Suicide data can be essential information, but public universities aren’t required to collect by any state, federal bodies

This article is the first in a multi-part investigation by The California Aggie looking at suicide statistics in the UC system. As these statistics are not maintained by the UC Office of the President, The Aggie has compiled the previous decade’s worth of suicide statistics at each of the 10 UC campuses through public information requests.

Patti Pape lost her son Eric Pape in May 2017 when Eric, a student at UC Davis, died by suicide. Since then, Patti Pape has become an advocate for increased access to mental health resources, talking at churches and schools, attempting to influence public policy and speaking with local representatives.

Patti Pape was “horrified” to learn that the UC system has no official policy nor standard on collecting suicide data. There is also no systemwide policy on the collecting and reporting of this data nor is there a systemwide definition of suicide — information that was discovered through an independent investigation conducted by The California Aggie and disclosed by Andrew Gordon, a spokesperson for the UC Office of the President (UCOP).

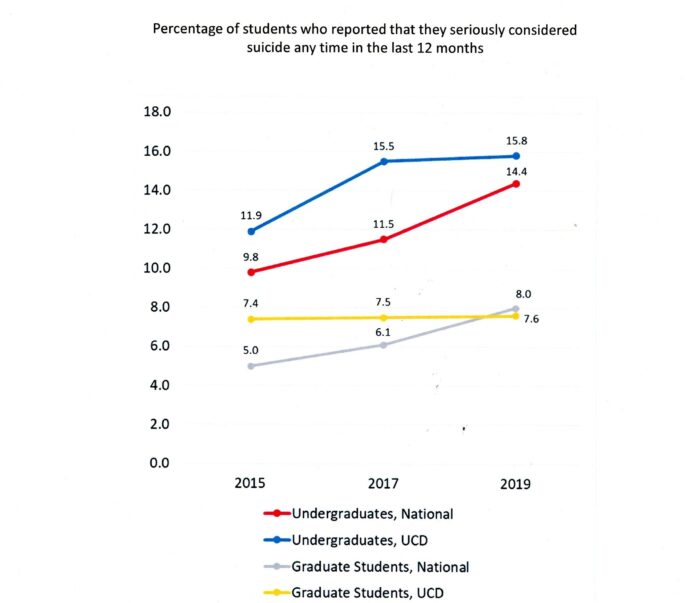

At UC Davis, 15.5% of undergraduate students had seriously considered suicide at any time over the last 12 months, according to a report from 2017. This rate is higher than the national average of 11.5% of undergraduates over the same period, according to a copy of a survey administered to UC Davis students last year as part of the American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment. In 2019, that number rose on campus to 15.8%, compared to 14.4% of undergraduates nationally.

UC Davis has had 20 suicides in the past decade — a number obtained by The Aggie through public records requests. This number was gathered by university officials using information from the UC Davis Police Department and the Office of the Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs, according to Julia Ann Easley, a spokesperson for UC Davis.

The number may not represent the actual number of student suicides at UC Davis over the previous decade. It is based upon deaths classified as a suicide by the county coroner who then notified UC Davis Student Affairs.

As Student Affairs does not keep a database of this information on hand, the number 20 was determined by university officials in order to complete The Aggie’s record request. When asked, officials from the university’s Student Health and Counseling Services said they had not previously heard this number, as it seems the data had not been put together in such a manner before now.

Additionally, UCOP does not have access to this information as it “does not maintain” suicide data, according to an official with UCOP’s public records office.

For Patti Pape, the lack of a systemwide standard for collecting this data “is not acceptable.”

“It doesn’t make sense that we have this national problem with suicides and the UC doesn’t feel they should be keeping statistics,” she said. “Not knowing where we’re going, where we came from and our history is just going to cause us to make the same mistakes over and over. Reform is necessary in order to keep our children healthy and alive. If you don’t know [your history,] you’re bound to stumble and have a crisis at some point.”

Why is it important to collect suicide data?

Experts say suicide data can be invaluable information for administrators. Dr. Jane Pearson, the National Institute of Mental Health’s (NIMH) special advisor to the director on suicide research, said in order “to change anything, you have to measure it.”

“For a lot of advocates who are very passionate about wanting to prevent suicide, if they’re not measuring it, you don’t know if all that energy and passion is going in the right place and it becomes a huge opportunity loss,” Pearson said. “It might make them feel better and it might create some awareness, but if it’s not really changing somebody’s trajectory, it’s hard to say whether that’s the best investment because we have limited resources and limited time to track that investment.”

