A discussion on how failure contributes to learning and success

By ALEX MOTAWI — almotawi@ucdavis.edu

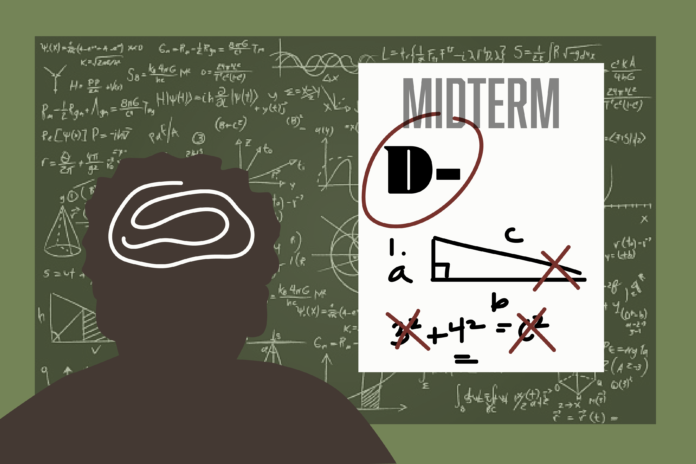

We hear it all the time: “Two steps forward, one step back,” “For every good idea there are thousands of bad ones” and “Nobody succeeds on their first try.” What I want to ask first: Who is “nobody” and how can I emulate them, and second: Are all of these sayings really true? As we all know, failure is a part of life experienced by everybody, but does it inhibit or accelerate learning? Does failure make people give up or try harder? How does failure shape me as a person, and how much of it is healthy? We spend an awful lot of time talking about the thing we try to avoid most, but I believe that failure is better for us than we think — in small amounts.

In my opinion, it feels like we do need to fail a bit in order to push ourselves to do better. If everything I did resulted in a resounding success, I think I would stop trying as hard and put less effort into my next projects. Even if those next projects are still successes, maybe I would stop innovating and trying new things and instead just stick to what’s working versus improving for the future.

We see this in competitive sports all the time. Professional sports call it a “hangover,” referencing the fact that teams often falter the season after winning it all (or getting close). Whether it’s because the athletes got complacent due to constant success or burned out from committing the extra hours it takes to be the best, it’s a real phenomenon. Maybe the real advantage for the future goes to the teams that are hungry to do better after failing in the largest moments of their lives the season before.

However, constant failure definitely doesn’t feel like a recipe for success either. Consistent failure can just feel so degrading that it gets hard to stay committed. It makes people (myself included) feel like they just aren’t cut out for the task in the first place and that their time would be better spent somewhere else.

It makes sense that there is a certain “Goldilocks” zone where we succeed enough that we are inspired to keep working but also fail enough that we are hungry to fix our mistakes and understand that there’s always an open avenue for improvement.

Thankfully, this is a question science is trying to answer. It seems like there really could be a certain wheelhouse where failure is present but not denigrating, and current research points toward following the “Eighty Five Percent Rule for optimal learning.” The rule states that the theoretical best failure rate for learning is a failure rate of 15.87%. If you love doing experiments and deciphering math, there are plenty of proofs in the breakthrough study, but for someone like me who generally trusts in science along with his gut, a failure rate of around 15% just feels right.

Now before you go parroting this “magic number” around to your friends, understand that it’s calibrated more toward things like learning math and not the reason why you are having a hard time finding a date. However, a similar theory does apply to teaching 7- to 8-month-old infants and has been a part of learning strategies without being scientifically known for ages.

With all the nerd stuff out of the way, does that mean getting a B (or anywhere around 85%) in my college class means I’m doing the best learning? And if it’s the best learning, shouldn’t it just be an A instead? Well, our college classes have a lot of variables, so that doesn’t quite check out. You aren’t going to be able to change the minds of your teachers with it, but maybe it can provide solace to all of our struggling GPAs.

If you are acing all of your homework and exams, then it’s simple to say that you might learn better if you had more of a challenge. If you are scoring around the B range on these sorts of assignments, bask in the glory of knowing that you are experiencing optimal learning right now!

In the end, it does seem like failure truly does contribute to success and that it’s been researched a lot more than one might think. The most common proverbs about failure aren’t perfect, but their words do have some wisdom after all.

Written by: Alex Motawi — almotawi@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.