Assimilation through America’s favorite pastime

It was a bit of a long ride to the field, taking the better part of half an hour. When we got there, the smell of hops and yeast coated the field like a veil, courtesy of the Anchor Steam brewery across the street. The grass was deep green and the fog cleared, exposing a blue, cloudless sky. The man up to bat was large in stature and swung the stick like Thor’s hammer, thunder crackling as wood met leather. It was a line drive to me, the third baseman. My brain did a thousand tiny calculations. I stopped it, threw to second, got the force out and smiled. I never liked sports, but I sure as hell loved baseball.

The story of the American Jew is the tale of a constant struggle to assimilate, a perpetual othering while trying to accept whatever external culture comes your way. It makes sense, then, that there has been a long and storied history of the Jew in America’s favorite pastime: baseball. Speaking as a Jew myself, one of almost self-parodying levels, I have always seen the sport as a way to better understand the culture which I was born in and one the rest of my family has tried deeply to weave themselves into.

The first presence of Jews in baseball was during the ownership of Negro League teams in the 1920s — both members of the tribe and Black individuals were not permitted in the entirely White national baseball leagues, and the relationship they fostered became fairly symbiotic. With promotion from their Jewish benefactors, players in the Negro League achieved far reaching fame and better oppurtunities to play. The two groups relied on each other and worked together to operate in a system that rejected both of them.

In addition, the relationship between the Black and Jewish communities ran even deeper, especially when examining baseball legend Jackie Robinson. Much has been written about what Robinson did for baseball — most prominently the shift within Major League Baseball to eliminate race restrictions. Hank Greenberg, one of the first Jewish baseball greats, once collided with Robinson at first base during one of these groundbreaking games. What followed was a sheepish smile, with Greenberg whispering into Robinson’s ear, telling him that if he wanted to overcome his critics, he had to beat them in the beautiful game. Although narratives in sports are often dramatized in history, it seems like there was genuine support between Black and Jewish players, a direct result of their position in the sport.

There’s an old line my Semitic friends and I toss around whenever we get together: “It’s up to interpretation!” Born from a beginner’s Torah study class as a response to try to justify not understanding the text, we now say the line whenever we take the wrong exit or a waiter brings us something we didn’t order.

This is all to say that the flexibility of our central text is paramount to the Jewish experience. When speaking of baseball as a form of assimilation, this is particularly important.

In 1934, Hank Greenberg was one of the crown jewels of the Detroit Tigers, and the question of whether he was going to play on Rosh Hashanah, one of the holiest Jewish holidays, was central to many people both on and off the team. After meeting with a rabbi, Greenberg decided that it was fine, as the Torah does not technically forbid playing games on that day. Greenberg went on to win the pennant, and Americans began to rethink their opinion of Jews, rolling back some of their prejudices.

There are some things, however, that are very much set in stone. Thirty years later, at the first game of the 1965 World Series, Sandy Koufax abstained from playing. With people wondering what was going on, Rabbi Bernard Raskas of Temple of Aaron in St. Paul, sternly notified the public that everything was fine. Koufax was in the aforementioned synagogue, attending services. It was, after all, the first day of Yom Kippur.

It was a moment of pride for all American Jews, from the sunny sidewalks of Los Angeles to the smelly yet endearing subway of New York City. The fans, however, were a different story. The Los Angeles Dodgers, Koufax’s team, lost 2-0. The first game is often symbolic of the whole series but not always so. After losing a second time, they came back with a solid three-game sweep. Spirits were high. Koufax was looking sharp, but not sharp enough it seemed — the opposing Minnesota Twins clinched game six. Initiating a seventh meeting, the Dodgers, led by the southpaw pitching of Koufax, overcame the odds with a 2-0 victory. After this moment, Koufax was universally admired, and in 1965, the American Jew cemented a place in baseball history.

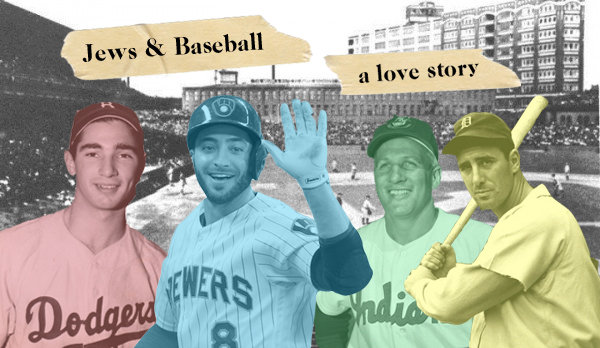

This isn’t to say there isn’t a Jewish presence in baseball today. The process of assimilation has run its course in many ways, with affectionate nicknames like “Hebrew Hammer” entering the sport’s lexicon. Ryan Braun, the Milwaukee Brewers’ left fielder, is perhaps the most well-known, along with Alex Bregman and Ian Kinsler from the Houston Astros and San Diego Padres, respectively. These guys, especially Braun, live up to the greats in many ways, compared to the likes of other Jewish all-stars like Al Rosen and Cal Abrams.

“It’s weird to me that there haven’t been more successful Jews in baseball right now, especially when you consider that many of them live in Los Angeles or New York,” said Ryan Cohen, a second-year communication major.

He went on to mention past legends.

“My family absolutely idolizes [Sandy] Koufax because he would never pitch on Yom Kippur,” Cohen said.

In many ways, there seems to be a reverence for the past. Past or present, for many, the Jewish presence in baseball brought a form of salvation, however small.

“In terms of sports, baseball was one of the few with big Jewish players, with the most idols to look up to, in a way,” said Noah Bennett, a recent graduate who studied environmental science and management. “It was so insane that people who have looked at us as weak or unathletic were suddenly rooting for us.”

Bennett spoke seriously, but paused for a laugh midway through our conversation.

“It was just good to see that,” Bennett said.

I stopped playing baseball after high school, content to throw around a ball with friends on the beach or at the park. I don’t watch games on television either — they don’t come anywhere near the excitement of being at a stadium, with a large order of Gilroy garlic fries, begging the concierge to let me onto the Coca-Cola slide. I follow the sport, but in a lot of ways, I look at baseball as a compass, one that was invaluable in helping me navigate a culture that was not my own. I’m sure for many Jewish players, professional or not, it is much the same.

Written by: Ilya Shrayber — arts@theaggie.org

You might be interested in the fact that in April 1945, two years before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers, a “try-out” was arranged with the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park for 3 stars of the Negro Leagues. They were Marvin Williams, Sam Jethroe AND Jackie Robinson. The event was precipitated through the efforts of a Jewish, Boston City Councilor named Isadore Muchnick. Rather than being the first team to integrate, the Red Sox were the last. It wasn’t until 1959 that Elijah “Pumpsie” Green was called up from the minors to play for Boston that the Red Sox had a black ballplayer. FMI, check out http://www.facebook.com/theizzyproject.