As our world grows increasingly connected through technology, the opportunity to interact with others from different cultural, political and religious backgrounds is also increasing. Social media allows users to communicate with individuals across the globe in mere seconds, promoting civilized sharing of ideas across cultures and, consequently, building a more tolerant global environment with less conflict.

As our world grows increasingly connected through technology, the opportunity to interact with others from different cultural, political and religious backgrounds is also increasing. Social media allows users to communicate with individuals across the globe in mere seconds, promoting civilized sharing of ideas across cultures and, consequently, building a more tolerant global environment with less conflict.

But the sustained cycles of war, bigotry and injustice within nations and their residents prove otherwise, frequently defining the social and political atmospheres both between and within countries. As accentuated by the recent presidential election, the failure to connect with different cultures is painfully evident within our country — a nation ostensibly founded on tolerance and freedom.

This past year in politics has dishearteningly shown that instead of learning about and embracing the unique backgrounds of other Americans, many citizens automatically resort to fear of cultural differences and foreign communities. An increasing reluctance to be sensitive to the hardships of other cultures reflects a dearth of empathy deemed acceptable by many American residents and leaders.

And simmering cultural intolerance isn’t just a phenomenon of the presidential election. Recent studies have provided empirical evidence of decreasing levels of empathy among Americans over the past few decades, often pointing to Millennials’ self-centered behaviors that earned them — well, us — the title “Generation Me.”

College students today, despite being one of the most liberal and open-minded populations in American society, have displayed lower levels of empathy in comparison to older generations.

A study published in 2010 by the Association for Psychological Science by the University of Michigan noted that college students’ empathy has dropped by a staggering 40 percent since 2000, while the National Institutes of Health reported that 58 percent of college students in 2009 placed higher on the narcissism scale than those in 1982.

Yet our generation has theoretically enjoyed more access to humanizing pieces of information than any other age group in history. Why haven’t reports on nations in crisis like Syria inspired compassion within us? Why has technology failed to repair our nation’s “empathy deficit” that President Obama warned about a decade ago?

Despite the staggering amount of information available from our pockets, there isn’t a huge incentive for users to inform themselves about unfamiliar concepts or cultures through technology like the Internet. People often structure their social media experiences to reflect their already-established interests — following Twitter accounts, reading news sources and subscribing to subreddits that merely reiterate and reaffirm their beliefs.

Perhaps most troubling is the magnitude of users unaware of their ideological insulation. Facebook admitted to using algorithms for its news feed that muzzle opinions conflicting with users’ views. Social scientists Walter Quattrociocci, Antonia Scala and Cass R. Sunstein further published a draft paper offering quantitative proof for the existence of echo chambers on social media sites, particularly Facebook.

This becomes even more worrisome when you consider that two-thirds of American Facebook users — a little under half the US population — utilize Facebook as a primary news source.

Even when confronted with new or opposing ideas, technology doesn’t require individuals to participate in actual civilized discourse. One glance at the hellish cesspool of Youtube’s comment section shows that trashing others’ ideas often comes more easily than engaging in respectful conversations.

But the world is more diverse than our individual beliefs. Although it’s perfectly valid to use technology to refine one’s argument, the inability to honor or even encounter contrary ideas is detrimental to growing empathy, which requires putting oneself in the mindset of another — a process key to understanding anyone with a radically different background.

Hearing others’ stories triggers our brains’ mirror neurons, which are central to strengthening empathy. It’s no surprise, then, that researchers at The New School found that reading works of literary fiction — which frequently offer intense glimpses into the psyches of central characters — enhances our capacity for empathy.

Literature has repeatedly been at the forefront of social change because of its ability to incite widespread empathy. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin depicted slaves as human beings — showing Southerners, many for the first time, that their shackled workers weren’t just property. Stowe additionally shocked Northerners who were indifferent towards slavery by displaying the cruel treatment of slaves by their owners. Uncle Tom’s Cabin became the second best-selling book in the United States, helping to spur the 1850s abolitionist movement. By humanizing slaves through storytelling, Stowe transformed not just a few apathetic hearts, but an entire nation.

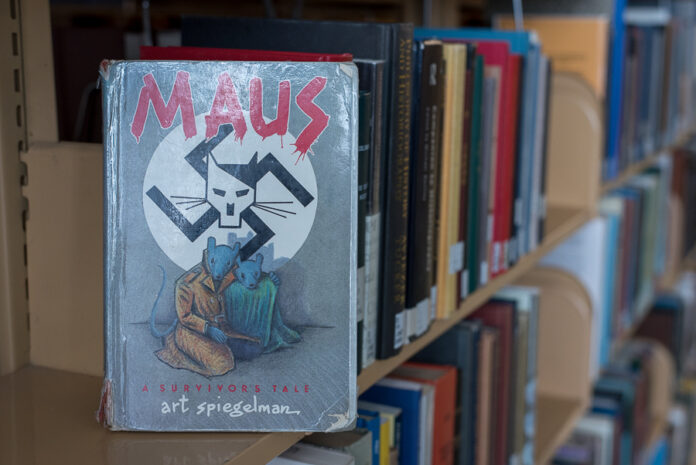

Another example of the influence of storytelling on empathy comes from Art Spiegelman’s Maus, the only graphic novel to have won a Pulitzer Prize. Maus follows the extensive conversations between Art Spiegelman and his father, Vladek Spiegelman, a Holocaust survivor.