When asked if she thought schools and universities should publicly publish suicide data, Pearson said ultimately, it’s up to the insitutions.

“You can’t force them,” she said. “If you’re looking for a school that uses data to do better, that’s a good thing.”

Mental Health America (MHA), the nation’s longest-standing mental health advocacy organization, strongly supports the collection of suicide data in a standardized way.

“If we collect good data about the ultimate stage four event — which is losing one’s life to a mental health condition, usually that’s gone untreated — we can do a much better job in the future of changing trajectories of lives before people get to these crises stages,” said Paul Gionfriddo, the president and CEO of MHA. “It starts from understanding what’s happening […] in order to be able to quantify the benefits we can get from intervening earlier.”

Universities aren’t required to keep suicide data. But should they?

There is no mandate, at either the federal or local level, requiring that public universities collect or report suicide data.

An official with the California Department of Public Health confirmed to The Aggie that the department does not require universities to report student suicides nor does the department collect this data from universities.

Given that there is no requirement for schools to report this data, there exists, then, a discussion over whether there is any incentive for universities and schools to collect the data in the first place — as well as whether there is an incentive for them to do the exact opposite and not collect the data at all.

“Many schools are tracking this data, they just have no intention of sharing them outside of the school,” said Dr. Victor Schwartz, the chief medical officer of The Jed Foundation, a non-profit organization focused on suicide prevention for the nation’s teenage and young adult population.

Schwartz, who formerly served as the medical director for New York University’s counseling services, continued to say that this data does, for the most part, exist, but it’s just not released to the public “because there’s no incentive.”

Most of the country’s large universities don’t track this data or, if they do, they do so in an inconsistent manner, according to a 2018 investigation done by the Associated Press.

The AP “asked the 100 largest U.S. public universities for annual suicide statistics and found that 46 currently track suicides, including 27 that have consistently done so since 2007. Of the 54 remaining schools, 43 said they don’t track suicides, nine could provide only limited data and didn’t answer questions about how consistently they tracked suicides, and two didn’t provide statistics.”

Based on the findings, the 100 universities examined by the AP were split into four categories: schools that don’t have statistics or don’t consistently collect them, schools that did not provide statistics, schools that provided limited data but did not answer questions about the consistency of their tracking and schools that currently keep statistics on student suicides.

Of the six UC campuses examined for the study, all six — UC Davis, Berkeley, Irvine, Los Angeles, San Diego and Santa Barbara — were placed in the fourth category: schools that do keep statistics.

Collin Binkley, a reporter from the AP who worked on the report, responded to a request sent by The Aggie asking how the publication decided to categorize UC Davis, among the other UCs listed, in this way. Binkley forwarded a completed CPRA request from the UC Davis public records office listing student suicides from 2006-2017 (there were a total of 25 deaths during this time period).

The responsive records Binkley received were formatted in a manner identical to the format of the responsive records received by The Aggie. In both instances, the responsive data was gathered from the UC Davis Police Department and the Office of the Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs.

“It is important to note that the Police Department only holds information on those cases to which they respond, and Student Affairs data is only noted once a death has been confirmed by a coroner,” the email sent to Binkley from the public records office stated.

By comparison, the eight California State University campuses examined for the study — Sacramento, San Luis Obispo, Pomona, Fullerton, Fresno, Los Angeles, Long Beach and Northridge — were placed in the first category: schools that don’t have statistics or don’t consistently collect them.

“We do not collect this type of data. No policy mandates it,” said Hazel Kelly, a representative from the CSU Chancellor’s Office, via email.

While there are no policies or requirements to report this data currently, Schwartz said there have been efforts on a state level to collect and publicly report this data, but there are also fears that there may be “perverse outcomes” from enforcing a mandate of this kind.

“If schools know that they’re going to have to report the number of suicides on campus, it may change the threshold for trying to force students who have suicidal ideations out of school with the thought that, “‘Well, if a death occurs off campus it’s a tragedy, but it’s not going to be on our statistics,’” Schwartz said. “Schools might wind up spending some time trying to game the system […] by making their statistics look as good as possible rather than doing what’s in the best interest of the student.”

Indeed, a class-action lawsuit filed in 2018 accused Stanford of discriminating against students struggling with their mental health by attempting to convince them to take a leave-of-absence and return home, rather than providing treatment through the university’s on-campus resources.

Schools and universities might fear they will be blamed for a suicide, Gionfriddo said, but this fear should not be a reason for inaction. When it comes to the collection of suicide data by institutions in a standardized format, Gionfriddo believes this is an obvious and necessary action.

