Staff from five different UCs discuss retention, recruitment issues, understaffing, wait times

This article is the second in a three-part series examining issues that counseling psychologists in the UC system are currently facing, including under-market wages, understaffing and high demand leading to systemwide recruitment and retention issues. The final installation will examine how these issues affect UC Davis.

When Rodolfo Victoria, a senior staff psychologist at UC Irvine, first began working for the university as an intern in 2011 and then as a postdoc from 2012-15, every senior staff psychologist was doing about two intakes — initial appointments with students — every week. Now, every senior staff psychologist does an average of four to five intakes a week in order to “get folks in […] within 10 business days.”

But seeing a student within 10 business days is just the goal for an initial appointment and assessment. According to Victoria, the follow-up appointment, to actually give therapy to students, can take up to two to four weeks to schedule. At particularly hectic points in the quarter, a follow-up appointment can take up to six weeks.

In conjunction with what Victoria says is an increase in “the severity or acuity” of student mental health needs on campus, UC Irvine also struggles with recruiting qualified mental health professionals and retaining staff.

“In the last three years, we have been trying desperately to fill vacated spots, and because of the turnover that we’ve been experiencing, essentially over the last three or four years, we’ve only increased our full-time senior staff by one,” Victoria said. “We constantly have searches for a senior staff psychologist — we’ll interview three or four people [and] we offer offers. In the last two or three years, I can list off probably six names of people that didn’t last more than two years. Retention has been a huge issue.”

When asked whether or not UC Irvine was meeting the overall mental health needs of students in a timely and efficient manner, Victoria first said “yes and no.” Later, Victoria qualified his answer. After the initial appointment, he said, “no, we’re not meeting the mental health needs of students. I think we could do more.”

A very similar sentiment was expressed by Diana Davis, the clinical director of Student Health and Counseling Services at UC Davis.

“Sometimes people have to wait for an appointment because we only have so many of those,” Davis said. “We’re very accessible. I think where it gets slowed down is if students want ongoing counseling. We may not be able to see them every week for like four or five weeks and usually […] five sessions is an average amount we can offer students. The appointment, getting it for ongoing counseling, may require a wait.”

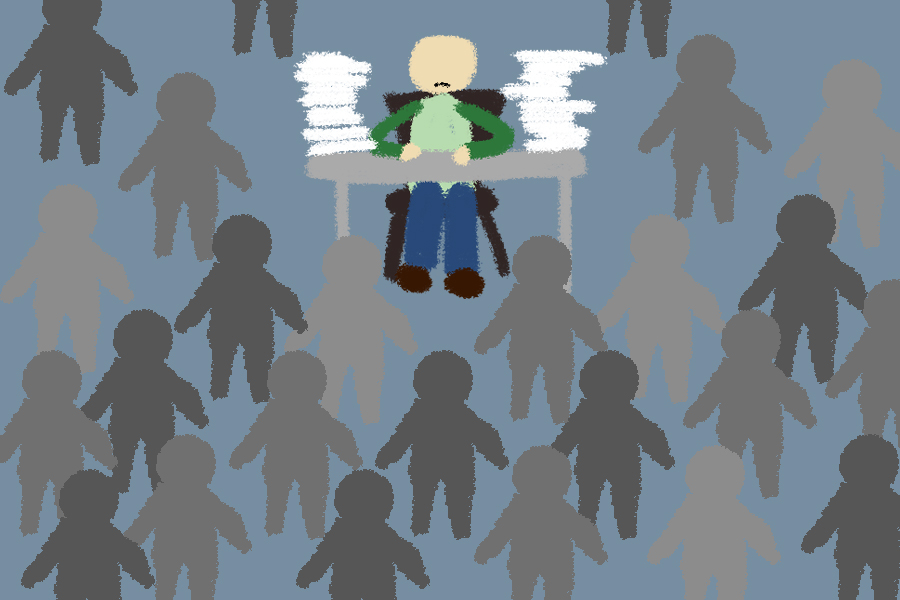

Issues relating to wait times, recruitment and retention, turnover and burnout are apparent at several, if not all, UC campuses. These issues are ongoing, even two years after the UC Office of the President announced serious steps toward promoting and expanding mental health resources at all UC campuses.

In 2016, UCOP announced that an additional $18 million, composed of annual student service fees, would be added to the mental health budget to hire 85 new clinicians UC-wide. According to UC Spokesperson Stephanie Beechem, “as of October 2017, 98 mental health providers have been hired across the UC system.”

“I would expect there’s also a significant number of staff who have left,” said Aron Katz, a psychologist at UC Davis’ SHCS.

The additional hires “will bring UC staffing in line with recommended ratios” of one psychologist per 1,000 to 1,200 students and one psychiatrist per 6,500 students. The staff-to-student ratio UCOP recognizes is a number established by the International Association of Counseling Services, Inc. The IACS states on its website that when a university is not meeting the recommended staff-to-student ratio, there will likely be longer wait times, decreased availability, increased risks for liability and an overall decrease in support for students.

“Imagine the liability that the counseling center and university would have if it was discovered that a student who went on a shooting spree had gone to the counseling center for help only to be put on a wait list,” the IACS website states.

Jamie McDole, the vice president of the University Professional and Technical Employees, which represents counseling psychologists, said she doesn’t know of any UC campus that is currently meeting or close to meeting the IACS ratio.

