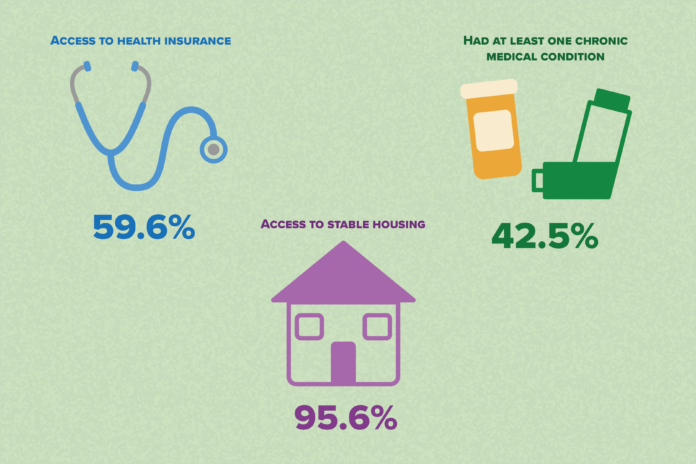

Of the 529 individuals detained by ICE that participated in the study, 42.5% had at least one chronic health condition and 20.9% experienced a disruption in their healthcare

According to a recent study by UC Davis, immigrants detained in the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facilities are at a greater risk of contracting COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions. Dr. Caitlin Patler, an assistant professor of sociology at UC Davis, was the lead author of the study alongside Altaf Saadi, a neurologist at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital.

The motivation behind the study was the death of Carlos Ernesto Escobar Mejia on May 6, 2020. He was the first person in ICE custody to die from COVID-19, according to Patler. ICE reported that 4,444 detainees out of 22,580 in their detention facilities were infected with COVID-19 between February 2020 and August 2020, according to the study.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there is no information available to the public on clinical characteristics that could assist in detecting the health conditions of the detainees or if they are more prone to contract COVID-19. To determine who will be most at risk, the researchers examined a systematic cross-sectional health survey from 2013-2014 of adult immigrants detained in California to collect information on any chronic conditions, lack of healthcare and sociodemographic characteristics that would cause major consequences when testing positive for COVID-19.

“Understanding detained immigrants’ health profiles is vital to decision-making on the part of policymakers, public health professionals, legal advocates and others seeking to stop the spread of COVID-19, reducing morbidity and mortality among detained immigrants and minimizing impact on local healthcare resources,” Patler said.

The results of the survey were that 42.5% of detained immigrants had at least one chronic health condition, 15.5% had multiple and 20.9% of the 529 detained experienced a disruption in their healthcare, according to Patler. This indicated that a large number of immigrants who were detained would be in danger of facing severe outcomes when exposed to the virus.

“I was alarmed to see the high prevalence of chronic health conditions in the study,” Palter said. “We know that prisons, jails and detention centers are bad for health. Our results, combined with that fact, raise serious questions about whether it is ethical or humane to detain people indefinitely under civil law.”

The survey also revealed that 95.6% of individuals in Patler’s study had access to stable housing in the U.S., which is critical for their chances to be released from detention centers. For immigrants that come to the U.S. without being detained by ICE, the health of their children is still affected. Erin Hamilton, an associate professor of sociology at UC Davis, studies immigrant health and commented on the differences in health between immigrants and U.S.-born citizens.

“So the big pattern of immigrant health that’s really interesting is immigrants on average in the U.S. tend to have better health outcomes than U.S.-born members of the same national background,” Hamilton said.

In her research on the U.S.-Mexico migration, there is a common pattern that children born in the U.S. often have worse health than their parents who were born in Mexico and migrated to the U.S. This has been seen in European, Caribbean and Asian immigrants as well and is often contradictory to popular belief because immigration is thought to be a difficult venture, according to Hamilton.

“Losing your comfort, language familiarity, networks, the place that you grew up… all of those things are really hard,” Hamilton said.

Despite that, Hamilton in her research continues to see worse health in the next generation of immigrants in comparison to their parents. One possible explanation for this is that individuals who decide to immigrate are different from those who do not. Immigration is very difficult because of all the costs involved and is something that people tend to do proactively in order to improve their lives, according to Hamilton. People who are willing to take a risk and face hardship are more likely to be more motivated, ambitious and hopeful, and these qualities may indicate that they are in good mental and physical health, according to Hamiliton.

“Immigration is not randomly sampling from the population in Mexico, it is selecting a particular group of people [who] tend to be healthy, and their children are not selected in the same way,” Hamilton said.

By the second generation of immigrants, the characteristics exhibited by their parents do not necessarily directly transfer. Instead, some children are motivated and some are not. Other factors in reduced health are the culture of the U.S. which includes fast food, smoking, drugs, lack of exercise and discrimiantion against immigrants, according to Hamilton. There is also the possibility that immigrants are comparing the U.S. to where they immigrated from and know they are improving their life, while their children do not have a similar comparison for the U.S.

While there is evidence of health differences between immigrants who are in detention centers and immigrants who are not, there is yet to be research done on how COVID-19 affects detained immigrants versus the children of immigrants. However, the primary concern is how ICE detention centers are jeopardizing the health of immigrants coming to the U.S., according to Palter.

“Our study makes clear how harmful detention can be for health and underscores [the] need to find alternatives to detention now, and keep it that way after the pandemic ends too,” Patler said.

Written by: Francheska Torres — science@theaggie.org