Skin forms differently at certain body sites, which are predisposed to specific dermatologic diseases

By BRANDON NGUYEN — science@theaggie.org

The skin is an organ that functions beyond cosmetic fashion and biological protection. Its composition and layers differ in different areas of the body for specialized functions, which can in turn predispose individuals to location-specific diseases. According to the American Academy of Dermatology Association, about 84.5 million Americans are affected by skin diseases due to aging, trauma and environmental causes.

Two recent studies conducted by UC Davis Health researchers uncovered secrets of the skin that revealed both how and why the organ forms uniquely throughout the body. Dr. Emanual Maverakis, a professor of dermatology and molecular medical microbiology at UC Davis Health and senior author on both studies, provided insight into the initial inspiration to research the skin.

“This will be the first of many studies, and I’m very interested in knowing how the different areas of the skin are designed differently because, if you think about your face, [the skin] has to be thin and flexible for you to be able to communicate visually with people — make a facial expression, smile, frown, get upset and so forth,” Maverakis said. “But on your palms and soles, it has to be very thick and rigid to overcome frictional forces of walking.”

Through research and clinical work, Maverakis noted that dermatologists like himself have noticed how some diseases only occur on certain body sites.

“For me, that means that not only is the skin structurally different, but it probably has a different immune system,” Maverakis said. “That’s where our future research is going to focus more on: characterizing how the skin differs immunologically at each body site.”

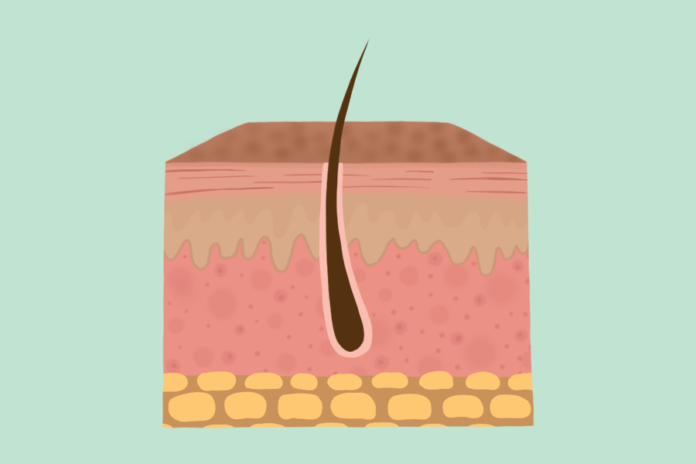

According to Maverakis, his first study focused on how the skin’s immune system is different on different parts of the body — specifically on just the top layer of the skin, the epidermis. While the superficial layers protect the body from pathogens, they must also communicate with the deeper layers to recruit immune cells in cases of infection.

In addition, the epidermis has a fatty lipid matrix composed of fatty acids, cholesterol and ceramides that help shape the structure of different areas of the skin depending on what genes are expressed. While these lipids act like glue for the skin, cells called keratinocytes serve as the bricks to stabilize the skin composition.

Using single-cell sequencing, Maverakis and his team characterized how these lipids and keratinocytes varied depending on their location on the body, matching gene expression with compositional differences in the skin. For Dr. Stephanie Le, a dermatologist at UC Davis Health and the lead author of the first study, these findings were major steps toward more precise dermatological care.

“A lot of our medications, like special topical medications, are made ‘one-size-fits-all,’ [but] the rest of our body skin on our body sites are different,” Le said. “So I think that really led us to wonder how this can be tailored specifically to patients. Precision medicine is definitely something all of medicine is moving toward, and I think that this is just one step toward it, opening up potential for noninvasive testing that can be done by primary care providers and easily analyzed for a quicker and more accurate diagnosis.”

Dr. Alexander Merleev, a postdoctoral researcher on Maverakis’ team and the lead author of the second study, highlighted how understanding lipid alterations could also aid in dermatologic diagnoses.

“Lipids stuck to a piece of tape [that was previously] applied to the skin were sufficient to diagnose a patient with a particular skin disease after sending the sample to a lab,” Merleev said. “These discoveries will lead to [noninvasive] tests for common dermatologic disease.”

Echoing Le’s sentiments, Maverakis also emphasized how medications for the skin will change based on the studies’ discoveries and the trend toward precision medicine in general.

“Our goal is always to make medicine more specific,” Maverakis said. “For example, now we know how the lipids differ across the body. If you’re going to use a moisturizer, you could design it to repair the lipid defects at that particular body surface. So what you put on your foot — if you have dry heels, let’s say — should be totally different than the one you apply to your face because the lipids are very different from your foot and in your face.”

Written by: Brandon Nguyen — science@theaggie.org