“We need to press upon anybody who interacts with younger people [that] this data should be collected, it should be reported, [it] should be standardized and we shouldn’t be afraid to do that,” Gionfriddo said.

When asked whether she believes UCOP should implement a policy requiring that UC campuses collect and report this data, Margaret Walter, the executive director of UC Davis’ Student Health and Counseling Services, said she thinks about suicide data as parallel to the collection of data responsive to the Clery Act and the subsequent confusion this information sometimes causes when it is publicly released. The Clery Act is a federal statute requiring that colleges and public universities disclose certain campus crime statistics.

“The Clery data […] would never encompass all the issues of interpersonal violence that happen to our students in a given year [and] it only reports the numbers that were disclosed,” Walter said. “Having that number highlights the need to work on prevention and response to that issue, but it also creates a lot of confusion as parents look that number up when their children are applying for school and think that it means, ‘Oh, UC Davis and UCLA are different because these numbers are different.’ When really, you can’t assume that.”

Commenting on the university’s most recent release of Clery Act data, Sarah Meredith, director of the Center for Resources, Advocacy and Education, said in a previous article in The Aggie that statistics released through the act do not necessarily reflect the actual number of instances of a certain reportable event. For example, sexual assault numbers are not “necessarily reflective of the entire number of sexual assaults that occurred in a given year,” instead representing those campus community members who “felt they could disclose their experience to someone who happened to be a [mandated reporter].”

Walter said she believes tracking suicide data might “encourage more dialogue which could benefit prevention and response” which she sees as a positive, but because the data might always be “inadequate, it might also create confusion.”

Suicide rates in the U.S. are rising. What role can statistics play in prevention?

Suicide rates have gone up 30% in half of the states in the U.S. since 1999, but the changes in rates of suicide and suicidal ideation are perhaps the most pronounced among college-aged individuals.

Suicides among individuals aged 18 to 25 increased as much as 56% from 2008 to 2017, according to a study published in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology which looked at nearly 8 million survey responses.

Between 2008 and 2017, suicidal ideation rose by 68% among the same 18 to 25-year-old age group. Suicide attempts increased by 87% among the 20 to 21-year-old group and, among the 22 to 23-year old group, attempts rose by 108%, according to the study. Walter said the rising suicide rates align with higher incidents of anxiety and depression among the young-adult age group.

“Within the space of mental health, we are seeing students who are experiencing loneliness [and] anger at higher rates than ever before,” Walter said.

On a national scale, suicide rates have increased in nearly every state from 1999 to 2016 — California’s statistics, specifically, have seen an increase of 6-18% during this period, according to the Center for Disease Control. And the rates are steadily increasing: “The U.S. suicide rate increased on average by about 1% a year from 2000 through 2006 and by 2% a year from 2006 through 2016,” according to an article in Bloomberg.

Pearson said when she first started at NIMH, “we felt hopeful, and then slowly the rates have been going up.”

Internationally, other countries, including Japan, have seen suicide rates fall. In the late 1990s, Japan had some of the highest rates of suicide among industrialized countries, but around the 21st century, “Japanese citizens began to view suicide as a public health problem rather than as a personal problem to deal with in private,” according to an article from the American Psychological Association (APA).

As part of a plan to deal with rising rates of suicide, Japan mandated that detailed suicide statistics be released each month — “that step allowed suicide prevention resources to be matched to communities with the greatest needs,” the APA article states.

From the viewpoint of Schwartz, collecting suicide statistics is not the “end all be all,” as researchers have a general sense of the rate of suicide attempts and suicidal ideations on college campuses in the nation. In efforts to collect information, questions from universities should be framed from the viewpoint of: “What is it that would be helpful for the system to actually know that it doesn’t know now? And how might that better be gotten,” Schwartz said.

Generally speaking, there must be more done to help college-aged and high school-aged individuals, Gionfriddo said.

Gionfriddo was a former state legislator in Connecticut in the 1980s. He said that at that time, policymakers — himself included — were not doing enough to understand best practices for creating access to services and support systems. We’re still not doing enough, he said, but change can start with taking up the issue of reporting suicide statistics.

“If you don’t report adequately, if you don’t report properly, if you don’t report at all, it doesn’t change the fact of the death or the cause of the death, all it does is put our heads in the sand and minimize the value of that life and minimize the impact of that particular death on family, on friends, on peers, on the university community, on a broader community and on a state,” he said. “It should be a fairly easy thing to say, ‘Let’s just do this consistently, and let’s do it right.’”

The number for the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is (800) 273-8255.

Written by: Hannah Holzer — campus@theaggie.org