Six recommendations to expand your list of favorite female authors across the world

How many languages do you know? For most Americans, the answer is one.

This means that the majority of U.S. residents can only engage with literary works printed in English. Only 3% of the books published in the U.S. each year are works translated from another language — limiting a reader’s chance to engage with literary perspectives outside the Anglophone world.

Of that small percentage, even a smaller portion of translated authors are women. Three Percent, a web-based project formed at University of Rochester, tracks this gender disparity and further literary translation data within the U.S.

Since 2008, Three Percent has shared statistics detailing not only how much translated literature is hitting the market, but who it’s written by. Until 2013, the number of women in translation was comparatively low to that of men, representing about 26% of all works. Since then, the numbers have increased, reaching 47% in 2022.

This increase is attributed by Three Percent to projects like Women in Translation (WIT) Month — but you don’t have to wait until August to start expanding your reading horizons. These six works of translated fiction hope to inspire an international exploration of a forever-growing amount of international women’s literature; and they’re all available through the Yolo County Library.

“Fair Play” by Tove Jansson, translated from Swedish by Thomas Teal (1989)

Most well-known for her creation of the Moomins, Tove Jansson is one of Finland’s most translated writers, belonging to the country’s Swedish speaking minority. Suitable for the quiet and cold winter days, “Fair Play” stitches together vignettes from the lives of aging couple Jonna and Mari. Living in apartments connected through an attic corridor, the two creatives coexist in a comfortable routine brought on by many decades of union, drawing heavily from Jansson’s own life with her partner, respected Finnish Artist Tuulikki Pietilä.

The novel shows Jonna and Mari as they pursue creative endeavors, travel and banter no matter the occasion. Their simple happenings create an ideal environment for contemplating and slowing down to enjoy moments of contentment.

“The Last One” by Fatima Daas, translated from French by Lara Vergnaud (2020)

Set in a Paris suburb, this autobiographical novel reveals — through short snapshots — the life of the youngest daughter in a family of Algerian immigrants. The narrator introduces herself at the start of every chapter as she struggles to define herself within society, frequently troubled as she finds the different priorities in her life — family, school, religion, love — at odds with one another. She juggles being unsure of the life she wants to lead while trying to connect with distant parents and fostering a good image for her family in Algeria. Tackling issues of diasporic experience and the shakiness of young adulthood, “The Last One” is a story that moves from one subject to another in rapid succession to paint the complexities of life.

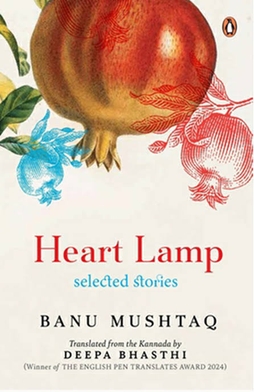

“Heart Lamp” by Banu Mushtaq, translated from Kannada by Deepa Bhasthi (2025)

The winner of the 2025 International Booker Prize, Banu Mushtaq’s short story collection explores the lives of Muslim women in Southern India. Translated from Kannada, the collection maintains the specificity of its native language rather than simplifying it for an English reader, giving a richer sense of the communities the stories are set in. The stories are often concerned with the detrimental impact of patriarchal structures and the way they interact with faith and women’s fortitude. In the title story, for example, a woman plans to self-immolate after discovering her husband plans to take a second wife to cover up an affair. Balancing emotional intensity with wit, this collection is well-deserving of its acclaim.

“Taiwan Travelogue” by Yáng Shuāng-zǐ, translated from Mandarin Chinese by Lin King (2020)

The translation of this book into English added an extra layer onto the already complex presentation of the story, perfect for fans of a nesting doll narrative. While “Taiwan Travelogue” is a complete work of fiction, the novel is introduced as a lost 1930s manuscript by a young Japanese novelist, which has been translated into a “New Mandarin Chinese Edition.”

Detailing the novelist’s travels in Taiwan — at that time, a Japanese colony — “Taiwan Travelogue” closely examines her relationship with her Taiwanese translator, exploring themes of colonialism and power dynamics while framing the chapters around regional foods.

The manuscript is sandwiched by fake introductions and afterwords by scholars, family members of the characters and Yáng Shuāng-zǐ pretending to be the translator of the original edition. Told by a narrator both insightful and unaware, “Taiwan Travelogue” makes for a wonderful interrogation of the meta relationship between translation and the context it’s used in.

“Life Ceremony” by Sayaka Murata, translated from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori (2019)

By starting with a story about a society that values human body parts as the preferred material for everyday objects, Japanese Writer Sayaka Murata makes you very aware of what kind of collection you’re getting into. Full of stories that veer into the strange and unsettling, “Life Ceremony” questions the things considered inherent and unshakeable by leaning into the off-kilter. Murata’s straight-forward prose underscores the initial reaction to the stories as she challenges cultural taboos. The collection is a shocking ride that leaves you wondering about what norms you let control your life, being drawn again and again to the strange conclusions of the stories.

“The Employees” by Olga Ravn, translated from Danish by Martin Aitken (2018)

Subtitled “A workplace novel of the 22nd century,” this book presents a human resources (HR) investigation for the stars. Composed of a series of statements from workers on the spacecraft Six-Thousand Ship in order for the corporation directing the ship to determine workplace efficiency, what follows is the description of a closed environment getting more out of corporate hands. The ship is staffed by both human and humanoids — replicable inventions programmed to work only on board — who chronicle daily tasks and quickly devolve into increasingly strange behavior associated with the mysterious objects brought on the ship while exploring deep space. The statements are largely anonymous, sometimes out of order and full of redacted information, blurring the lines between human and programming as their statements become harder to tell apart. Capturing the sterile and isolating corporate workplace, this book is perfectly timed to consider the future of automation and company control in our current society.

Reading literature in translation may open your mind to new perspectives, whether through experiencing other cultures, exploring ambitious science fiction worlds or observing innovative ways of structuring a narrative. If you’re seeking to broaden your reading this year, these recommendations offer a unique place to begin.

Written by: Hannah Osborn— arts@theaggie.org