How the printmaker and sculptor explored the unacknowledged contributions of mothers of color

By CORALIE LOON — arts@theaggie.org

Content Warning: This article contains descriptions of violence which some readers may find disturbing.

April 15, 1915: The artist Elizabeth Catlett is born. If her name isn’t familiar to you, you are not alone. For those who do know about her, it is usually for her “intensely political art,” many in the form of lithographs (a type of hand-made print). But alongside her pieces dedicated to moments of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, a different but equally important story emerges.

Elizabeth Catlett, born in Washington D.C., began her career as an artist when she was denied admission to the Carnegie Institute of Technology because she was Black. Instead of backing down, she enrolled at Howard University, a historically Black research university in Washington, D.C., where she studied printmaking, drawing and sculpture.

After getting an MFA in sculpture at the University of Iowa, she spent time in the American South, where she witnessed the regime of Jim Crow-era segregation. For a brief amount of time, she was the chair of Dillard University’s art department in New Orleans. According to the New Orleans Museum of Art, she was devastated at the fact that many of her students were denied access to racially segregated art museums and “defied segregation orders” to take them to see Pablo Picasso’s paintings at the Isaac Delgado Museum. These experiences would greatly influence her political artwork later on.

In 1946, she moved to Mexico City, where she worked at “Taller de Gráfica Popular,” an artist and printmaking collective that “worked to better the social conditions of the working classes, the poor, and the dispossessed.” She became increasingly interested in printmaking, sharing a dedication to accessible and affordable art with others in the collective.

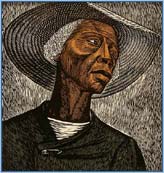

In her series of lithographs titled “The Black Woman,” she honors influential Black women in history, including Phillis Wheatley, Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. “And a Special Fear for My Loved Ones” (1947), instead of a celebration, is a portrait of fear: the sketched body of a Black man on the ground, a noose around his neck.

In addition to the struggles of Black people in America, Catlett was also greatly influenced by Mexican culture through her creation of terra cotta sculptures, many of which show female bodies that resemble the large, muscular bodies in Diego Rivera’s paintings. Her experience with sculpting techniques led to a collection of sculptures that at first appear to diverge from her previous subjects, all titled the same thing: “Mother and Child.”

These sculptures span years and come in numerous styles and shapes, but they all display women of color as mothers, protectors and as hidden symbols of power.

The mother in her 1956 “Mother and Child,” made of a pale and organic terra cotta, is detailed to exhibit “aspects of Black physiognomies” while also remaining anonymous, her body a generalization of motherhood, of the sturdiness and softness of a body whose job it is to keep another life going.

The intimacy of this sculpture, signaled by the mother’s down-turned head and inward posture, is challenged by her 1983 “Mother and Child,” where the mother is standing upright with her head raised. Both her posture and the sharp, geometric lines carved out of wood create a more powerful image.

Her other 1956 “Mother and Child” combines soft terra cotta with a pose that disrupts the one-on-one intimacy of her other mothers. The woman looks out at the viewer and holds the baby facing outward. In this sculpture, she both confronts the viewer and asks them a question: what do you expect of me? Among the stereotyped image of a mother and child, there is room for power, for purpose and for strength.

Through her many sculptures and portraits of women of color in motherly positions, Catlett confronts the inevitability of motherhood and challenges its need to exist separately from politics, social change and the more overt power she depicts in her other pieces. Standing alongside her political lithographs, her portraits of mothers and children acknowledge the joy, the difficulty and the pain of bringing a Black child into an unfair world and, most importantly, of not being acknowledged for your contribution.

In this way, her “Mother and Child” series is a symbolic culmination of elements of her own life: the combination of American and Mexican cultures, the multidimensionality of motherhood and the constant devaluation of the worth of Black women in politics and in personal life. She expertly explores each of these things, while returning through her title to a place of commonality, to the essence of what it means to be a mother and what it means to have a child.

In 1971, Catlett wrote: “Art for me now must develop from a necessity within my people. It must answer a question, or wake somebody up, or give a shove in the right direction–our liberation.” Every woman she paints or sculpts is a part of that liberation.

Elizabeth Catlett continued creating artwork into her 90s until her death in 2012. To this day, her art remains an example of power that knows no boundaries, and that can never remain hidden for long.

Written by: Coralie Loon — arts@theaggie.org