Researchers are attempting to use brain-computer interface technology to read and convert neurological signs

By BRANDON NGUYEN — science@theaggie.org

Anarthria is a severe motor speech condition that prevents an individual from entirely articulating speech, usually a result of a neurological injury or progressive disorder, such as a spinal cord injury or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Recently, UC Davis Health researchers have begun a pilot clinical study to develop neurological prostheses or devices that can restore speech and improve patients’ quality of life.

Joining BrainGate, UC Davis will collaborate with other academic institutions with the overarching goal of restoring neurological function for people with paralysis.

“The collaborative, diverse BrainGate team creates and tests the devices that are ushering in a new era of transformative neurotechnologies,” BrainGate’s website reads. “Using an array of micro-electrodes implanted into the brain, our pioneering research has shown that the neural signals associated with the intent to move a limb can be ‘decoded’ by a computer in real-time and used to operate external devices. This investigational system called BrainGate has allowed people with spinal cord injury, brainstem stroke and ALS to control a computer cursor simply by thinking about the movement of their own paralyzed hand and arm.”

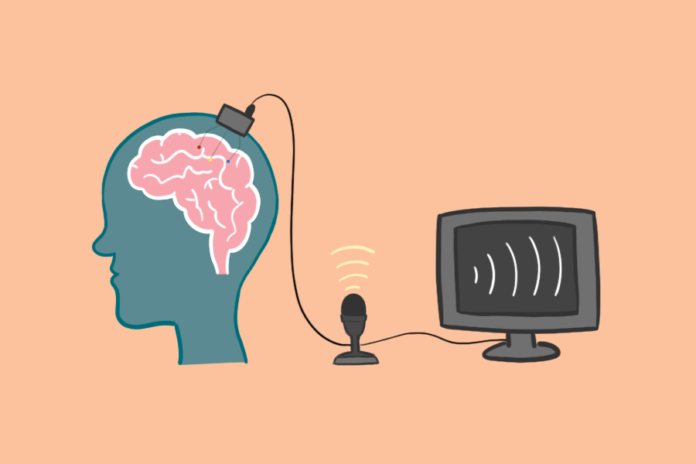

To restore speech, the researchers are testing a device called a brain-computer interface (BCI). Dr. Sergey Stavisky, a neuroscientist co-leading the study and co-director of the UC Davis Neuroprosthetics Lab, explains the function and purpose of a BCI.

“You can think of a BCI as a bypass of the damaged part of the nervous system,” Stavisky said. “The person is cognitively fully there, but those signals from their brain aren’t reaching their muscles in ALS or spinal cord injury, for example. If we know that the parts of the brain that would normally produce movement — speech, in our case — are working more or less normally, just not reaching the speech muscles, we can use a BCI to interpret the brain neural signals and translate them into speech through a computer.”

According to Stavisky, the idea is to place tiny electrodes in parts of the brain controlling speech and record the activity of a few hundred neurons. From there, the researchers can apply machine learning and other statistical signal processing techniques to interpret the activity and accurately output the intended speech through a computer.

Dr. David Brandman, a neurosurgeon serving as the site-responsible investigator for the study and co-director of the UC Davis Neuroprosthetics Lab, provided insight into the inspiration behind his pursuit of neuroprosthetic devices to restore function in patients suffering from paralysis.

“What we hope to do is restore naturalistic speech to people that are living with various [neurological conditions], and so the question is: what inspired me to do it?” Brandman said. “The answer to that is by meeting patients. I mentioned that I wear two hats, and the first that I wear is that of a surgeon, and I have met patients firsthand that want to interact with their environment. They live with diseases that prevent them from clearly speaking, and that they’re quite frustrated, and have difficulty communicating with existing assistive technologies that are slow and cumbersome. And so what really inspired me to pursue this line of research is recognizing that there are people in need of this technology.”

Currently, the pilot study is recruiting participants within three hours of driving distance of UC Davis Health. Ultimately, Stavisky and Brandman hope to offer patients a device that can improve their overall quality of life and allow them to speak to their loved ones comfortably again.

“I’d like to get to a point within the next decade where I’d be able to meet a patient and say, ‘Look, I’m sorry Mr. or Mrs. Smith that you’ve had a spinal cord injury. But your brain computer interface surgery scheduled for next week will get you feeding yourself a week afterwards,’” Brandman said.

Written by: Brandon Nguyen — science@theaggie.org