Ideas shouldn’t be monopolized by corporations — cartoon or otherwise

By JOAQUIN WATERS — jwat@ucdavis.edu

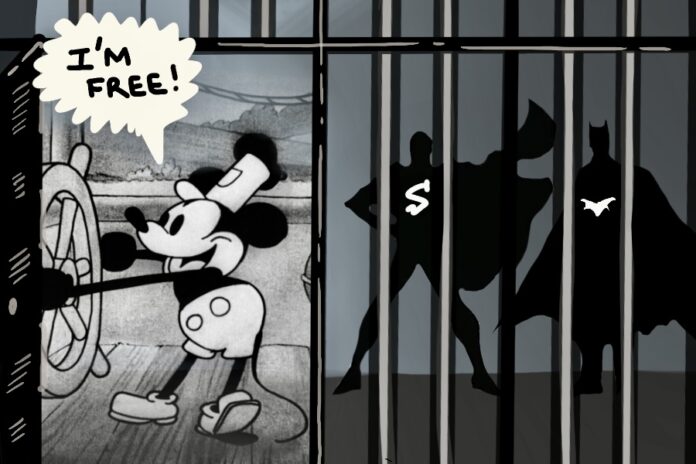

At midnight on Jan. 1, 2024, a quietly momentous thing happened: Mickey Mouse, mascot of the Disney brand and legendary symbol of childhood joy and American consumerism, officially entered the public domain. This means that the original version of the character — the black-and-white incarnation from the 1928 film “Steamboat Willie” — is now free for anyone to use without fear of a cease-and-desist from the Mouse House. An early version of Minnie Mouse is also included.

There are caveats, of course. Since Mickey is also an official Disney trademark, it remains illegal to mislead the public into thinking your iteration was sanctioned or created by Disney. And the most iconic version of Mickey, the one with red shorts and expressive eyes, remains off-limits (though not for long…we’ll get there). Nonetheless, this is incredible news. Anybody can produce and sell a cartoon or a storybook featuring the original Mickey Mouse. Bizarre and creative renditions such as romance novels or horror stories need no longer be relegated to the realm of fanfiction. It’s difficult to fathom, isn’t it? For a character so unanimously associated with corporate intellectual property to suddenly be free for anyone’s legal usage feels impossible. But the day has come. It’s been a long road. Allow me to tell you how we got here, and how in the years to come, this historic moment will be remembered as merely the tip of the iceberg.

The “public domain” is the legal realm that fictional works and characters enter when their copyright expires and the legal hold that the creators and/or distributors of said work dissipates. The expiration of copyright originally came — depending on which was first — 50 years after the creator’s death or 75 years after initial publication. However, in 1998, Congress passed a bill called the Copyright Term Extension Act, after which 20 years were added to each of these expiration dates. Now, copyright expires 70 years after the creator’s death or 95 years after initial publication. Disney was unsurprisingly a major proponent of the bill, leading it to be derisively nicknamed the “Mickey Mouse Protection Act.” But alas, come 2024, they could not delay the release of their beloved Mickey for any longer. And Steamboat Willie is just the beginning; in 2036 their classic 1940 film “Fantasia” enters the public domain, bringing the version of Mickey from “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” — the blueprint for the most iconic versions of the character — with it.

Even earlier (in 2030, to be precise), Donald Duck will join Mickey in the public domain. Duck and Mouse will finally be allowed to profess their undying love for one another and enter into a mutually supportive polyamorous relationship with Minnie — and, more importantly, whoever tells this story can monetize it.

It gets crazier: in 2034, Superman will be free. In just 10 short years, anyone can make a Superman movie — for that matter, Marvel could — so long as they don’t infringe on the DC trademark (in other words, as long as they don’t claim to be associated with DC) and adhere to the character as depicted in the 1938 “Action Comics #1,” in which practically everything we associate with the character is already present (like the planet Krypton and the Clark Kent alter-ego). The following year, Batman joins him. The year after that, so do the Joker, Wonder Woman and Captain America. This turn of events is perhaps even more difficult to fathom; Marvel and DC Comics have built their respective empires by building massive universes out of characters they own. Anything produced outside of their corporate umbrellas is not only illegal, it isn’t considered canon. This concept of canon is central to these characters’ worldwide fanbases, and in only a decade it will start to become irrelevant. Superhero universes won’t be the only ones affected, either. In 2033, the characters from “The Hobbit” will enter the public domain. In 2034, so does James Bond. And the list goes on and on.

Is this a good thing? Certainly not for the corporations these characters belong to. But in this writer’s opinion, it’s tremendous news for art in the long run. Take “The Wizard of Oz”: creative reimaginings like “Wicked” or Disney’s own “Oz the Great and Powerful” would have been impossible to produce had the original novel not entered the public domain in 1956 (pre-Mickey Mouse Act). That’s to the story’s benefit.

Mythology is not a static thing; it is meant to change, to expand, to evolve and take on new forms for new generations. The great irony of Disney’s attempts to extend copyright law is that they built their empire by taking advantage of public domain works like the fairytales of Hans Christen Anderson (“The Little Mermaid”), the Brothers Grimm (“Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”), Lewis Carroll (“Alice in Wonderland”), Middle-Eastern folklore (“Aladdin”) and countless other tales that form the bedrock upon which all the Disney classics are built upon. Practically none of their legendary films would exist without the public domain; the company would have been barred from making them.

Ideas must be free. Perhaps not from inception — artists have a right to profit from their work — but eventually, the day must come. For Mickey Mouse, the day has come. And he’s just the start.

Written by: Joaquin Waters — jwat@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.