Research study focuses on identifying children with autism at higher risk for psychiatric disorders

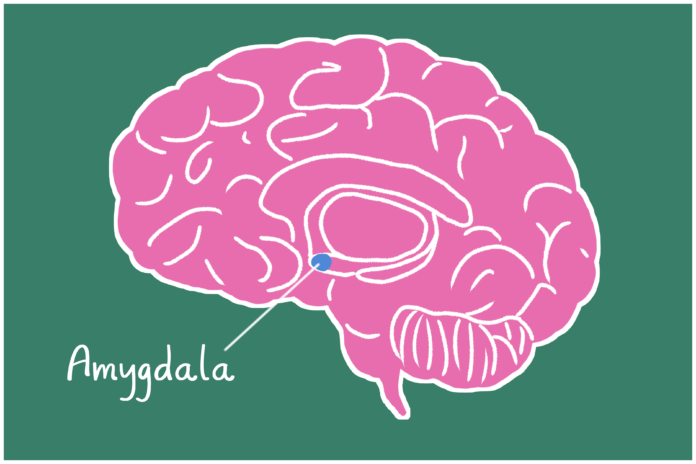

Enlarged amygdalas in young children with autism were linked to high levels of psychopathology, meaning a higher risk of developing a psychiatric disorder in the future, according to recent research conducted at the UC Davis Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (MIND) Institute. The amygdala is the area of the brain commonly associated with emotional responses. Specifically, the research found that young girls were more likely to be categorized in the subgroup at a higher risk of developing a future psychiatric disorder.

“We talk about autism as one thing, but a lot of us also talk about it being very heterogeneous, and what we mean by that is that some people have an intellectual disability, some people don’t, some have verbal skills, some don’t,” said Christine Wu Nordhal, an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the MIND Institute. “The severity of their symptoms can be vastly different as well. The thing that we were focusing on in terms of heterogeneity was this idea of co-occurring psychopathology or co-occurring anxiety, depression, ADHD — disorders that are their own diagnoses but are distinct from autism.”

Although previous studies have seen that there is a higher rate of these co-occurring psychiatric problems in older individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), there has been less focus on researching these rates in younger children. Nordhal first came into this field of research 15 years ago when autism diagnoses were becoming more common. After seeing many families affected by this disorder, along with the lack of understanding of its biological mechanisms, she said she felt it was an important topic to study.

“I felt like it was really important to look at very young ages when kids are being diagnosed if you want to look at the brain basis of autism,” Nordhal said. “Because if you wait until they’re much older, of course, this person has had a lifetime of behavioral interventions or other things that could be, should be, altering their brain in some way to help them. So to look at the most pure sort of neural basis of autism, we wanted to look at right when kids were getting diagnosed.”

Alexa Hechtman, a staff research associate at the UC Davis Medical Center (UCDMC) with the MIND Institute, said that since a majority of autism research is centered around males, it was important to focus on girls due to their underrepresentation. Boys are diagnosed with ASD about four to five times more often than girls, according to Hechtman.

“It takes more time and resources to find girls and bring them into research in order to learn more about them, so, because of that, a lot of research studies are just including males, just for statistical reasons or just the ease of access,” Hechtman said.

In addition, Nordhal thought that a focus on these co-occurring psychopathology traits could help improve the quality of life of these individuals in the future. She clarified that although these psychiatric problems are not diagnosed at age three — the age group that is being focused on in the study — a child who has higher symptoms at this age may be at higher risk for being diagnosed for psychiatric disorders in adolescence.

“This seemed to me like a target where we could actually try to help these kids because there are treatments and interventions for things like anxiety and depression that a parent or family could try outside of their autism therapies,” Nordhal said. “The goal of looking at these co-occurring psychiatric conditions is also because there’s something that we can do about it. If we can identify it in the child, then we can try to help them improve the quality of their life.”

Once the study identified the group of children with high psychopathology within their sample, the researchers decided to look at the underlying neurobiology in order to discover what was causing the larger number of symptoms. The amygdala is a natural target to study due to its common association with autism along with psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression, Nordhal explained. Through MRI scanning, the researchers found that their hypothesis — that patients with higher psychopathology would have enlarged amygdalas — was correct, with almost twice as many girls categorized in this subgroup.

Nordhal explained that although people may generalize behaviors to be within the autism diagnosis, there are subgroups of children with certain behaviors that are different from autism. Informing parents of this and targeting treatments specifically to a child’s behaviors may be helpful. She also hopes that somewhere down the line in this field of research they will be able to track the rate of amygdala development in order to flag children who are at a higher risk of developing future psychiatric problems.

The team will soon begin to investigate the emergence of depression between middle childhood and middle adolescence in individuals with ASD compared to those with typical development, according to Marjorie Solomon, a professor at the MIND Institute.

“We will examine how factors like IQ and social functioning influence who becomes depressed and who does not,” Solomon said. “This will help us to figure out who to treat as we believe psychopathology has an adverse effect on young adult life outcomes.”

Furthermore, the team’s current clinical trial comparing children with ASD and anxiety who are receiving either cognitive behavioral therapy, medication or pill placebo will help clarify which treatments are best for certain individuals.

Hechtman noted the importance of keeping in mind all of the strengths these individuals possess.

“Being able to really focus on what’s special and what you enjoy about that child or individual and just giving them as much support and fostering those areas so that they can have those strengths and grow, versus always focusing on the areas that we need to fix as well — [that is] something that would be helpful,” Hechtman said.

Written by: Michelle Wong — science@theaggie.org