Plato’s metaphysics are really weird

By MALCOLM LANGE —- mslange@ucdavis.edu

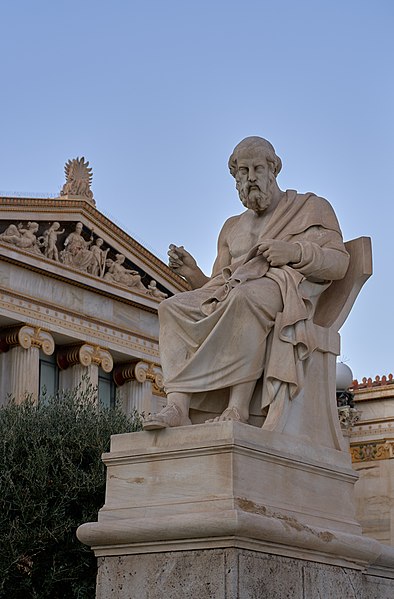

When one hears the term “philosopher,” it is very common to think of the traditional Western or Greek philosophers. Plato — one of the most well-known philosophers — was the student of Socrates and a great thinker in Ancient Greece, writing many philosophical books in the form of Socratic dialogues. But he was also so much more — by the end of this article, you will find that Plato is really just a silly little fella.

A Socratic dialogue is where the main character is Socrates and, surprisingly enough, is in the form of a dialogue, following a first-person perspective of Socrates. Is this weird? Sort of. I mean, if I were to write a philosophical book, I probably wouldn’t make the main character any of my professors (sorry professors), but it is less egotistical than having the main character be himself, I guess.

Socrates, also a predominant philosophical thinker of his time, was sentenced to exile or death for allegedly corrupting the minds of the youth by, essentially, asking them to think critically, especially before going to war. There might be more nuance to it, but as this is not a lecture, and I am not a professor, get off my back. Anyway, Plato, appearing to have not taken the death of his teacher very well — as in later books, such as “The Republic” — blames the idiocracy of democracies and claims that those who sentenced him to his death are simply unknowledgeable of what good truly is.

In Plato’s “The Republic,” he offers many critiques of democracy and gives an interesting claim to what is now called Platonic Metaphysics. His metaphysics are strange, to say the least, but I will try to do it justice for the argument of this article. In my opinion, his metaphysics seem like a lame excuse to explain away Socrates’ death sentence by shifting the blame to the people of Athens.

In the name of simplification, we will first look at Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” In this allegory, we are to imagine that there are prisoners in a dark cave who are only able to look straight ahead; on the wall of this cave exist shadows of objects and people. Behind the prisoners is a fire and people controlling the shadows. To the prisoners, who have been down there their entire life, the shadows are their complete world. Eventually, a prisoner breaks free of his chains and moves through the cave to see the fire — its light burning his eyes as it is brighter than anything he had ever seen before.

This escaped prisoner, let’s call him Bufford (not for any specific reason), realizes that his whole life is essentially wrong; the shadows are, in fact, mere images of what is real — in this case, the objects casting the shadows. Like the fire, the prisoner was blinded by the light of the sun as he reached the exit of the cave, only able to look straight to the ground and view the shadows of objects. After some time, Bufford is able to train himself to look at physical objects and then even, with enough strength, the sun itself.

His whole world is shaken by the revelation of all that exists in the upper world. Bufford feels an obligation to the other prisoners and sets to return to the cave and reveal his findings. However, his eyes are no longer used to the darkness. The prisoners fear this “loss of sight” and deem the upper world dangerous — they would even go as far as killing him or anyone else who would try to remove them from the cave.

This weird allegory symbolizes the different stages of knowledge: those who only see shadows in the cave are at the lowest form of knowledge — “ignorance” — primarily knowing nothing real. Those who make it to the fire know a little more, what is perceived as “opinion” by Plato. Those who can make it out of the cave enter the intelligible world, which is closer to the truth, and have “true opinion.” They might understand mathematics or science but are still only able to look at the shadows of the real truth.

When Bufford looked at the sun, that was the highest form of knowledge: looking upon the “good” and where everything good stems from. Plato claims that most people live their lives stuck at the ignorant stage, with few having the ability to ever make it to full wisdom. I am sure that an astute Plato fanatic would be able to point out mistakes in this summary, but as I have a page limit — and a personal, mental limit — this is the best I can do.

One of the weird claims that Platonic Metaphysics makes is that everything we see, touch and interact with is not real. They are just corrupted versions of the real things, only able to be perceived by looking at the “good.” The intelligible world is the one that holds everything real, while the physical world (down in the cave) holds mere reflections or poor creations of what is real.

Another weird aspect of these metaphysics is that after explaining the cave allegory, he goes on to say that someone who looks at the sun and goes into a dark room will temporarily be blind; the same is true for looking at the “good” and then coming back down to false reality. Their senses might be slightly dulled as they adjust, and it would be unfair to compel them to courts before they have the time to acclimate to the change.

How could you force them to debate on the mere shadows of justice and human evils after having spent so much time in the intelligible world looking upon true justice and goodness? And to try to debate these certain subjects with people who only know the one false way that justice is?

This is clearly a reference to his teacher Socrates and an explanation as to why he lost in court and was sentenced to death or exile. It is hard to tell, at least from “The Republic” alone, if Plato truly believes in his metaphysics or if it is just a way of explaining wisdom. If he truly believed in his writing, it would imply that Plato himself has seen the “good” to some extent. However, especially paired with the allegory of the cave, it appears to be created in the attempts to give a reason for Socrates’ death, claiming that he was still just adjusting to the darkness of the physical world and had to argue with, essentially, idiots who did not know the true meaning of justice.

The latter could be excused enough, with no need for the metaphysics, by claiming that everyone is simply too dull to understand true wisdom and that democracy is at fault for allowing dull people to dictate society. In conclusion, Plato’s metaphysics are strange and, quite frankly, could only have been written by a silly little fella, thus proving that Plato is indeed a silly little fella.

Written by: Malcolm Lange — mslange@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.