The quest for meaning is counterintuitive to art’s true purpose

By JOAQUIN WATERS — jwat@ucdavis.edu

My favorite book I read for my high school English classes was “The Great Gatsby.” I know, I know, basic as heck, right? But hear me out. Most analyses of the book focus on the titular Gatsby, and the ways in which his rise and fall serve as an analogy for the illusory nature of the American Dream. But reading it myself, I was more interested in the POV character Nick, and the ways in which his interactions with the narrative say something about human connection — and the lack thereof — in circles of wealth. There’s a lot to unpack about that character: from how and why he allows his life to become the stage for someone else’s drama to moments of (in my reading, quite obvious) homoeroticism.

So, I was disappointed when, despite my promptings, absolutely none of that was discussed in class. Instead, we simply parroted the same old interpretations about America and the pursuit of a goal. Then we proceeded to jot them all down in our composition notebooks and restated them in the quiz that Friday, and that was the end of it. This is not to downplay these conventional interpretations of the novel; they are widely discussed for a reason. But I believe this unwillingness to engage in less-discussed interpretations is a symptom of a wider “to the test” way of teaching art.

We all know the drill — we’ve been through it a thousand times in a thousand different classes: find the meaning. Write it down. Repeat it on the test. Never think of it again. As if art is an equation, with a single variable to be accounted for that will shed light on everything once we uncover it. I half expect to see this on the whiteboards of half of all art classes: “Politics – Spirituality + x = ‘The Great Gatsby.’ Solve for x, and if your answer is anything but ‘The American Dream,’ you will fail this class.”

As an English major, perhaps it does not behoove me to be saying this. After all, overanalyzing things is kind of our whole deal. But I can’t help but notice a pattern in literature classes (not all, but some) that ascribes, even subconsciously, “right” and “wrong” meanings to all pieces of writing. On some level I understand this; authorial intent is always important to keep in mind. But treating a book or a painting or a film as something to unlock rather than experience makes art so dull. It sucks all of the playfulness out of art, all of the irreverence that is so crucial to making it. Uncovering the One True Meaning of a text tells students, “Okay, that’s it. We solved it. Now put it back on the shelf, and let’s move on to the next thing.” Art is not mechanical like this — it is vitally alive, and like any living thing, it has so many depths and facets that it does not readily show.

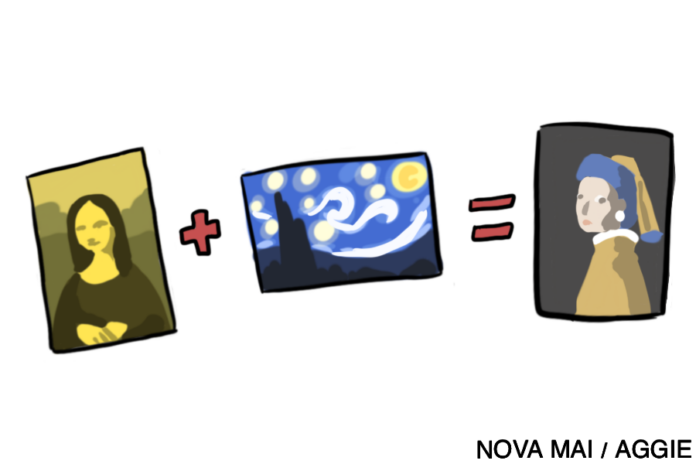

Art is, by its very nature, purposeless. It’s not an equation, it’s not a recipe, it’s a great big mirror through which human beings project their own purpose. A work of art has meaning not in itself, but in what is reflected back in the eyes of the viewer. Some people look at the Mona Lisa and see nothing more than an unflattering portrait. Other people watch a Bugs Bunny cartoon and come away with a thesis about cultural appropriation and homoeroticism in modern America. We should not chastise people for seeing these things; we should not reject them as the “wrong” ways to look at these pieces. We should encourage them, add them to the great big pile of interpretations. Curiosity is crucial not just to art but to academia. Yet too often its early stages are defined by a gatekeeping kind of incuriosity to a fundamentally curious medium.

In no way do I mean to suggest this is rampantly true of every art class I have ever taken. I have had plenty of professors who encourage creativity and do the exact opposite of what I have discussed here. But that just makes the negative examples stand out more. Every time I come across a joyless, mathematical approach to a joyous, messy medium, it just makes me sad. There is no One True Meaning. There are as many ways to read “The Great Gatsby” as there are people on this Earth, and that is what makes it a classic. Only bad books can be so simply reduced.

Written by: Joaquin Waters — jwat@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.