need to win back our rights to personal and data privacy before it is too late. We need to have a better understanding of what should be private and what should be publicly accessible.

There is no way to avoid the data world completely. We have to be aware of the tradeoffs we face when we make digital footprints — it is not something we can opt out of anymore. But what we can do is force those in power to do something about it.

Our voices matter, as do these laws we vote on. Privacy must become a political issue across the country. We have a right and a duty to demand that our lawmakers change the rules of the game back in our favor.

Written by: Calvin Coffee –– cscoffee@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie