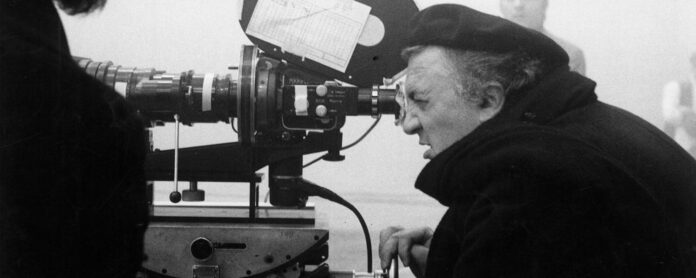

An ode to the director of “La Dolce Vita,” master of absurdism

Over the years, I’ve realized I’m a terrible person to watch movies with, which is especially problematic as someone who goes around calling themselves a “cinephile.” I can be prone to shouts and exclamations, but it’s at its worst when my excitement becomes incoherent. It’s usually Frederico Fellini, who would’ve had his 100th birthday late last month, that provokes this type of excitement.

Despite him being a director so ingrained in the canon of film, one rarely hears much about Fellini. Gone but not forgotten, the bellissimo of his work lives on, and a retrospective of both the man and his accomplishments are long overdue.

I first heard of Fellini from Adam Pfahler, the owner of the now-defunct but forever legendary San Francisco rental spot Lost Weekend Video. As one of the owners of the place, Adam seemed, to my 18-year-old self, the most knowledgeable man in the world when it came to cinema. He was also the drummer in a little band called Jawbreaker, which only added to his pedigree of “holy sh-t, this dude is sick.” Turns out, he was just a guy who really, really loved movies and had a passion for good art in any form.

I like to say I was employed at Lost Weekend exceptionally briefly, but in truth, I just hung out there a good amount in its last years on Valencia Street, painting cabinets and pretending to understand what mise-en-scene meant. Those were some of the best years of my life, and ones that I liken to a Fellini film — selfishly dramatic, beautifully absurd and, more than anything, indulgent.

I decided to jump back into things and throw on “La Dolce Vita,” a 1960 flick that was one of Fellini’s better known cinematic offerings, examining a journalist chasing the titular atmosphere throughout Rome. But immediately, I recoiled, for obvious reasons. The very act of “throwing on” something like “La Dolce Vita” was in itself already doing the film an injustice. I am aware of how much I sound like a first-year film major at NYU, but the point still stands — some of the beauty that comes with certain art is the circumstance one finds themselves in while engaging with it. Fellini, and “La Dolce Vita,” specifically, wafts with importance and demands precise attention.

You may throw on something like “The Office” or “Parks & Rec” while you deal with the malaise of everyday life. But that is exactly the opposite of the world in which Fellini lives. The opening scene of “La Dolce Vita” is a testament to this: We see a helicopter flying over Rome, the pilot getting distracted by a bikini-clad belle donne all while the helicopter transports a giant statue of Jesus Christ. The world Fellini constructs is one of surrealism, but one that avoids pretension — for the most part.

Instead, there is a freewheeling embrace of the absurd found throughout his work. Especially in “La Dolce Vita,” but deeply present in works like “La Strada” and “8½,” there is a love for the ludicrous, as well as the indulgent. In “Vita,” narrative structure is a reflection of this: seven distinct “episodes” are drawn for the viewer, with a prologue, intermezzo (intermission) and epilogue.

The inclusion of an intermezzo is particularly fascinating. Is it a stylistic choice to let the story flow, or a directorial decision made because the audience simply couldn’t keep up with Fellini’s perceived vision and needed a break from such a cinematic masterstroke? With Fellini, one finds that the line of self-importance is carefully drawn and sometimes overstepped.

But perhaps there is more insight here than appears at first glance. The chapter-esque structure of “La Dolce Vita” and other films like “8½” are eye-opening glances at how much Fellini’s work mirrors that of a storybook. Large swatches of characters, absurd situations and lessons layered throughout reflect the fable-like quality of Fellini’s films. Yet there isn’t anything childlike in his work, as most of his films have a run time of at least two hours and are shot in black and white with the aforementioned surrealism gleaming throughout. To watch something like that is to get lost in a world, one that is very much not about how things are but how things feel.

For a long time, I have been on a quest to find meaning. I believe most people in college are as well, whether they are conscious of it or not. Film is one of the things — like any art form — that will never fully explain things to you. Instead, it gives one a compass to go and find out on their own. Fellini is a director who ignited a love for absurdism in me, and he also shows that sometimes it’s okay and even encouraged to indulge. We are, after all, simply searching for the sweet life.

Written by: Ilya Shrayber — arts@theaggie.org