Mixing DNA genotypes at coral nurseries can help prevent disease outbreak and spread

By LILLY ACKERMAN — science@theaggie.org

A recent study from the UC Davis Department of Evolution and Ecology has found that placing corals of different genotypes together at a nursery can improve the population’s overall resistance to disease.

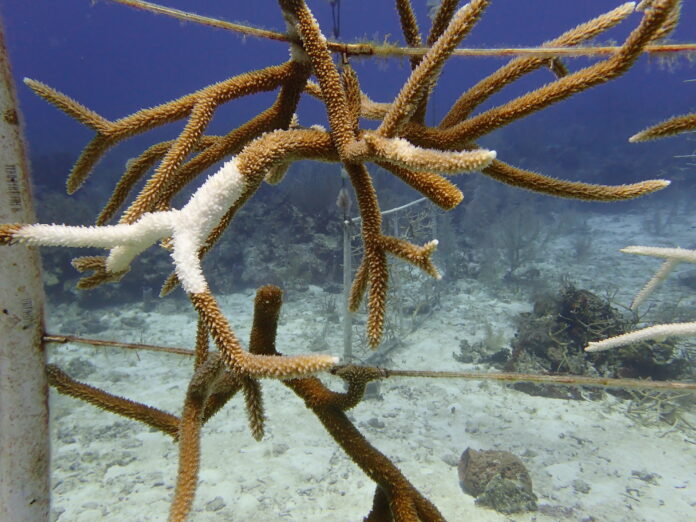

The study researched the prevalence of white band disease, which has been affecting corals in the Caribbean for several decades, in both resistant and susceptible corals at a nursery offshore of the Central Caribbean Marine Institute in the Cayman Islands. It found that disease-resistant corals can prevent the spread of disease to susceptible corals they are attached to.

The staghorn corals (Acropora cervicornis) at this nursery are crucial reef-building corals in the Caribbean, but their populations have seen steep declines due to disease outbreaks since the 1970s, according to Dr. Anya Brown, an assistant professor in the Department of Evolution and Ecology at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory and lead author of the study.

“[White band disease] is still present today and affecting the acroporid corals in the Caribbean, and often, the acroporid corals are the ones that are used in reef restoration,” Brown said.

Nurseries are a crucial part of reef restoration, as they grow corals of a variety of genotypes, but they are subject to disease outbreaks just as wild corals are, according to the study.

The authors compared disease prevalence on a variety of plastic frames that the nursery used to hold growing corals; some held coral fragments of mixed genotypes, while others contained corals of only one genotype. The study found that frames with mixed genotypes experienced less infection with white band disease.

“Some of the corals that are vulnerable to disease can be ‘rescued’ by resistant genotypes, likely because resistant genotypes prevent the transmission of the disease between fragments,” the study reads. “In fact, when the resistant genotype was present on a frame, disease prevalence […] tended to be lower than on other mixed genotype frames when the resistant genotype was absent.”

This finding is critical so that nurseries can encourage the maintenance of both resistant and susceptible corals in the population and manage disease spread among them.

“Disease is one of the many different factors that are impacting corals negatively right now, so [a coral] that might be susceptible to disease may have other traits that are helpful for other types of stressors,” Brown said. “Keeping the genes of both susceptible and resistant corals in the population or on the reef will be important for future stress experiences.”

According to Dr. Brown, the study also provides insight into effective nursery design and the mechanisms of disease spread, both of which need to be taken into account when raising corals for reef restoration.

“Thinking about how you arrange the corals intentionally can influence their survival or their ability to be diseased or not diseased,” Brown said. “This is giving us also just a better idea of…the processes that influence disease spread on reefs; what might limit disease spread and what might not limit disease spread.”

In the effort to solve the coral conservation puzzle, this study is a step in the right direction.

“I think there’s a lot we don’t know about coral diseases and their spread on reefs, and so this is a start for our understanding of these population-level processes,” Brown said. “It’s nice that not everything is doom and gloom.”

Written by: Lilly Ackerman — science@theaggie.org