The Manetti Shrem Museum’s new installation challenges dominant power structures through video art

By SIERRA JIMENEZ — arts@theaggie.org

“Why here, why now? Why Davis, why this moment?”

These are questions that Susie Kantor, the curator of the Manetti Shrem exhibition “From Moment to Movement,” asked herself in the summer of 2021 when considering what the museum’s next art installation should highlight. Wanting to curate an exhibition that spoke to the current social and political moment, she chose to focus on protest.

“[This exhibition] shows the relevance of art and the power of art and artists,” she said.

A six piece exhibition with works drawn from the Bay Area-based Kramlich Collection, taking real world events to display moments of protest and resistance around the globe through video art.

“From Moment to Movement: Picturing Protest in the Kramlich Collection” is on display at the Manetti Shrem Museum of Art from Jan. 27 to June 19.

Located on campus for students, faculty and community members alike to enjoy, this exhibition utilizes UC Davis professors and students to help create this beautifully-executed, collaborative installation.

Kantor worked closely from start to finish with the exhibition design team, composed of UC Davis undergraduate design students — Ama Benkuo Bonsu (‘20), Marcus Dubois (‘20), Jen Piccinio (‘21), Alejandra Valladares-Alvarez (‘20), Zoey Ward (‘21), Jovita Lois Wattimena (‘21) and Genevieve C Zanaska (‘21) — supervised by Brett Snyder, an associate professor of design at UC Davis.

These students not only helped design the complicated layout and display of the video-based exhibition, but also designed the opening title piece, catching the attention of viewers from the first step into the exhibit.

The student’s colorful sign which changes from “FROM MOMENT” to “TO MOVEMENT” depending on where the viewer stands, suggests a glimpse of hope that there can be change despite the taxing content.

This exhibition is particularly unique because of its video-based art installations rather than traditional two-dimensional artwork. This sensory experience allows the viewers to fully immerse themselves into the artwork and into these representations of real life moments of resistance.

Through video, a medium so relevant in our everyday lives — especially for students and younger generations — “we hope [the video art] is something that students would connect to” on a different level of familiarity, Kantor said. “Video art allows you to live with [the art] in a different way.”

Although all six pieces in the installation are video works, the artists all use the medium “wildly different[ly],” Kantor said. The different viewer experiences mirror the ways in which “we receive media and how we understand events.”

There is a recommended viewing order of each piece through the installation, starting with Dara Birnbaum’s “Tiananmen Square: Break-In Transmission,” (1988-90). This five-channel video installation with four channels of audio leads the viewer to an active role in experiencing this grandiose piece.

The sound of the Taiwanese students singing “The Wound of History” immerses the viewer as if they were in Tiananmen Square, Beijing in solidarity with the students.

With snippets of real news clips from the student-led protests, the video and sound are overlapped, with some synchronicity from a hidden surveillance camera, picking certain footage to display on a larger monitor, representative of how and what we intake from media.

The exhibition text, written by Kantor, points out, “in this work, Dara Birnbaum zeroes in on the way that the media plays a crucial role in our understanding of the event… the installation mimics the haphazard and creative ways that information was transmitted in the moment: through television footage, audio clips and even fax machines.”

On a much smaller monitor, Mikhael Subotzky’s “CCTV” (2010) displays a single-channel silent video of unedited police footage from Johannesburg, South Africa in 2009 and 2010. Subotzky left the videos unaltered except for deliberately timing the ending so that all suspects look directly into the camera all at once — as if they were all being examined by the viewer.

Stated in the exhibition text, “By turning the subjects’ gazes back on the viewer, Subotzky underscores the way that surveillance practices are used for social control and how these tactics are normalized.”

As you turn the corner of the exhibition, UC Davis professor and established artist, Shiva Ahmadi’s newest animation, “Marooned” (2021), visualizes the impacts of former president Former President Donald Trump’s 2016 Muslim ban through the digitalization of 5,172 rich watercolor paintings.

