The lecture defined fascism in a way that echoes present-day American politics while warning the consequences of inaction

BY JULIE HUANG — arts@theaggie.org

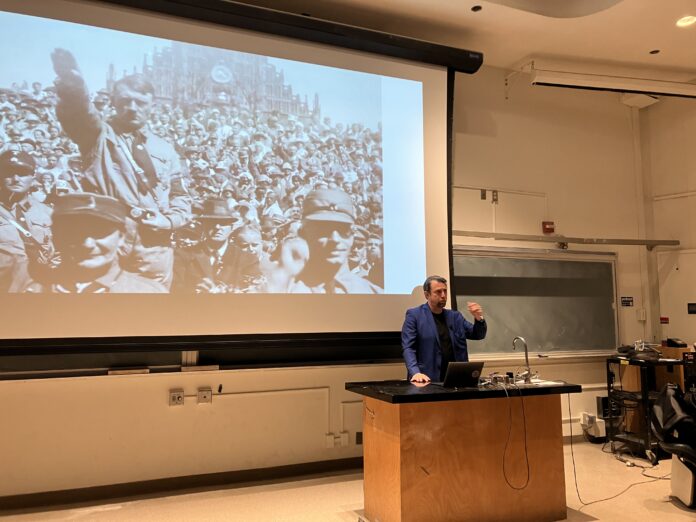

On Feb. 18, the UC Davis Department of History held a lecture given by Professor Adam Zientek on the “Machtergreifung,” referring to Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1930s Germany.

Over the course of an hour and 20 minutes, Zientek sought to detail the process by which Hitler established a fascist dictatorship within a highly literate and cultured republic, revealing how quickly fascism takes root even in societies that are committed to democracy.

“I’ll give the moral of the story away at the beginning,” Zientek said. “Hitler only came to power because he had lost.”

After Germany’s tremendous losses in World War I, many Germans turned to the “stab-in-the-back” myth as a soothing explanation for their defeat. Many small, right-wing political parties, known as “patriot parties,” promoted the idea that Germany’s loss was caused by traitorous internal enemies, which included socialists, communists and Jewish people, who had betrayed the invincible German army when they sued for peace in 1918. This narrative, although not grounded in reality, resonated strongly with middle-class German veterans, one of whom was Hitler.

Only after Germany’s defeat in World War I did Hitler resolve to become a politician, becoming drawn to the German Workers’ Party, a small, far-right party that subscribed to the stab-in-the-back myth.

“They shared a group identity as honorable and brave patriots who had their glory taken from them by the left, the French and the Jews, stewing in resentment and shame,” Zientek said. “They were exactly Hitler’s kind of people.”

Following his entry into the German Workers’ Party, Hitler spent years honing his oratorical skills in the beer hall where the group met.

“Up to 6,000 people a night would sit transfixed and listen to him as he raved that only he could protect Germany from Jews and save Germany from international bankers,” Zientek said. “Hitler’s language in these speeches was ugly, brutal, coarse and omitting facts — a program that you’d think would be unpopular, but you’d be wrong.”

In 1923, Hitler attempted a coup d’etat and was convicted of treason. Yet being prosecuted made him more popular than ever, and attempts to hold him accountable only increased his influence and his belief that he was the victim of political persecution.

“Hitler’s coup taught him the lesson that overthrowing a democratic state was not done through violence,” Zientek said. “Through legal means, he could pervert and then take over the parliamentary institutions of government to establish a one-party state.”

Millions of Germans who had never heard of him read about his trial in the newspaper, giving him a platform to promote his ideas.

“Nazism became about winning hearts and minds, blackening the former and emptying the latter,” Zientek said. “Hitler’s goal was to win enough votes to destroy the opposition once and for all.”

Yet Hitler’s brand of far-right extremism was unpopular in 1920s Germany due to growing economic prosperity and cultural optimism. Germany experienced a series of diplomatic victories in the 1920s, was welcomed back into the League of Nations and largely reintegrated into the European economy by 1929.

Only after the economic crash of 1929 did interest in the Nazis’ radical solutions begin to grow.

“This was devastating for the living standards of ordinary Germans, and it seemed to prove that democracy, liberalism and capitalism had failed catastrophically,” Zientek said. “These things that had promised prosperity and peace produced a world in shambles. The German people looked for alternatives, and the Nazis had them.”

Before continuing his discussion of Hitler’s rise to power, Zientek stopped to explain what he meant by fascism, citing historian Robert Paxton’s definition of the term.

