Will Sisyphus succeed in ending his story?

By ABHINAYA KASAGANI— akasagani@ucdavis.edu

Sisyphus is having trouble conceiving an ending for his latest story, unable to shirk the feeling that his current draft leaves something to be desired.

As a man once condemned to roll a boulder up a mountain for the rest of eternity, he finds himself stumped at the prospect of ending a short story for a class at university. He tries regardless, attempting to carry these words up a hill with immense intention and care: nothing.

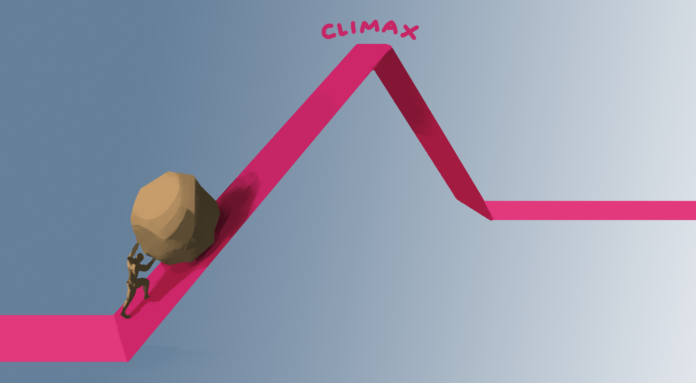

His professor suggested that he try to leverage the use of Freytag’s Pyramid — which essentially divides the structure of a basic story into categories of exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution — to do the job for him. Great: a second mountain to climb. Sisyphus is tired.

He goes to consult others on his story, and they tell him it reads wonderfully — that his exposition is solid, that he has a great narrative voice and that his story consists of phenomenal turns of phrases that are individuals in their own right. They also asked what the ending would be. To Sisyphus, this felt like a taunt — they are all privy to the fact that he is incapable of resolution, and so, the boulder of narrative structure rolls back down and out of reach. Maybe they chalked his dismissal from the mountain up to incompetence and not exoneration? He is too tired to prove any differently.

Sisyphus sits back down at his desk, writing and rewriting drafts that are stale, unintelligent and either too abrupt or tangential.

He considers tying up loose ends, then loses focus. Tying things up with a bow dilutes the piece, while not doing so cheapens it, leaving everything he means to say ambiguous and unclear. He considers the traditional approach, circling around Freytag’s Pyramid a few times, throwing several ideas against the mountainous structure and hoping one sticks.

Hours of modifying his story to fit another medium force him onto a road to nowhere — he tries making it a poem, a short film, an illustration, a comic and ultimately a song — and he is miserable by the end of this, pleading that he be sent back to the mountain and that a creative writing class is too exacting for his liking.

He sends an email to his professor, likening pushing a boulder up a mountain to being a writer. He admits to a directional change of his tendencies — what was once striving upward is now a downward spiral. School, he admits, requires from him the same energy and dedication as his previous punishment, but spreads him too thin and in too many directions. At least then, all he had to concern himself with was a singular boulder. Chasing a grade takes more from him than it gives.

His professor emails him back: Everything in the world is an uphill battle, simply try again.

So, he does. Attempt 15: He writes an ending that mirrors the beginning. Story of his life. One can only write what they know. Attempt 36: The climax precedes the falling action and is then succeeded by the exposition. This subversion makes the story illegible. Attempt 56: He debates the use of Artificial Intelligence and then is embarrassed by his desperation, deciding against it. Maybe he would prosper as a stonemason or something.

Attempt 542 ends up being another iteration of his inability to finish a story, or anything else for that matter. His story is set in Boulder, Colorado as a subtle nod to his decreed punishment. He is not fully sure if he is proud of his work, but one must imagine Sisyphus happy to have finally seen something through.

Sorry again if this is a cop-out of an ending. I, too, have trouble with the Sisyphean task of resolution.

Written by: Abhinaya Kasagani— akasagani@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: (This article is humor and/or satire, and its content is purely fictional. The story and the names of “sources” are fictionalized.)