Pour yourself a cup of ambition and let’s get to it

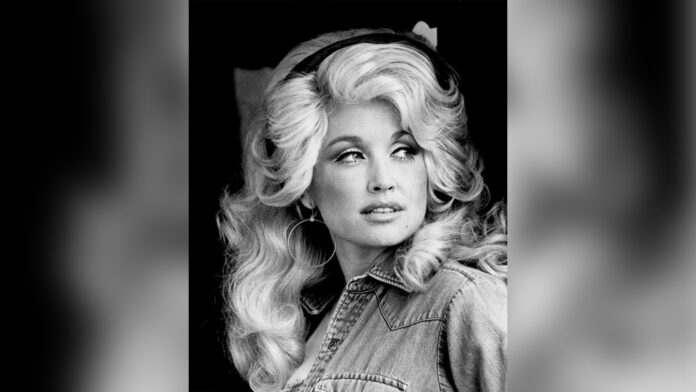

I’ll start with what the reader should take away from this article: Dolly Parton is iconic. Dolly Parton is the queen of country music. And I say this with the confidence of a relatively new fan — I only really began to dive into her music and familiarize myself with her canon beyond “Jolene” and “9 to 5” during Fall Quarter of 2019. Her songs now frequently appear on my quarterly-made playlists, and they seem to play on repeat. Her songs instantly perk my mood, and even her heart-wrenching love songs have the ability to make a sad situation feel, at the very least, warm.

The key to Dolly is the passion evident in each of her songs. There is power rooted in her vocals, which is able to expand on the simplicity of concepts characteristic of country music and instill the emotions of pure joy, deep heartbreak and nostalgia for simple moments.

Dolly deserves modern recognition for her pioneering as a female country singer and her continued success since the 1960s. Indeed, my love for Dolly partially stems from her often unacknowledged feminist content. It’s essential to note that Dolly does not consider herself a feminist, as she admitted in the WNYC podcast “Dolly Parton’s America.” Yet, even if she doesn’t consider her music to hold such a sentiment, that’s not to say that one could not still find such appeal.

She is a force to be reckoned with within a music genre dominated by machismo; she demands respect in a variety of ways. She calls out mistreatment from men, and she calls out inequality. She celebrates her womanhood. While there are plenty of other female country musicians with much more explicit calls for gender equity — like Loretta Lynn’s “The Pill” — the popularity of a female singer who can embed discreet notions of female power is worthy of praise.

There is something to be said for an artist who is able to appeal to an audience intertwined in mid-20th Century gender ideals while presenting them a new perspective to consider. It’s important to recognize and contextualize her music within both the social norms in which she was singing as well as her own musical intentions. Ultimately, Dolly is not a freedom fighter. I would not equate her to the ranks of figures like Gloria Steinem, for example. Nonetheless, she should be praised for her effort to raise a new point of view and acknowledged and respected for the contributions that hold a feminist twang: love for others and reflection.

I can understand the intimidation of attempting to familiarize oneself with such a long-standing artist with dozens of albums. And I must admit, I have only begun to scratch the surface of her discography. My taste in country music gravitates toward folk, a consequence of my old-fashioned cowboy familial roots. I was taught to appreciate musicians like Marty Robbins, Johnny Cash and Hank Williams. Therefore, I have gravitated less toward Dolly’s modern tracks and more toward her earlier ones. Two of her albums, “Hello, I’m Dolly” and “Jolene,” serve as both a foundational introduction to Dolly Parton as well as my favorite albums of her to date.

Let’s start with “Hello, I’m Dolly,” her 1967 pilot album. The album is goofy and endearing. In “I Don’t Want to Throw Rice,” she describes wanting to throw rocks instead of rice on the wedding day of the woman who stole her man. In “Something Fishy,” she sings of concern that her boyfriend is cheating on her during his so-called fishing trips. I can’t help but giggle at some of the absurdity of a young Dolly’s expressions of fear and jealousy. A similar sense of adolencence is illustrated in the album’s opening track “Dumb Blonde.” She rails at an ex-lover who calls her a dumb blonde upon confronting his infidelity. She responds with the ultimate comeback: “And you know if there’s one thing this blonde has learned, blondes have more fun.” Go get ‘em, Dolly.

While still a little silly, the undeniably catchy track sets an early precedent for the type of confidence and individuality Dolly exudes in her music. Yes, much of Dolly’s image of fame has centered on her appearance — an oversexualization created for and by the male gaze. What differentiates Dolly, and what makes me respect her as an artist, is the control she embraces from the attention she receives. It’s her blonde hair, it’s her body. She sources a sense of independence and outspokenness from her physique. She even claims this power more directly in the ballad “I Wasted My Tears.” Indeed, in her hypnotic vocals of the second verse, she claims “I wasted my time when I spent it with you.” The beauty of this album stems from knowing the maturity that is soon to come in her budding career.

By 1974’s “Jolene,” Dolly had grown up: her music was even more raw, her song writing more complex. Musically, it’s more somber. The innocence of her first album had departed, replaced with clear evidence of significant heartbreak. Of course, arguably her most popular song, “Jolene,” is a perfect example of such: expressing fear her husband will leave her for a woman with “ivory skin and eyes of emerald green.” Yet the album reaches deeper in songs like “When Someone Wants To Leave,” “Living on Memories of You” and “Lonely Comin’ Down.”

One of her best songs is also in this album: “I Will Always Love You.” In fact, Whitney Houston’s famous rendition was a cover of this Parton original. In each song, Dolly describes the dramatically painful moments of relationships ending with digestible simplicity. The pain of an unreciprocated love, the physical pain one experiences during heartbreak, nostalgia for when times were good. She doesn’t overcomplicate her emotions or describe them as lofty. Dolly is so appealing because she doesn’t try to be more than what she is, she doesn’t seem to take her song writing so seriously to the point where it misses the connection and intimacy she hopes to establish with her listener. Her impressive vocals and accurate lyrics do the work.

There is a sense of nostalgia in the album as well. In “River of Happiness” and “Early Morning Breeze,” she uses imagery of serene moments in nature as points of reflection. She views these experiences of scenic isolation as meditative — finding the beauty that is rooted in heartbreak, the deep connection one must find within themselves as they experience the increasing complexity of love that comes with age. I find this album to be a coming-of-age album for the artist, displaying her own maturation and guiding us through ours. Dolly doesn’t let us forget that she too shares the same emotions we feel.

I urge you to take the dive into Dolly Parton. She has been the artist who taught me the value of learning to love dancing by yourself while you get ready in the morning.

Written by: Caroline Rutten — arts@theaggie.org