“This film is an allegory of the labor and determination required to immigrate to a new country and the setbacks so many immigrants face, challenging the myth of the United States as a path to a better life,” as stated in the exhibition text.

Additionally, Ahmadi’s personal correspondence on the exhibition text states, “My practice examines the intersection of religion and politics through storytelling… I was inspired to create Marooned after seeing an image of a young child watching cartoons from behind a table during the bombing of Gaza, a reminder of my own childhood.”

Continuing into the darkest section of the exhibition, the red room of Nalini Malani’s “Unity in Diversity” (2003) lures the audience into the cozy environment to create the physical illusion of being in a middle-class post-independence Indian home.

This single-channel video projection is supported with ornate living-room style components such as black and white framed photographs of Gandhi, furniture and lights. Made as a response to the riots in the province of Gujarat, India in 2002, “Malani points to how the reality of democracy often fails to live up to hard-won principles,” stated in the exhibition’s description.

When you thought the exhibition couldn’t get any darker, the viewer walks blindly into Theaster Gates’ “Dance of Malaga” (2019) — a single-channel larger than life projection with six solid wooden stools fixated in their respective spaces.

This large-scale video art is overwhelming; the content is difficult to watch yet beautifully executed. Meant to illustrate a possible future of what could have been from the small island of Malaga in Maine in the 19th century, Gates utilizes various elements of dance, music, commercials, home videos, historical texts and scenes from the 1959 film “Imitation of Life,” to represent a world void of systemic racism.

“That’s the reason why making art is my political and social platform, and my spiritual and emotional platform…I want my protest to be in the labor of my artistic practice,” stated Gates in the accompanying exhibition text.

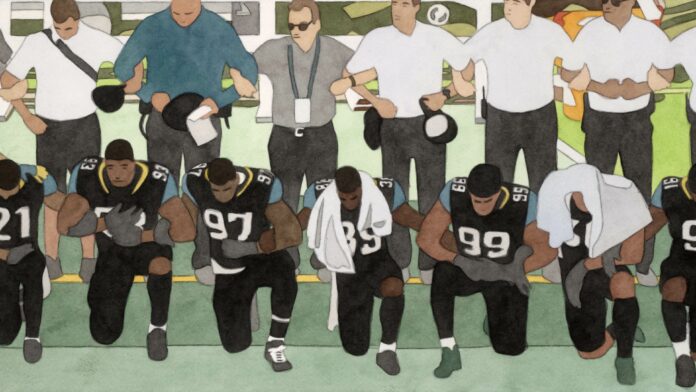

Probably the most recognizable gesture of protest for modern Americans is Kota Ezawa’s “National Anthem” 2018 — a single-channel video composed of digitized water colors that represents the monumental kneel of former San Francisco 49ers quarterback, Colin Kaepernick, during the 2016 NFL season.

With an instrumental version of “The Star Spangled Banner” playing in the background of the muted visuals, Ezawa spotlights the gravity of communal protests without comment.

“As a sports fan, I understood the civic courage that the players displayed in that moment, risking their careers for the benefit of a social cause. It highlighted the connection between patriotism and protest — or that protest can be a form of patriotism,” stated Ezawa in a personal correspondence displayed in the exhibition text.

“From Moment to Movement” is a challenging yet authentic exhibition, drawing attention to the social inequalities, racism and failures of democracy around the globe. The images presented in the film art elicit an emotional response from the viewers.

“I think there are a lot of different ways that exhibitions and artwork can make us feel and make us react,” Kantor said.

Kantor hopes that this exhibition will help bring a glimmer of hope to students and other viewers amidst current socio-political distress.

Working with art has helped shape the way Kantor views and appreciates the world, and she hopes this exhibit will influence viewers in similar ways. With a campus that is heavily research-based, Kantor emphasizes the significance of the arts, and that they are “just as important” in our understanding of the world.

Written by: Sierra Jimenez — arts@theaggie.org