I was startled by my deeply emotional response to Maus. I had learned about the grisly horrors of the Holocaust in school. I had seen The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas and studied The Diary of Anne Frank. A year and a half ago I read Man’s Search for Meaning, a harrowing memoir recounting Viktor Frankl’s time in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Since I had accumulated knowledge about the Holocaust throughout my life, I didn’t expect to walk away from Maus feeling fundamentally changed.

But understanding doesn’t just entail knowledge — true empathy requires the emotional experience of imagining one’s self in another’s position. As Vladek’s suffering — which included witnessing the capture of his family and friends and the extermination of those around him — unfolded before my eyes in Spiegelman’s illustrations, I couldn’t help but put myself in his shoes.

How would I say goodbye to my parents, knowing that they could be taken directly to the gas chambers in Auschwitz? How would I reconcile the insurmountable sadness of knowing that my brothers were to be gunned down and thrown into a mass grave?

Sobering, excruciating questions like these that have made me think about Maus almost every day since I finished it.

But beyond Vladek’s story, I acquired the perspective of a Holocaust survivor’s child. Part of Maus’ effectiveness stems from Spiegelman’s ability to skillfully juggle multiple mindsets. He thoroughly examines not only the life of a Holocaust survivor, both during and after the war, but also the heartbreaking guilt many second-generation Jews experience.

I never considered the reverberating consequences of the Holocaust, besides the loss of family and friends, on successive Jewish generations before reading Maus. Art Spiegelman admits, “I feel so inadequate trying to reconstruct a reality that was worse than my darkest dreams. And trying to do it as a comic strip!” The sheer weight of being a survivor’s son, unable to comprehend the past trials of his parents, never crossed my mind.

Most significantly, I experienced these emotional revelations in response to a tragedy that’s already considered one of the most horrific in history. I became more empathetic towards a group for whom I already possessed great compassion.

Ultimately, knowing that six million Jews died as a result of Nazi persecution wasn’t enough. No statistic can capture the emotional and mental impact of something as devastating as the Holocaust. Even if they’re relaying crucial information — like the inconceivable death toll of genocide — pure statistics dehumanize and erase the personal stories of their subjects. It’s easy to use statistics to strip away the humanity of large groups of people.

One of the most recent and obvious examples of this tactic can be found in Donald Trump’s campaign, which has thrived on fearing “the other” — whether that insinuates Syrian refugees, Mexican immigrants, women or simply anybody speaking out against him.

He depicts Muslims as monsters by (falsely) claiming that “thousands and thousands” of Muslims celebrated in New Jersey as the World Trade Center collapsed. He (falsely) declared that the majority of Mexican immigrants are criminals, drug dealers and rapists.

His son, Donald Trump Jr., likened Syrian and other refugees — persecuted individuals with heartrending stories — to Skittles to make an egregiously false statement about potential terrorists entering the US (when, according to the State Department, fewer than 20 out of 785,000 refugees have been arrested or removed for terrorist concerns).

Dehumanizing methods like the ones employed by Trump discourage cultural acceptance and often lead to unprovoked violence, like the attack on a homeless Mexican man by two Boston brothers.

They claimed that “Trump was right — all these illegals need to be deported.” The attackers exemplify the consequences of dehumanization and ignoring empathy: in their eyes, Mexicans aren’t human — they’re “illegals” who deserve punishment.

When presented as facts, Trump’s unfounded quips and statistics silence the stories of thousands of people. And without a conversation, there’s little hope for empathy.

Whether Hillary Clinton or Trump win the election on Nov. 8, the effects of Trump’s campaign will continue to haunt the nation. His offensive remarks have damaged countless communities and exposed the prejudices in our culture. But rather than simply bemoaning the events of this election, I still believe in the ability to change hearts through storytelling.

Perhaps we thought our nation was better than what we’ve revealed during this past year and a half. But now that we know these prejudices exist, we can start making changes in the right direction.

Rather than slinking away to our separate political corners on Nov. 9, we need to engage in thoughtful conversations about the future of our country — with gentleness, compassion and a recognition that those across the political aisle are also humans.

Social media can spread stories and increase empathy, but only when it’s used to its full potential. While the echo chambers of most social media sites shield individuals from contrary opinions, polarize ideologies and prevent progress, users don’t have to remain unacquainted with the world’s extensive spectrum of beliefs.

Social media must work to bridge the divide between political parties, religions, races, genders and cultures. By providing a platform to communicate with people from a multitude of backgrounds, technology has granted us the ability to create an environment more harmonious and empathetic than ever before.

For the safety of our nation and fellow human beings, we can’t continue living in our own ideological bubbles.

Written by: Taryn DeOilers — tldeoilers@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.