Despite its resemblance to the successful “First Reformed,” Paul Schrader’s newest release lacks cohesion

By JACOB ANDERSON — arts@theaggie.org

If Paul Schrader (director of “First Reformed,” “Hardcore” and almost 20 other films in addition to his writing credits on myth-making films like “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull”) has one defining artistic quality, it is endurance. How else could a man possessed of such rare skill film, script after script, lonely, male, deracinated weirdos struggling against a world that seems to have no place for them? Not that any medium has a lack of artists oozing out the same ideas and themes from the cradle to the deathbed, but with Schrader, this repetition is less meditative and more blunt-force, betraying a willingness to mine his ideas for the entirety of their value. After the unexpected success of 2018’s “First Reformed,” Schrader appears to have doubled down on his recapitulations, condensing his retro stylings into a list of rules which translate quite awkwardly into the modern world portrayed in “The Card Counter.”

Schrader has always vocalized his love for the severe, anti-editorial masters of the mid-20th century like Robert Bresson and Yasujirō Ozu (Legend has it that Schrader once had a licence plate that read “O-Z-U”.) Schrader has now used the ending of Robert Bresson’s “Pickpocket” (1959) in which the protagonist, detained by the authorities but finally self-aware, reconciles with the woman he loves through some kind of police-enforced barrier—if I’m counting on my fingers correctly—three times, composing nearly 10% of his filmography.

“First Reformed,” with its slim budget, appears to have been Schrader leaning into these films as much as he truly wants to: the lack of camera movement and 4:3 aspect ratio summon nostalgia that is clean and careful, perfect for the film’s inner-moving plot. “First Reformed” is brilliant, but it stomps dangerously around the line between being an homage to Ingmar Bergman’s “Winter Light” (1963) and Bresson’s “Diary of a Country Priest” (1951) and using their shooting scripts as a first draft.

Schrader, emboldened, as far as I can tell, by the reverential (no pun) reception of “First Reformed,” has duplicated its approach in “The Card Counter” without reservation, down to the aspect ratio and self-effacing performances. The latter element embodies maybe the most confusing difference between the two: the recreation of Bresson’s “anti-acting” style feels very natural in the rural churchgoers and quivering protagonist of “First Reformed” but synthetic and almost psychopathic in the phone-bearing gamblers of “The Card Counter.” Rather than conjuring an almost dreamlike simplicity, it often feels as if characters are either badly performed or under the influence of hardcore tranquilizers.

The reliance on elements tested in “First Reformed” isn’t surprising or condemnable, but it’s alarming how easily “The Card Counter” has slipped off-course despite their guidance.

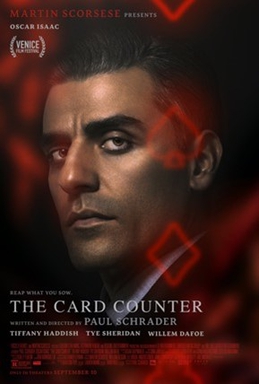

Oscar Isaac’s performance as Willam Tell, a cold, elusive loner, is slow and delicious. He opens up over the course of the film in classic Schrader style, but his internal workings remain obscure enough to keep us absorbed the whole way through. His younger pupil, Cirk, to whom he’s connected by a mutual hatred of a high-ranking military slimeball played by Willem Dafoe (whose rotten, sideways grin is a joy in all of his brief appearances), feels robotic and awkward, as does WIlliam’s love interest, Linda.

But even William himself, despite being the most arresting personality on display, eventually gives the impression of having less going on under the hood than his strange furniture habits and cool demeanor initially suggest. His softness toward Cirk is evident from early on, and his own worries and weaknesses are eventually presented so clearly that there isn’t enough emotional tissue left by the film’s end to connect his various eccentricities, and so he ends up as just a weird guy. The figure isn’t uncompelling, but for a director who mastered this sort of character decades ago, William is undercooked.

The film gravitates around the shadow of the United States’ wars in the Middle East (once again, just like “First Reformed” with climate change) in a way that feels similarly insufficient. We get a good sense of how that cruelty ripples throughout these people, but the thread isn’t enough to transcend that basic sum of its parts. Brief scenes of blaring, visceral torture don’t infect the rest of the film like ravenous parasites; the viewer is inclined to forget they ever happened.

However, beauty is not absent: the patient photography retains impact, and lengthy moments of thought between characters feel rich and purposeful rather than painful. Breakneck cuts and sundry reaction shots are appropriately absent, and we get long looks at empty, sterile casinos. The only truly inappropriate moment (beyond a aneurysm-inducing scene involving Google Maps that intimates a truly boomerish understanding of modern technology) is a scene in which William and Linda go on a date to a sort of Christmas light forest and the camera abruptly and comically soars around on a drone. This and a few comparable but less drastic moments impart a feeling of incongruity that grows as the film approaches its climax; the subtle components of the filmmaking conflict with these dirtier, more modern parts, producing a strange aftertaste that lingers after you’ve finished the film.

It’s more stimulating than most large releases to see daylight recently, but there’s something here that doesn’t come together. If it were just relying on elements from “First Reformed” (Schrader is hardly the first filmmaker to use an idea twice) or harboring some weak characters, it might still reach the heights of Schrader’s more cohesive films, but there seems to be another element at play. Schrader needs to reexamine his approach after this one.

Written by: Jacob Anderson — arts@theaggie.org