Sociocultural issues of the 1920s and today resurface in the Netflix film

By SIERRA JIMENEZ — arts@theaggie.org

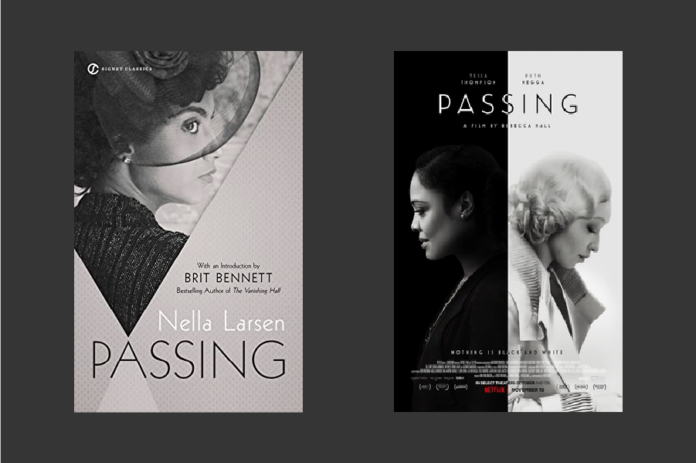

On Nov. 10, 2021, Rebecca Hall’s monochrome film adaptation of Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel “Passing” was released on Netflix. Nominated in the top ten films of 2021 by the African American Film Critics Association, the film stars Tessa Thompson as protagonist Irene “Reenie” Redfield and Golden Globe nominee for Best Supporting Actress, Ruth Negga, as Irene’s literary foil, Clare Kendry.

The title refers to the practice of “racial passing” in which fair skinned African American individuals would “pass” as white to escape racial discrimination in the Jim Crow America of the 1920s. With the political polarity and racial distress currently present in modern America, the film brings up past social issues of race, sexuality and identity still seen today.

Taking pieces of her own experiences as a mixed woman in America and historical events such as the Homer Plessy case of 1892, Larsen utilizes the environment around her to create the characters in her novel. With the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, LGBTQIA+ activism, and other sociocultural movements, the film could not have come out at a better time.

Larsen’s novel is about cultural transformations post World War I, and reveals “changing definitions of concepts like race and gender, and the inextricable relationship between whiteness and blackness,” wrote author Emily Bernard in the introduction of “Passing.” “It is a universal story of the messiness of being human as it is portrayed in the particularly explosive relationship between two black women.”

The novel is structured in three sections: Encounter, Re-Encounter and Finale, much like acts in a theatrical play. According to Bernard, the theatrical structure is meant to represent race as a function of performance and “blackness [as] a matter of perception.” The film is shot in black and white perhaps to visually represent the perception of blackness and whiteness in the story.

The film begins with a white screen and then transitions into a blurry camera view of shoes walking the streets of New York with faint voices echoing in the background. The camera shifts into focus, and the black and white film unfolds from a foggy perspective to crystal clear vision — symbolic of the differing perceptions of race in Larsen’s novel.

Irene Redfield, who could pass as white due to her fair complexion, chooses to associate with her Black heritage and play an active part in the Black community of Harem. Conversely, Clare Kendry, who is also white passing, chooses to pass as white in order to evade prejudice and benefit from the privileges of white society.

Clare represents the New Woman, a notion born in the late nineteenth century of a defiant sexual woman who counters traditional norms. Her mysterious and seductive nature portrayed literarily in Larsen’s novel and visually in the film make her the rebellious character put into question by more conservative characters like Irene.

Irene represents the world of the Black bourgeoisie where race consciousness and racial pride were boisterously talked about in conversation and incorporated in daily life. In the film, Irene coordinates elaborate Black-centered events and is close to white author Hugh Wentworth as a tribute to her elite social class in Harlem.

Clare envies Irene’s involvement with her Black culture and attends these events to compensate for her lack of “Blackness” in the white world in which she lives. She straddles the line between Black and white, which Irene constantly reminds her is a dangerous game.

“Irene is a conservative who is threatened by Clare because she represents a challenge to the sense of order and linear progress endemic to the ‘lifting as we climb’ motto of the black bourgeoisie,” Bernard wrote. “[Clare] is a gambler, playing the high stakes game of racial roulette.”

Their differing identities and their unique struggles to grapple with race are represented by their complex relationship being both beautiful and frustrating. While Irene despises Clare, she also adores her — adores her to a point of sexual romanticization. Through a third person perspective of Irene, Clare serves as “the personification of desire itself” — both a racial and sexual desire.

The film exemplifies the women’s sexual tension through various videographic persepectives and their sensual and slightly embarrassed body language. Jazz music plays over the noir-esque Roaring ‘20’s allure, seductively yet almost uncomfortably placing the viewer between the characters.

Up to the notoriously controversial ending, the relationship between Clare and Irene illustrates, cinematically and literarily, the performance of race and the balancing act of identity in a racially-separated society.

Written by: Sierra Jimenez — arts@theaggie.org