Is it better to reign in hell than serve in heaven?

By JOAQUIN WATERS — jwat@ucdavis.edu

When I was a little kid, I went through a phase where I was obsessed with classic Disney movies. I’m sure a solid portion of the people reading this article went through a similar (if not identical) phase. And let’s be honest, folks: the villains are far and away the most memorable part of those films.

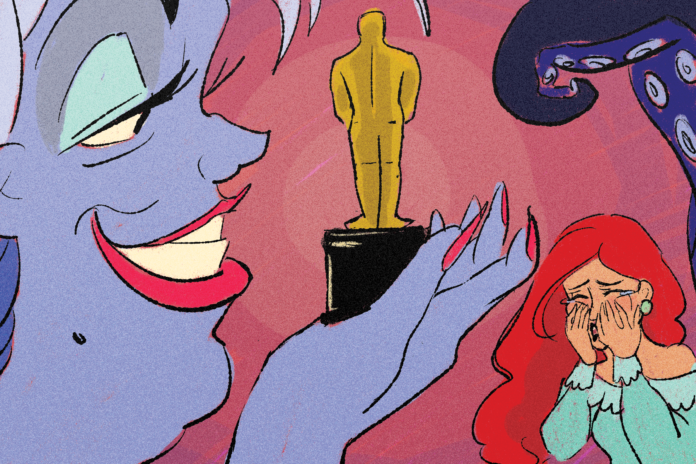

Aladdin is fun, but Jafar is fantastic. We root for Simba, but we count the minutes until Scar is on screen again. Ariel’s quest to find love by losing her voice is…well, more than a little problematic, but when Ursula sings, cavorting around her skeletal lair, it’s easy to forget that.

Disney villains are cultural icons — perhaps even more so than the princesses for which the Mouse House is famous. These films are often our first exposure to the fascinating phenomenon of villain worship, or loving the bad guy.

This impulse — to prefer the villain to the hero — is not unique to Disney films. One needs to only look at the enduring popularity of characters such as Darth Vader, Hannibal Lecter and the Joker to see that the desire to root for the monster is woven into popular storytelling. They aren’t just famous because of their fear-inducing intimidation — audiences actively like these characters.

Every time Darth Vader ignites his lightsaber, or Hannibal Lecter eats someone or the Joker spouts some nasty one-liner, we practically cheer. Sometimes, a villain’s popularity will actually dwindle the less evil they become. Observe the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Loki, a fan-favorite character whose redemption arc culminated in the Disney+ series in which he becomes a straight-up hero — but he was never more popular than when he was blowing up buildings and cackling in “The Avengers.”

There is something monstrously cathartic in seeing the demons of humankind’s collective imagination given voice and form in fiction. And oftentimes, they’re just plain fun. Villains of the type I’ve mentioned here are shameless and flamboyant, possessed of an agency and an urgency that is often lacking in protagonists. Some might argue this is the root of our fascination with the bad guys: nobody likes a passive character, and antagonists, out of necessity, are always active. I think it goes even deeper than that. To look further, we have to go beyond villains to the realm of the anti-hero.

Consider “Paradise Lost.” For centuries, John Milton’s epic retelling of the Book of Genesis has been a subject of controversy concerning its depiction of Satan. Because the poem is told partially from the Devil’s perspective, theologists and literary students alike have debated for generations whether Satan should be considered the “hero” of the poem. If one reads “Paradise Lost” in its entirety, I think it is clear this is not the case. Milton was a devout Christian; the poem is explicitly a cautionary tale that condemns Satan’s rebellion and the ensuing temptation of Eve.

Even still, the debate rages because so many scholars have trouble reconciling that condemnation with the character’s actual presence in the text: Milton’s Satan is complex, charming and even tragic at times — readers like him. Imagine the poem’s most famous line, “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven,” being spoken by your favorite Disney villain, and the dichotomy between the text’s intention and its effect becomes clear.

If “Paradise Lost” is too archaic an example, then consider instead the popularity of anti-hero characters on television. Tony Soprano of “The Sopranos,” Walter White of “Breaking Bad” and the Roy family of “Succession” are characters who take villain worship to the next level. Though they are deliberately written as villainous, even monstrous, they are the protagonists of their respective series.

The audience is meant, at least for the duration of an episode, to side with them. And their massive popularity proves that they do. Like Milton’s Satan, the great TV anti-heroes stand against the texts of the stories they inhabit and choose to reign in hell. And even when the story and audience condemn them for it, there exists within each of us an admiration for the fallen angel.

It has been remarked by many much smarter than me that we hate the most in others the things we fear the most in ourselves. We all have harmful impulses, and we rightly loathe dictators, terrorists and bigots in part because we are all aware of the possibility we each have to become them. We hate the villains of the real world because they give in to hateful impulses.

But in fiction, we delight in hateful characters. As human beings, we are possessed of contradictory desires when it comes to our own self-interest. We want to be rebels, but we also want to be in charge of something. Villains and anti-heroes appeal to us because they represent the part of ourselves that wishes we could do both: be a rebel and a boss. They give us an outlet to celebrate the parts of human nature that are loathed in reality.

Taylor Swift remarked that “it must be exhausting always rooting for the anti-hero,” but I think if centuries of villain-worship have proved anything, it’s that the opposite is true. It isn’t exhausting; it’s exhilarating. Sometimes frighteningly so.

Written by: Joaquin Waters — jwat@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.