“Fascism may be defined as a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood, and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in an uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints the goal of internal cleansing and external expansion,” the definition reads.

Zientek went on to list other characteristics of fascist ideology, which include the superiority of one’s own group above others and dread of that group’s decline under liberalism, as well as class conflict and alien influence, which supposedly justify domination of other groups without any legal or moral constraints.

“This is as good a definition as you’ll find, and a definition that has some spooky relevance to the 21st century in the West,” Zientek said.

Despite his growing popularity with the German people, Hitler was never voted into office. Paul von Hindenburg, a conservative politician and monarchist, remained president and strove to protect democracy as an elected official even though he did not believe in it.

“Hindenburg disagreed with Hitler’s rabble-rousing rhetoric and rightfully worried about mass violence in the streets should Nazis take power,” Zientek said. “It was an irony that this old conservative represented the final bastion of the democratic republic in Germany.”

Hitler reacted by threatening Hindenburg with direct opposition. Although they failed to win a majority, the Nazi party had won the largest number of seats in the Reichstag, the German parliament.

“The Reichstag was a complete disaster incapable of governing, and Hindenburg governed by bypassing it entirely and ruling through the president’s power to decree,” Zientek said. “He was desperate to restore the Reichstag to a functional government.”

In mid-November, Hitler received an offer to become vice-chancellor, which he rejected. He would only accept complete Nazi control of the government.

The current chancellor, Franz von Papen, convinced Hindenburg that they needed to enter a pact with Hitler, believing that they could exercise control and limit his power. Not wanting to struggle against his dysfunctional parliament anymore, Hindenburg allowed himself to be convinced that Hitler could be safely appointed chancellor.

“The final stage of this was not some brilliant takeover, as the Nazis later represented,” Zientek said. “Hitler lost the contest for governmental authority, [only being] offered governmental authority ex-post-facto. He was only given this authority because he had already lost it and his opponents thought him weak and powerless. They were wrong.”

In February 1933, Hitler announced his intentions to dissolve the Reichstag and rule Germany forever. By mid-March, 10,000 individuals were in concentration camps. Hitler used the Weimar Constitution to enact a permanent state of emergency, restricting personal freedoms. When Hindenburg died in 1934, Hitler passed another law that combined the chancellorship and presidency into one office, effectively establishing his dictatorship.

“In other words, the catastrophe happened very quickly,” Zientek said. “It took only a year for the Nazis to establish political power and intimidate the rest of society into acquiescence. When Hitler took power, ordinary Germans were enthusiastic. They believed that he would solve their problems. They did not quite grasp where they were. They did not grasp that their world was on a course to war, genocide and annihilation.”

Zientek made three points in the way of conclusion.

“First, Hitler was legitimately popular,” Zientek said. “He wasn’t hiding who he was. His message was public and his rise to power was not a case of pulling the wool. There’s this trope that the first victims of the Nazis were Germans — that’s one of the dumbest things I ever heard.”

Second, Hitler’s original grasping of power happened through entirely legal means.

“Hitler’s goal was to win control of the institutions of democratic government and then twist and pervert them so that the destruction of democracy would appear to be democratic,” Zientek said.

Lastly, Hitler’s rise to power was dependent on those in power willfully blinding themselves to the clear danger that Hitler posed to democratic government, failing to act in any meaningful way against the threat of fascism.

“Had von Papen and Hindenburg believed they would not be able to control Hitler, the entire history of the world would have been much better,” Zientek said. “It did not have been this way and it would not have been, if not for the myopia and blind optimism of the traditional conservatives in Germany. They, more than anyone else, are to blame for Hitler’s seizure of power— they simply gave it to him.”

After concluding his lecture, Zientek engaged in a short Q&A session and addressed similarities between Hitler’s rise to power and the United States’ current political circumstances.

“Who knows what the hell is happening?” Zientek said. “The days we’re living in right now, people are going to be talking about a thousand years from now — if there’s still people. We won’t know what will happen until 30 years from now.”

Zientek also found resonances in how left-wing German political parties failed to take action in the pivotal years following the Great Depression, leading to the eventual Nazi regime.

“The German Social Democrats thought the good years would last forever, and when the depression [of the 1930s] came, they couldn’t come up with a solution, not even a bad or fake one like the Nazis had,” Zientek said. “The failure of the centrist left to do anything is an interesting story, which has its parallels as well.”

Written by: Julie Huang — arts@theaggie.org

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to include photographs from the lecture, courtesy of UC Davis History Department faculty.