“There are some campuses that are certainly better staffed than others,” McDole said. “Throughout the campus, the one that is absolutely the worst staffed that I’m aware of is UC Riverside who’s currently at, I believe, six therapists for 22,000 students.”

A source from UC Riverside who wished to remain anonymous stated that the current number of counseling psychologists is five full-time staff members. With a total student body of 23,278, the ratio of psychologists per students is roughly 1:4,655. In the past, UCR has had as few as three full-time psychologists.

“Prior to me working there, UCR lost their entire staff and had to rehire,” the anonymous source said. “I know that […] probably at least over the last three years [they’ve] lost their staff three times. We should be hiring about three times the amount of people we have now.”

According to the source, retention issues are not unique to UC Riverside, but are “especially worse at UCLA and UCR.”

An anonymous counseling psychologist at UCLA spoke about the reality of counseling services at the university.

“I would say UCLA has a reputation in the mental health community in the wider Los Angeles area of being a very challenging place to work at due to the acuity and the large caseloads and the pace of work here,” the source said. “That became rapidly and readily apparent when I began working here. We have a large staff, but we have an enormous student body too, and we also have one of the highest utilization rates of any campus in the country, […] in terms of the percentage of students that seek counseling.”

Due to retention issues at UCLA, the counselor said that when they were first hired, they were “struck” by the number of staff members who would jokingly ask how long they planned to say.

“Like, ‘Are you going to stick around?,’” the counseling psychologist said. “It was very apparent that there was a fear, basically, and sort of a trauma of the number of people that had left. I kept hearing […], ‘We keep losing really good people.’ It’s often like you don’t have any idea why people are leaving either because it’s sort of shrouded in secrecy often due to HR reasons.”

Victoria spoke about a systemwide issue regarding the recruitment and retention of qualified mental health professionals. Just last quarter, Victoria said UC Irvine lost one staff psychologist and one social worker — “we just don’t have enough staff to provide the services that we want.”

“All of this kind of preventative work that we could be doing to prevent the next kind of crisis from occurring, that gets put off and completely put on the side because we can’t give our attention to that,” Victoria said. “We are a place that really values doing preventative outreach work, and that I can tell you has gone down over the years because we just can’t dedicate time and attention to that. I worry that eventually we will simply become just a crisis center — […] that’s an important element of what we do, but it can’t be the only thing that we do. Not only is that not really addressing the mental health needs of students, but it’s not fulfilling. That’s what leads to these burnout and turnover numbers that we’re seeing, because it takes a toll.”

According to the IACS website, after the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting, which left 32 people dead, counseling centers nationwide were “asked to provide training to faculty and staff to help them detect warning signs of students who might be a risk to themselves or others.”

“It would be very difficult to find the time to do this when the counselors are hardly able to keep up with the growing clinical demand,” the IACS website states.

With regard to to the additional $18 million of student fees allocated across the UC system by UCOP specifically meant to bring staff in line with recommended staff-to-student ratios and “increase access to mental health services,” neither the source from UC Riverside, Victoria or a counseling psychologist from UC San Diego who wished to remain anonymous could say definitively how much of the money has come to their respective universities or where it has been allocated.

Another issue prevalent at several UC campuses is the lack of space allocated for mental health resources and professionals. The anonymous counseling psychologist from UCLA discussed their frustration with seeing a multimillion dollar football facility built “less than a hundred yards” from their offices, while the campus says “they, ‘can’t find any more space.’”

“If student mental health is a priority of this campus, as they seem to indicate, it would be important to demonstrate that with actions,” the UCLA counseling psychologist said.

Victoria also said he sees the lack of space allocated to counseling services at UC Irvine as a reflection of how the university chooses to prioritize mental health needs on campus.

“Even if, by some miracle next month we got 10 new staff, where would we put them?” Victoria said. “You can say all the right things about how mental health is a priority to the campus, but unless you show me, it’s just talk.”

The anonymous counseling psychologist from UCSD expressed, almost word-for-word, the same problem.

“Even if we have the money right now and had a great candidate, we wouldn’t have any place to put them,” the UCSD counseling psychologist said.

The IACS website discusses a nationwide trend regarding the increase in the severity of mental health issues in recent years.

“Of the 367 universities and colleges that filled out the National Survey of Counseling Center Directors (2013), 95% reported that the number of students with severe psychological problems has increased in recent years,” the website states. “As the severity increases, so does the time that’s required by the mental health professional to adequately manage the case. Thus, the ratio of counselors to students should actually decrease as severity of issues increase.”

The UCSD counseling psychologist, alongside the aforementioned sentiments from Victoria and the counseling psychologist from UCLA, discussed an overall increase of the acuity in the problems seen on campus.

“My biggest concern is wanting to not just have the quantity of staff but the quality of staff,” the UCSD counseling psychologist said. “Our staff is really hard-working. The stuff that we’re dealing with is not what some of the administrators would make it sound like, like we’re just dealing with people with relationship problems or someone’s having trouble in their classes. We’re dealing with really intense, acute issues — people who are seriously contemplating suicide, people who are going through their first mental or psychotic break. It’s just a ton of stress that we have in our job, and there’s this pressure that we need to be the ones preventing anything from happening, like preventing someone from acting out in a suicidal manner or a homicidal manner. I know that’s something that weighs heavily on our staff. With limited resources, that just adds to […] the pressure and stress and frustration, […and] it’s a reality of our experience as a psychologist on campus.”

Written by: Hannah Holzer — campus@theaggie.org